Monday, April 26, 2010

The Rise of Art World 2.0

by Ted Mooney

by Ted Mooney

Two years into what we seem to have agreed, in full supine position, to call the Great Recession, it is clear to almost everyone that something has indeed taken its course, and that in many respected fields of endeavor things will never be the same. As someone who has pursued with equal commitment two parallel careers throughout my life─one in the art world (as an editor, a writer, and now as an educator at Yale’s graduate School of Art), and another in the literary world (as a novelist, essayist, and short-story writer)─I am struck, if not exactly surprised, by the similarity of the changes the recent financial meltdown has wrought on both fields, changes long in development but only now openly validated. I say changes, but in fact they are paradigm shifts, since both the art and literary worlds are undergoing transformations that will prove to be game-changingly radical. This much is certain: what was before, will be no more. The sooner we realize this, the more options we will have in the future.

Talking about this paradigm shift in regard to the art world is strangely difficult, for the very reason that the term “art world,” so casually bandied about by almost everyone, is most often used to refer to something that is at best a suspiciously convenient myth. No such all-encompassing art “world” exists. Most likely it is this misuse of the word “world” that has left the term “art world” itself open to such a wide range of misunderstandings. But in fact “art world” does have a very specific meaning, one quite different from the fuzzy globalist entity most often summoned up by those who use it so indiscriminately. Simply put, the art world consists of all those involved in the commission, creation, valuation, promotion, presentation, sale, criticism, documentation, and preservation of art. And with that established, many other matters grow a good deal clearer.

While we have always had artists in the U.S., for example, the American art world─one including all the elements listed above─is a much more recent development. Borrowing from the nomenclature of the software industry, I will call the U.S. art world’s earliest incarnation Art World 1.0 and locate its emergence somewhere in the mid- to late 1930s, when a number of forces came together in New York to create it. These forces included the sudden arrival here of European artists fleeing the onset of World War II; the convergence in New York of other European emigré artists who had moved to the U.S. much earlier but now joined their fellow exiles in the nascent art capital; and a similar movement of American artists away from the heartland to the growing artistic ferment in the East. In addition to these historical migrations, the federal Works Progress Administration, at that time the largest employer in the post-Depression U.S., provided substantial support for the arts, allowing, for example, Willem de Kooning (who had reached New York in 1927) to earn more than three times the salary of a typical Macy’s employee of the same period, all while painting public art works for which he was paid with federal dollars. What’s more, several other elements of the art world as I have defined it were already in place: among them Alfred Barr’s then artist-friendly MOMA, such prescient commissioners of art work as Peggy Guggenheim, a handful of important galleries, soon followed by art and culture periodicals like In the Tiger’s Eye, and View—enough of the necessary elements, anyway, to give critical mass to the first genuine U.S. art world.

Money was certainly made within this self-contained enclave, but not very much, and the institutions and collectors who acquired the art works emerging from these artists’ studios did so mainly out of their acute awareness that this was a historic moment, unprecedented in the U.S. Few if any of these collectors imagined that the works they were buying would in a very short time increase astronomically in monetary value, so speculation was a negligible factor. It was sufficient that enough money be circulated through the art scene to keep the artists alive and productive. And with only short periods of stasis, indirection or revolt, the New York art world evolved from that first iteration into what we know today, its characteristic elements continuously shifting in relative importance as the art eco-system grew in volume and self-confidence.

I will leave the reader to decide when exactly the art world’s incremental upgrades occurred─when 1.0 became 1.1, and so on─confining myself instead to a few obviously watershed moments. By the late 1940s and early ’50s, the Abstract Expressionists had became pop-cultural stars whom the average American saw in equal measure as perplexing oddities (“My kid could’ve done that”) and gratifying emblems of postwar American dominance (“Take that, Europe”). Indeed, they became such accepted emblems of a newly prosperous U.S. that the federal government (in the form of the U.S. Information Agency, now known to have functioned abroad as a propaganda arm of the C.I.A.) sent their works on extended worldwide tour as a potent psychological asset in waging the Cold War.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s another major change occurred, as the soul-baring feats of the Abstract Expressionists and their progeny gave way to the cool ironies of artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and all those other artists so hastily lumped together by the media under the rubric of Pop art. I’ll call this moment the arrival of Art World 1.5, since, in my opinion, it brought us halfway to where we are now. With it came a shift in sensibility that suggested a new detachment of artist from artwork, one that allowed the expansion into that same ironic distance of the other art-world elements, those that till now had usually played a secondary role. The valuation, promotion, presentation, and sale of art began to take on more weight, and the normative practices in these areas showed signs of changing and evolving in ways till then unforeseeable.

Simultaneously, a new breed of collector emerged, exemplified by people like Robert Scull, who made his fortune from a Manhattan taxi fleet inherited from his father-in-law, had no real background in art and simply bought what he liked—in quantity. Pricing became more aggressive, promotion took on a glamour of its own, and the social aspect of the art world veered increasingly toward spectacle. Not only did this period mark the peak of postwar prosperity in this country, but it was also a genuinely thrilling time for U.S. art, one as innovative in its way as that ushered in by the Abstract Expressionists. What’s more─and here Warhol is the obvious example─the subject of much of this art was commerce, money, glamour, and popular culture. So for the first time the economic elements of the art world were unapologetically accorded billing equal to the art and the artists themselves. And with this acceptance, the ethos that has brought us to our present pass was unequivocally established.

To be sure, there were those who worked in explicit rebellion against the overall commercial trend of the art world─the Conceptualists, the Earthwork artists, performance artists, and others─many of whom produced art that, though intended in part to be “uncollectable,” must be accounted major work by any standards. But the expansion and increasing commercialization of the art world─punctuated by the booms and busts intrinsic to any market-linked community─continued apace. Among the innovations that contributed to the art world’s rapid development from the 1960s on were the decreasing cost and consequent proliferation of color reproductions in art magazines, the rise of graduate art-school programs (which implicitly presented art as a solid career path, comparable to, say, dentistry, in the security it offered), the increasing acceptance of the nakedly commercial art fair as a legitimate forum for presenting art, the ascension of the artist super-stars of the 1980s, the exploding resale market for contemporary art at venerable auction houses, the construction boom for contemporary art museums as they became more and more widely perceived as tourist magnets that no respectable mid-sized municipality could do without, and, finally, the vastly accelerated exchange of ideas and images that the Internet allowed. By the time the Museum of Modern Art reopened its doors after its lavish renovations of 2002-04, it is safe to say that Art World 1.9 had reached its apotheosis and begun its ongoing decline. Art World 2.0, a complete reset of the original, with consequences only beginning to be known, was taking shape.

Why do I locate this changeover at that moment? It’s tempting to point to the example of the newly expanded MOMA, a grotesquely misconceived distortion of its former self. As far back as the 1970s there had been talk, both within the museum and outside it, of declaring MOMA a historical museum, a museum precisely of modern art, which is generally seen as having come to a triumphant end with Minimalism. Watching MOMA continue to show contemporary art in its ostentatiously corporate, quintessentially modernist quarters seems to many like watching a 75-year-old man (the Modern opened in 1929, the very year the Great Depression began) attempt a kickflip indy at the local skateboarding park─a sight unseemly at best, but in any case a clear indication that all self-awareness has long since departed the scene. That may sound like a cheap shot, but within it lies a kernel of ineradicable truth. Every three generations (and I’m using “generation” to mean the traditional 25 years, not the five to ten years implied by advertisements and over-wrought publicists) the living memory of how the world was “back then,” what its inhabitants at that time aspired to and how they went about getting it, begins to die off. The number of eyewitnesses rapidly diminishes until we become reliant on second-hand accounts, self-serving memoirs, and conflicting rumor to summon up a vision of the original. Soon nothing can be verified with certainty, the “real” past is lost, and it can only carry on as a simulacrum of itself. Not until then, paradoxically, can the genuinely new, brought into being of its own necessity, be born and thrive on its own terms. Now, for the American art world, that time is upon us.

While it must be emphasized that Art World 2.0 remains in its earliest stage of development, it currently seems characterized by a studious rejection, quiet but steely, of the corporatization of art so enthusiastically and profitably pursued during the Art World 1.9 years. Among my grad students and many of their confreres in their mid-thirties or younger, there is a strong preference for art that in one way or another emphasizes “secrecy,” subversion, withholding, ephemerality, word-of-mouth invitation, sub-visible presence, intimate one-on-one interaction between artist and “viewer” and strong artist-to-artist dialogue. Where there’s institutional critique (and there’s a lot of it) it’s unlikely to be cast in the flamboyantly confrontational style of, say, Hans Haacke. Instead it might take place within a chosen “major New York museum”─the default term proposed by some leading museums after the almost Talmudic deliberations of their legal departments─among a group of invited participants, the results to be documented, if at all, by the museum’s security cameras. (It seems significant in itself that “surveillance”—both inside museums and elsewhere--is a hot topic among Art World 2.0 artists, who are acutely aware of the demise of privacy and ingenious in their attempts to resuscitate it.)

In addition, widespread revelations about the recent criminal activities of respected banks and international corporations, crimes that have almost without exception gone unpunished, have made virtually all corporate practice suspect to a sizable proportion of Americans, and to many of the Art World 2.0 artists it is, at least for now, anathema. As they attempt to reclaim for artists the freedom and respect once naturally accorded the best art work, independent of the by-now customary financial indices and career-path signposts, they have begun to seek alternative ways of structuring their art world. And they have learned how to adapt for their own purposes the near-universal corporate response to the recent financial meltdown; they have developed ways to eliminate (or at least minimize) the middlemen.

In addition, widespread revelations about the recent criminal activities of respected banks and international corporations, crimes that have almost without exception gone unpunished, have made virtually all corporate practice suspect to a sizable proportion of Americans, and to many of the Art World 2.0 artists it is, at least for now, anathema. As they attempt to reclaim for artists the freedom and respect once naturally accorded the best art work, independent of the by-now customary financial indices and career-path signposts, they have begun to seek alternative ways of structuring their art world. And they have learned how to adapt for their own purposes the near-universal corporate response to the recent financial meltdown; they have developed ways to eliminate (or at least minimize) the middlemen.

This strategy is only possible because the old Art World, as well as modernism and the various morbid offshoots that followed its demise, is dead to them. They accept this as a fact, but don’t dwell on it, since the corporatization that marked Art World 1.9’s endgame is of little relevance to them, except as a warning. What most concerns these emerging Art World 2.0 artists from a practical standpoint is regaining control of how their work is presented and, given the ever-greater importance of the Internet, how the reproduced images of that work are disseminated. To those ends, many prefer to avoid long-term gallery affiliation altogether, seeking instead the most suitable venue for each new project as it is completed. By stringing together a series of one-shot appearances in places of their own choosing, they are better able to maximize their freedom and shape their work’s development. This may be seen as a direct response to the financial hysteria of the Art World 1.9 years, which led to the virtual extinction (though always with magnificent exceptions) of long-term, even life-long relationships between gallery and artist. In times not nearly as distant as they now seem, galleries saw it as their role to nurture and develop their artists, eventually to arrive at a mutually beneficial outcome through patience and hard work. But the frenetic financial pace of Art World 1.9─whereby new artists would typically be given two or three shows to demonstrate their financial viability before, if their work failed to sell impressively, being summarily dropped─did away with these nurturing relationships, and Art World 2.0 artists have quite sensibly concluded that their best option is to nurture themselves. This shift in thinking explains the primary emphasis Art World 2.0 artists place on building and maintaining their connections with other artists; they want a mutual support structure that they can depend on. Not only does this preference mirror their widely shared interest in reconnecting with their audience personally, in many cases on an intimate one-to-one basis, but underscores their deep-seated resistance to any form of outside control whatsoever, from any quarter. This insistence by Art World 2.0 artists on setting their own terms is yet another bit of bad news for galleries, who have already begun to see their high-end artists’ new work bypass them altogether, going straight from studio to auction house, where a successful sale can establish an artist’s financial worth much more effectively than a sold-out gallery show, which is by nature not at all transparent. The gallery dealer can and does make use of a whole range of tricks to achieve the desired public perception of a given show’s outcome, including under-the-table discounts, non-existent waiting lists for a particular artist’s work, failure to disclose the prices at which works really sold, and many other sleights of hand. At auction, the process is far more transparent: a work is sold to the highest bidder, conferring on the artist a more certain status and financial validation. Foreign collectors, especially from emerging markets such as Asia, are far more comfortable buying the work of an artist with whom they may not be familiar if that artist has already received the imprimatur of a respected auction house.

Obviously, auction houses are unlikely to accept a consignment from an untested artist, and that fact, along with the innate predisposition of Art World 2.0 artists to avoid entangling commercial alliances, assures that there will be many more artist-organized shows in the future. This polarization of sales venues corresponds, interestingly enough, to the drastically increased concentration of U.S. wealth into far fewer hands, beginning with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 and grossly accelerated during the Bush years. I have heard more than a few highly informed art-world players speculate pessimistically about the continued viability of art galleries in Art World 2.0. Personally, I think this is more a form of complaint than prognostication, but the possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand. At the very least it is a recognition, however indirect, that the reset implicit in the arrival of Art World 2.0 has already occurred.

What direction Art World 2.0 will eventually take cannot, of course, be known at this early date, but its initial aspirations are clear. Precisely because the monetary valuation of art, while based on some established indices, is at base irrational and subjective to the point of arbitrariness, the artist who is alert to these matters can work with a freedom unavailable to virtually all other workers in all other professions. This freedom was highly valued in the early stages of Art World 1.0─not only by artists but also by those composing the other necessary elements of the art world eco-system. Somewhere along the way, however, that freedom was lost to many artists as the art-world “support system” arrogated to itself more and more power, which came to influence artists themselves to an equally inflated degree. Those days may not be entirely over, but Art World 2.0 has arrived with the express intention of reclaiming its freedom and resisting outside influences, especially institutional ones, with all the energy and inventiveness its members can bring to bear.

They have already dismissed any notion of a master scenario for art’s development, simply by virtue of their arrival. They have the tools and weapons to take back their freedom, with its mix of blessings. Now we will see if they have the will.

Copyright © 2010 by Ted Mooney

Author: Ted Mooney was a senior editor at Art in America magazine for more than 30 years and now teaches a graduate seminar at Yale University’s School of Art. He is also the author of three award-winning novels, as well a number of essays and shorter works of fiction. His most recent novel, to be published by Alfred A. Knopf on May 11, 2010, is titled The Same River Twice. A video trailer for this book was created in collaboration with new-media artist John Gara and can be found at http://tiny.cc/TSRT-video .

Thursday, March 25, 2010

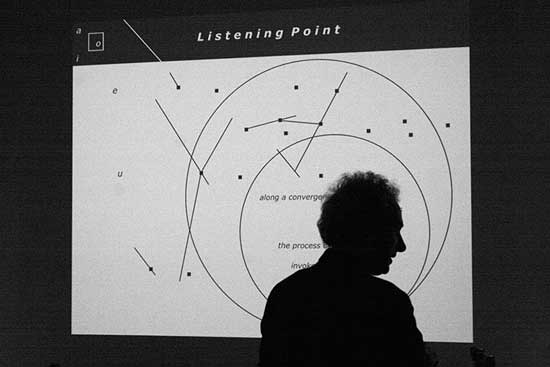

Mark Bloch at Emily Harvey Foundation

New York's SoHo, 03-25-10

The Art of Storàge

by Mark Bloch

More on The Art of Storage (.pdf)

The Art of Storage was recently seen as part of Mark Bloch's one man show "Secrets of the Ancient 20th Century Gamers" at Emily Harvey Foundation in NYC March 18 through April 2.

New York's SoHo, 03-25-10

correspondence: in the Artists' Voice

photography: Tom Warren for Mark Bloch

at Emily Harvey Foundation

photography: Tom Warren for Mark Bloch

at Emily Harvey Foundation

The Art of Storàge

by Mark Bloch

Storàge is a new art form for our times in which artists will prevent at all costs, their work from seeing the light of day. Artists must conceal what they do, make sure no one finds out that they are brilliant. If an artist must show someone something they have created, they should show another artist so as not to upset the art markets. Other artists do not really count as human beings so there really is no harm in telling them. That is how art continues to thrive. Artists are sequestered from the rest of humanity. But one should proceed with caution because occasionally artists know actual people and the news of what kind of work the artists are producing must not spread to civilians.

Storàge is an art form like many others: collàge, assemblàge, frottàge. The accent is on the second syllable. The emphasis is on the storing of important information and objects--preferably one of a kind objects, although the storing of multiples is also encouraged--until a great deal of time has passed and the ideas and images contained therein, hidden from public view, have been discovered and explored by other, less talented individuals. This is bound to happen while the work is rotting under lock and key, no matter how advanced the work. Even the most vanguard artist will be unable to stave off the advancing future which will soon provide the unique conditions necessary for the artist’s work to be removed from Storàge without consequence.

Once a work of art has been rendered culturally feckless, Storàge is no longer necessary. The work can now be trotted out into the marketplace where it will no doubt have to endure other types of packaging, wrapping and covering which are part of the Storàge process when enacted by a Storàgist but in these new contexts the accent in Storàge is removed and it becomes simply storage in which excessive packaging and hygienic germ free protection is always considered good for business. Of course any work of art or other consumer item, no matter how processed and "valuable," always remains in danger of being placed on dusty shelves in the forgotten back rooms of galleries or museums by art professionals. This is where the nuances of Storàge and storage are revealed--for it is these very art professionals who are uniquely qualified to determine whether or not an artist’s work is any good. During the interim period when the artists are left trying to make this crucial decision for themselves, their work must be safely hidden from view while these art professionals are courted at the artist’s expense without causing too much of a fuss, for it is the artist’s passion that must also remain in the limbo of Storàge, not just their output.

Sometimes fear of the art professionals will cause an insecure artist, one prone to alarmism and in constant dread of being accused of being labeled an exhibitionist, to send works into hiding early, thus risking beginning their career as a Storàge Artist prematurely. But there is nothing to be alarmed about here. Fears about these types of fear are only a waste of time. Any uncertainty at all must always be acted on immediately. To err on the side of invisibility is never a mistake. If an artist has any doubts at all about the worthiness of what has been created, they should simply place the work in a secure area, free from intellectually curious intruders where no one can see it. In fact experience has shown that no work is too ripe to entertain misgivings about its readiness for public consumption. Any suspicions at all should be indulged whole-heartedly and enthusiastically by the Storàge Artist.

Mark Bloch

More on The Art of Storage (.pdf)

The Art of Storage was recently seen as part of Mark Bloch's one man show "Secrets of the Ancient 20th Century Gamers" at Emily Harvey Foundation in NYC March 18 through April 2.

Wednesday, March 10, 2010

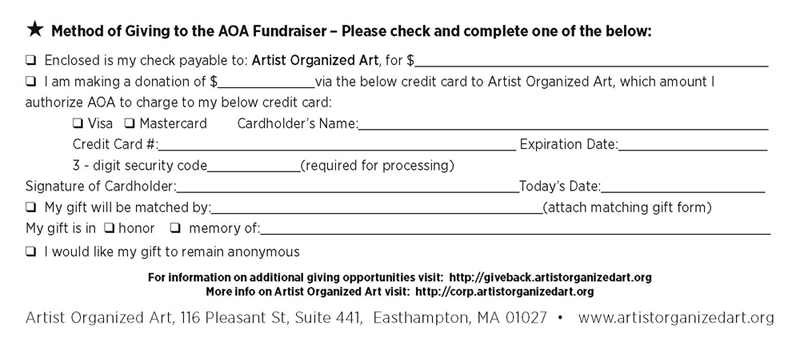

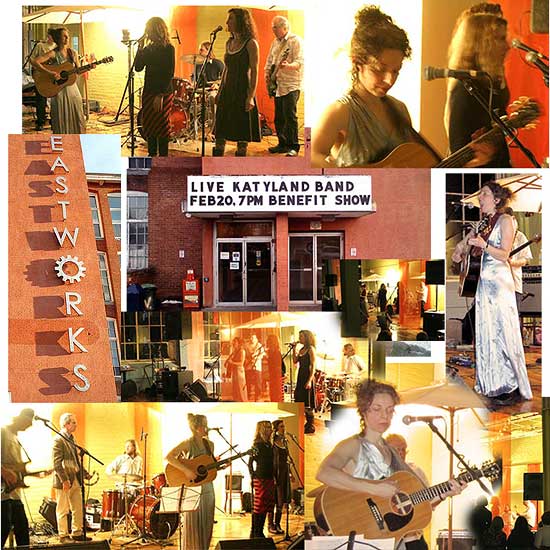

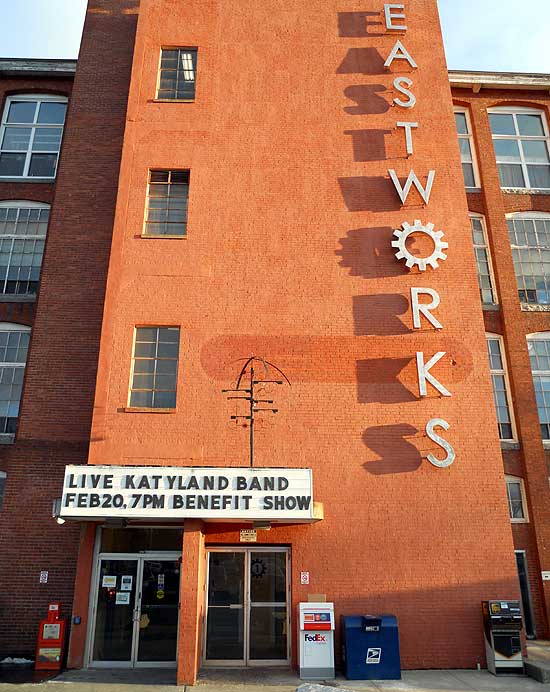

NEW WORKS • NEW VIEWS • NEW MINDS: Stage One: KATYLAND live at Artist Organized Art Benefit Launch

by Jessica Higgins and Erika Knerr

photography: Denis Luzuriaga

photography: Denis Luzuriaga

Participating artists: Aimee Xenou, Alicia Renadette, Andy Laties, Andrew Greto, Ann Lewis, Barbara Neulinger, Beth Lawrence, Carl Caivano, Christin Couture, Christine Tarantino, Christopher Blair, Dave Gloman, Dean Nimmer, John Landino, Denis Luzuriaga, Dwight Pogue, Erika Knerr, Fletcher Smith, Jessica Higgins, John Romanski, Joshua Selman, Kathleen Trestka, Katie Richardson, Katy Schneider, Laurie Goddard, Maggie Nowinski, Matt Anderson, Matt Anderson, Nancy Natale, Ninette Rothmüller, Pablo Yglesias, Rosa Guerra, Sarah Valeri, Sue Katz, Susannah Auferoth, Tracey Physioc Brockett, William Hosie, Luzuriaga video includes Ursonate Urchestra

February 20th was an auspicious date for the arts community! That Saturday night, was the first of three parties to benefit Artist Organized Art in which A.O.A. threw a community outreach event, arts network builder, exhibition, performance…did I forget to say fundraiser?

Northampton's Katy Schneider, a guitarist, singer, songwriter and painter, accompanied by Julie Starr and Caitlin Bosco on back up vocals, Jason Smith on drums and Bruce Mandaro on guitar and mandolin. http://www.myspace.com/katyschneider. Also see Katy's work at www.katyschneider.com

The event featured large projected images by local artists of the Pioneer Valley in Massachusetts and hard and soft indie music by Katyland along with some great cover songs, a regional progressive music favorite.

Denis Luzuriaga, a painter and video artist, compiled the projected images: in the dead of winter the crowd was treated to a colorful array of visual artworks, documents and pleasantly dated black and white photos of beach scenes.

The overall effect; "a swirling sound stretched out on the night with projections of art interfacing the viewers” Jessica Higgins

Each element of the event reflected a key component of the AOA mission to support creative independence in the form of self-supporting and self-generating exhibitions through artist organized media, events and cultural education.

The festivities took place at Eastworks a converted warehouse on the river at 116 Pleasant Street in Easthampton. Artists of all kinds and their allies came from neighboring towns as well as the studio and residential community of Eastworks, a loft building community founded by Will Bundy.

The social and experimental quality of the event recalled important artist communities associated with the avant-garde: Black Mountain College during the 1940s and 1950s, the Village and SoHo in the 1960s and 1970s, and California in the 1970s and 1980s. Why not Massachusetts as an internet hub brought together by AOA in the 2010s?

The event represents a significant group effort organized by artists: Susannah Auferoth, Jessica Higgins, Erika Knerr (also representing New Observations, the seminal New York arts magazine that was recently acquired by AOA), Denis Luzuriaga and Joshua Selman. Artist Organized Art is working to improve the quality of life through community culture.

The event isn’t over yet. If you were there and have pictures of the event, send them in to be a part of the record! If the event sounds like fun and you’re bummed you missed it, keep your eyes out for more. AOA is ever eventful.

The success of A.O.A. comes from community support (cultural, logistical and financial), which means everyone is invited to be apart of it, enriching our world by organizing its culture as artists. Benefit parties for Stage Two and Stage Three will be forthcoming.

Hannah Higgins a Professor of Art History at University Illinois, in Chicago working in DC this year at the Phillips Collection comments on the Artist Organized Art Facebook page: "Fan-freakin'-tastic! I want one in DC!" (http://www.facebook.com/pages/Artist-Organized-Art/52223923322)

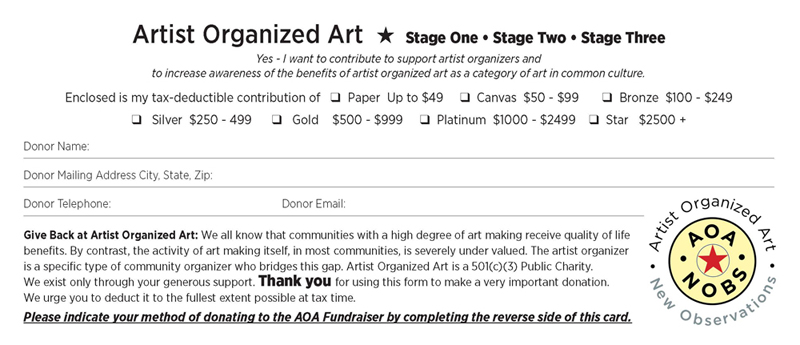

If you'd like to contribute to Artist Organized Art visit: http://giveback.artistorganizedart.org

Or print out the form below and mail it to us with your kind donation.

Or print out the form below and mail it to us with your kind donation.

Tuesday, January 26, 2010

FREESPACE IN THE CITY OF LIGHTS

Freespace Exhibition and Performances

59 Rivoli Aftersquat, Paris, December '09

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes

Building: 19 rue des Frigos 4 underground train tunnels approximately 1000 sq feet each and a garden

Established: 1998

Owner: former owner was SNCF then, le Réseau Ferré and then City of Paris since 2003

Regulated: 2000

Purpose: 'We decide to create a cultural association (and a garden) to rule the place. First to show our work, then the one from friends...'

Website: http://lesvoutes.org http://les-frigos.com

Les Voutes Artistic directors: Bruno Herlin and Pierre Wayser

Contract terms:

We do not receive any kind of funds or money !

We do not ask for money !

We do not want their money !

We do not have to say "thanks"!!

We just use some differents networks of international artists and share the expenses.'

Information provided by Pierre Wayser

59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivioli Aftersquat

Building: 59 rivoli, 6 stories, plus storefront gallery

Squat established: 1999

Owner: Bank of Lyon and then bought by the City of Paris

Expulsion by court of law: 2000

Regulated: 2001 (renovated and closed during 2006-2009)

Purpose: open studios to public everyday (except Monday) exibition space, artist studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 core members, around 30 artists working in building

Website: http://www.59rivoli.org

Contract terms: all artists are door greeters for 1 hour /week, each artist pays $160 for utility bills, building closes at 8pm

Information provided by: Swiss Morrocan

La Générale, Sévres

La Générale, Sévres

Building: original building on rue du Général Lasalle Paris Belleville new location: 60,000 square foot

Squat: established in 2005

Owner: National Education Ministry

Expulsion by court of law: 2006

Regulated: 2007 relocation to Sévres

Purpose: exibition spaces, wood and metal workshops, photographic studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 official members

Website: http://www.la-g.org

Art Residency directors: Sylvain Gelinotte and Jerome Guige

La Générale profile: Painters,VJs, scupltors, conceptual artists, performers, photographers, musicians, video artists, poets, drawers, young or older (mostly in the 30s), french and foreigner nationals (mostly are french speakers), somewhat famous and also perfectly unknown.

Contract terms: With the Regional Minister of Cultural Affairs (DRAC): 'they pay the rent and we run the space for the benefit of our work and visiting artists. Using the space to run a company or renting it forbidden'

Association Rules: $70 per month membership fee to pay for power, internet connection and the insurance that covers everyone

Information provided by: Jerome Guige

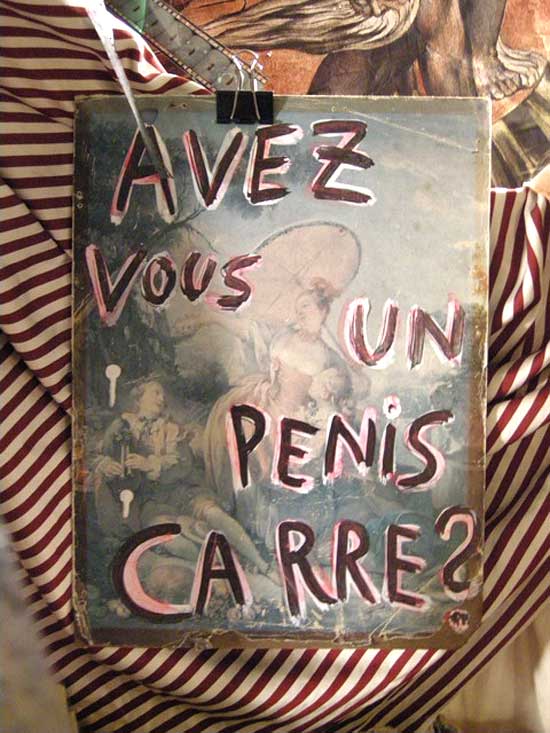

Freespace Exhibition and Performances

59 Rivoli Aftersquat, Paris, December '09

'Do you have a square penis?' By Swiss-Morrocan

Paris correspondent, participant artist, Angie Eng

The romantic vision of the artist in his solitude, poverty-stricken, hyper-intelligent delusional world, the tabloid reader may even imagine him living and working in a graffitied, Lower East Side 80's freezing cold moldy squat next to the crack queue. Those were the days, they say… before the real estate boom and diamond skulls. Don't panic, there are still freezing cold, stinky albeit renovated spaces to produce art for little or no rent (in Paris, that is.) Last December (In the aftermath I refer to as my 'temporary creative masochistic state') I plunged myself into heading two weeks of artist organized art in a former squat in Paris.

To rebel against the Christmas consumer rush on Rue de Rivoli, I recruited my most faithful to help run Freespace a series of free concerts, performances, readings and an exhibition based on the theme of public space.

Even though this is rumoured to be the 3rd most visited cultural venue in Paris, I stumbled upon it during an artist tour, 2 weeks after its re-opening as an official, legal space for artists to work and play. This 6-story building sandwiched between the Louvre and Hotel de Ville, includes a dazzling storefront gallery space, 30 open artist studios and a micromuseum. I have to admit my original intent was not to organize a series of art events, but to do a site specific window installation of a faux travel agency selling public space. My arm was twisted and it had been a while since I organized some art events. Et voilà…

Freespace Exhibition and Performances December 8-20, 2009, 59 Rivoli Aftersquat, Paris

Participating artists: A-li-ce, Cecile Babiole, Luc Barrovecchio, Christiane Blanc, Nina Canal, Steve Dalachinsky, Angie Eng, Elizabeth Gilly, HeHe (Helen Evans, Heiko Hansen), Kentaro, Stuart Krusee, Cecile Le Combe, Les hautsdeplafond (Pierre Lutic & Philippe Gautier), Thierry Madiot, Agathe Max, Mectoob, Yuko Otomo, Margarita Papazoglou, Plectrum, Claude Parle, Atau Tanaka

Participating artists: A-li-ce, Cecile Babiole, Luc Barrovecchio, Christiane Blanc, Nina Canal, Steve Dalachinsky, Angie Eng, Elizabeth Gilly, HeHe (Helen Evans, Heiko Hansen), Kentaro, Stuart Krusee, Cecile Le Combe, Les hautsdeplafond (Pierre Lutic & Philippe Gautier), Thierry Madiot, Agathe Max, Mectoob, Yuko Otomo, Margarita Papazoglou, Plectrum, Claude Parle, Atau Tanaka

Grace à the city of Paris, the former Bank of Lyon known as Chez Robert on 59 Rivoli was 'regulated' and renovated after years of squatter status. Listen to the interview with Swiss-Morrocan one of the head chiefs of the 'Aftersquat'.

Angie Eng interviews Swiss Morrocan

After my eye-opening experience with 59 Rivoli Aftersquat, I decided I would write this article and do a Q/A with 2 other artist run spaces where I had presented work in the last year: La Générale en Manufacture, Sèvres and Les Voutes (affiliated with Les Frigos). I found it would be impossible and almost suicidal to make my own art and even fathom running an artist run place all year round. These artist/organizers are definitely a special breed, a rare species in a time when the collective body decomposed decades ago.

All three spaces are artist collective run, currently government owned, legalized spaces for artists to work and organize events and artists' residencies. All of them pay for electricity, insurance, water. (In some cases, 'rent' and also former collective debts from either unpaid utility bills or renovations) Although they share a similar paradigm of alternative art space, each is unique in their intent and vision of being on the periphery or even outside the inside art world.

I consider Les Voutes to be one of the more beautiful places to make art in Paris, 59 Rivoli to be run by the most friendly and unpretentious artists I've ever met and La Generale at Sevres too new to say NO.

On the side, France still has one of the largest cultural art budgets in the world (2.8 billion in 2009 or $622 per person per year). By the way, the 2009 NEA cultural arts budget in America was 265 million or 86 cents per person per year. However, politics and administration goes hand in hand with government funding. In France, wanting a piece of that pie, artists are suggested to create associations or mini-non profit organizations, sign contracts abiding by city legislation and regulations in order to plan their artistic activities around 'festivals.' Count the logos at the bottom of the invites to get an idea of the size of each slice. With these figures, doing independent events 100% artist run in government owned buildings, is to put it frankly, an illusion. Be that as it may, I'm grateful that these spaces exist grace à the Ville de Paris and have not been burned down or sold to luxury housing developments like the City of New York. I'm still not sure if larger cultural budgets change the quality of art, but we can all agree its better to have more than less in the diffusion of cultural practice.

"In my opinion, the art market is a dead donkey covered with flies.

It's made for a bunch of rich happy few.

We always see the same ridiculous official artists

promoted through these kind of private circles

with no hope of seeing something new...

We do not want to be a part of this private joke.

We expect nothing from others

(governement, official organizations, etc.)

We do what we have to and want to do."

-Pierre Wayser, Les Voutes

It's made for a bunch of rich happy few.

We always see the same ridiculous official artists

promoted through these kind of private circles

with no hope of seeing something new...

We do not want to be a part of this private joke.

We expect nothing from others

(governement, official organizations, etc.)

We do what we have to and want to do."

-Pierre Wayser, Les Voutes

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes

Building: 19 rue des Frigos 4 underground train tunnels approximately 1000 sq feet each and a garden

Established: 1998

Owner: former owner was SNCF then, le Réseau Ferré and then City of Paris since 2003

Regulated: 2000

Purpose: 'We decide to create a cultural association (and a garden) to rule the place. First to show our work, then the one from friends...'

Website: http://lesvoutes.org http://les-frigos.com

Les Voutes Artistic directors: Bruno Herlin and Pierre Wayser

Contract terms:

We do not receive any kind of funds or money !

We do not ask for money !

We do not want their money !

We do not have to say "thanks"!!

We just use some differents networks of international artists and share the expenses.'

Information provided by Pierre Wayser

59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivioli Aftersquat

Building: 59 rivoli, 6 stories, plus storefront gallery

Squat established: 1999

Owner: Bank of Lyon and then bought by the City of Paris

Expulsion by court of law: 2000

Regulated: 2001 (renovated and closed during 2006-2009)

Purpose: open studios to public everyday (except Monday) exibition space, artist studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 core members, around 30 artists working in building

Website: http://www.59rivoli.org

Contract terms: all artists are door greeters for 1 hour /week, each artist pays $160 for utility bills, building closes at 8pm

Information provided by: Swiss Morrocan

La Générale, Sévres

La Générale, Sévres

Building: original building on rue du Général Lasalle Paris Belleville new location: 60,000 square foot

Squat: established in 2005

Owner: National Education Ministry

Expulsion by court of law: 2006

Regulated: 2007 relocation to Sévres

Purpose: exibition spaces, wood and metal workshops, photographic studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 official members

Website: http://www.la-g.org

Art Residency directors: Sylvain Gelinotte and Jerome Guige

La Générale profile: Painters,VJs, scupltors, conceptual artists, performers, photographers, musicians, video artists, poets, drawers, young or older (mostly in the 30s), french and foreigner nationals (mostly are french speakers), somewhat famous and also perfectly unknown.

Contract terms: With the Regional Minister of Cultural Affairs (DRAC): 'they pay the rent and we run the space for the benefit of our work and visiting artists. Using the space to run a company or renting it forbidden'

Association Rules: $70 per month membership fee to pay for power, internet connection and the insurance that covers everyone

Information provided by: Jerome Guige

Angie Eng, Paris, January 26, 2010

Thursday, December 24, 2009

Bonnie Marranca of PAJ Publications

PAJ Founder interviewed in

Germantown, New York

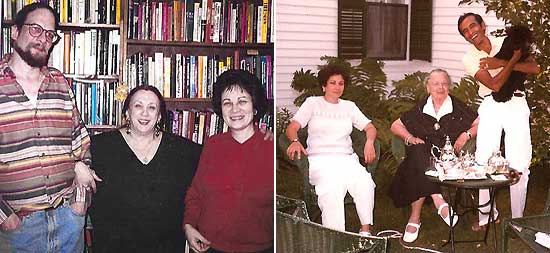

Artist Organized Art Interviews Bonnie Marranca, Founder, Publisher and Editor of PAJ Publications/PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art. The interview occurred in August of 2008 in Germantown, N.Y.

Bonnie Marranca, with Robert Wilson drawing behind her, Berlin, 2009

JS: How did you start PAJ logistically and why did you start it?

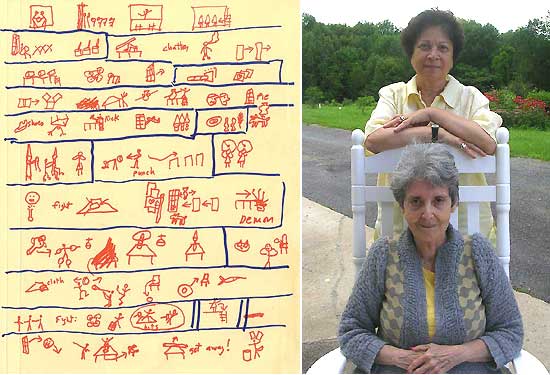

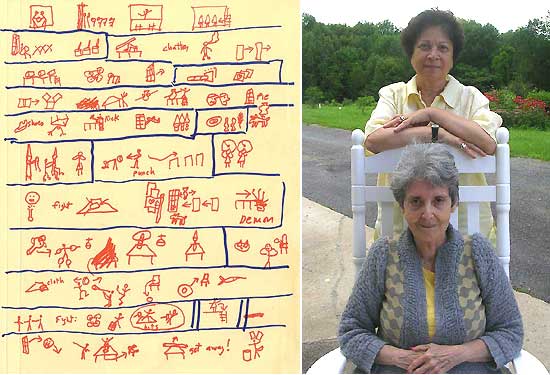

left: Drawing of his play Maria del Bosco, by Richard Foreman from PAJ’s Performance

Drawings portfolio series. right: PAJ publisher with the playwright Maria Irene Fornes, 2009

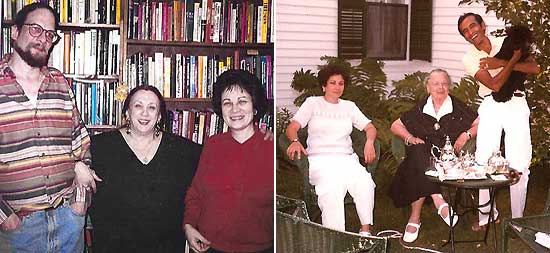

left: At JFK Airport with German playwright Heiner Müller.

right: In London, 2009, at a PAJ event featuring Meredith Monk.

left: Living Theatre artistic directors, Judith Malina and Hanon Resnikov with the PAJ

publisher at her New York City apartment. right: PAJ publishers, Bonnie Marranca and

Gautam Dasgupta, visiting French author Marguerite Yourcenar at her

home in Maine, a few years before her death in 1987.

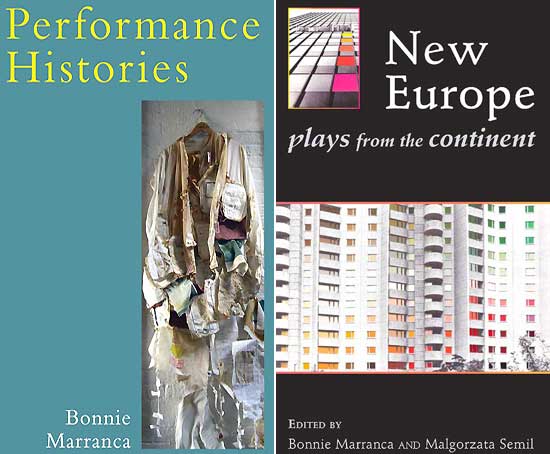

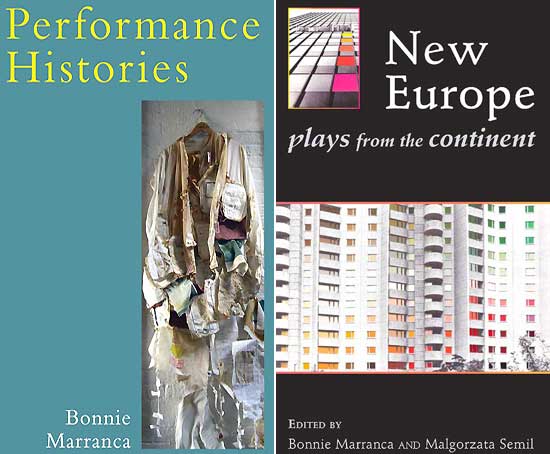

left: Cover of Performance Histories (2008), featuring Alison Knowles performance sculpture,

Book Jacket. right: Cover of New Europe: plays form the continent (2009),

featuring artwork by German artist Bernd Trasberger.

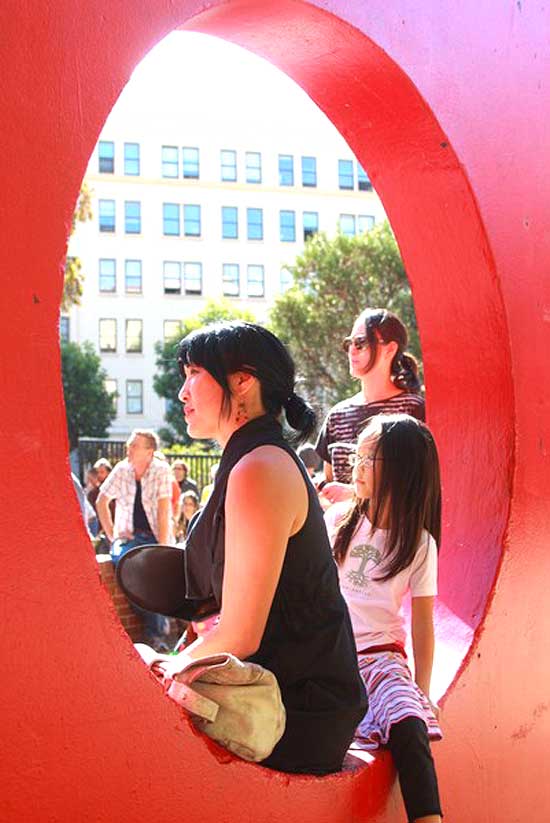

Bonnie Marranca standing in a Richard Serra sculpture.

Bonnie Marranca (www.bonniemarranca.com) is publisher and editor of the Obie Award-winning PAJ Publications and PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art (originally called Performing Arts Journal), which she co-founded in 1976. She has written three collections of criticism: Performance Histories, Ecologies of Theatre, and Theatrewritings, the recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. Among the many anthologies she has edited are: Plays for the End of the Century; American Dreams: The Imagination of Sam Shepard; and The Theatre of Images, one of the seminal books of contemporary theatre. Her writings have been translated into fifteen languages. She is a Guggenheim Fellow and Fulbright Senior Scholar who has taught in many universities here and abroad, including Columbia University, Princeton University, NYU, Duke University, the University of California-San Diego, Free University (Berlin), and Autonomous University/Institute for Theatre (Barcelona). She is Professor of Theatre at The New School/Eugene Lang College for Liberal Arts.

PAJ (www.mitpressjournals.org/paj) is admired internationally for its independent critical thought and cutting-edge explorations. PAJ charts new directions in performance, video, drama, dance, installations, media, film, and music, integrating theater and the visual arts. Artists' writings, critical commentary, interviews, and a special review section for performances and gallery shows are highlighted along with plays and performance texts from around the world. New features include Performance Drawings portfolios and the Art, Spirituality, and Religion ongoing series. In 2009, the journal celebrates its 33rd year of publishing.

PAJ Founder interviewed in

Germantown, New York

Artist Organized Art Interviews Bonnie Marranca, Founder, Publisher and Editor of PAJ Publications/PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art. The interview occurred in August of 2008 in Germantown, N.Y.

Bonnie Marranca, with Robert Wilson drawing behind her, Berlin, 2009

interview by Joshua Selman

JS: How did you start PAJ logistically and why did you start it?

BM: PAJ (www.mitpressjournals.org/paj) was conceived in 1975 by Gautam Dasgupta and me while we were studying in the doctoral program at CUNY-the Graduate Center, in New York. We were also critics for the SoHo Weekly News at that time. We had the academic background, but this very lively time in the 70s was a great period for video art, the beginnings of performance art, experimental theatre—such as the work of Robert Wilson, Richard Foreman, Mabou Mines. There were many so things going on . . . Meredith Monk’s work, Philip Glass, new playwrights. We were seeing all of this work, while at the same time having a very traditional theatre background in graduate school. In effect, we had both the traditional grounding and the new aesthetics that we were grappling with as critics. So you could say that we were studying the history of theatre and the repertoire at the same time that the new work was offering its critique.

It also gave us the possibility of having, at our fingertips, the scholars and translators who were really knowledgeable about the dramatic repertoire and the history of theatre. At the same time we came to be friends with several generations of artists in so many different fields. We were not happy with the criticism that was in the major theatre journal of the time, The Drama Review, because it was very descriptive and not analytical. The coverage in The New York Times and comparable magazines and newspapers wasn’t very challenging. There were new art forms, and new ways of making theatre that were really not sufficiently understood or addressed.

left: Drawing of his play Maria del Bosco, by Richard Foreman from PAJ’s Performance

Drawings portfolio series. right: PAJ publisher with the playwright Maria Irene Fornes, 2009

We had a different vision of theatre and of criticism at that time. We thought we could make a journal that could become involved with new forms of writing and could deal with the new performance aesthetics as well as having the commitment to dramatic literature. Between the two of us, Gautam and I found a printer, learned editing, production, and worked on marketing, sales, and distribution. We quickly had our own typesetting equipment and did everything in-house. So, from the start we were pretty self-sufficient. We began to hand out flyers at theatres, and worked on getting mailing lists and subscriptions in the universities and in libraries. That’s essentially how we started. The publishing house was never part of any university or organization that provided money or staff.

JS: Can you describe the development of PAJ, and its later involvement with Johns Hopkins University Press and MIT Press?

BM: We began to publish the journal and set up a non-profit 501(c)3, by the time we had published the first issue, in May 1976. Then, three years later, we began publishing books, and called the publishing house PAJ Publications. The journal was then known as Performing Arts Journal (the name was changed in 1998 to PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art) We went along this way for quite a while and continued to publish books of plays and books of essays; the journal featured international coverage in essays, interviews and dialogues, new writing, performance reviews and festival reports. There was simply so much material and so many interesting things to cover that we felt we couldn’t contain it in a journal three times a year. So, we started on books and we had many of the same authors move from the journal to books as well.

left: At JFK Airport with German playwright Heiner Müller.

right: In London, 2009, at a PAJ event featuring Meredith Monk.

About ten years later, in the late-eighties, we made an agreement with Farrar, Straus and Giroux, the very highly regarded literary publishers, to distribute our books. That lasted for three years. One of the reasons we went to them was that we wanted to start publishing fiction. We tended to do fiction of the playwrights we knew, like Ken Bernard and Harry Kondoleon. The late-eighties was a period of great difficulty, with the so called “culture wars” and funding controversies. The tide had turned against heavy support for experimental theatre and the downtown scene, so we knew we had to figure out a way to safeguard the press.

Eventually we made an agreement with The Johns Hopkins University Press, around 1991, and PAJ became an imprint of Johns Hopkins. They distributed our backlist as well, which was about eighty-five titles by this time. PAJ Books became a series under this imprint, and JHUP financed the new titles. We commissioned forty books, including the Art+Performance series for performance and new media (with volumes on Yvonne Rainer, Meredith Monk, Bruce Nauman, Gary Hill and others. The journal was published in their journals division, but we always maintained control of our name and always owned the journal. That agreement lasted for about ten years. Then we went to MIT Press, around 2001. That’s where we remain, though MIT Press has no involvement with the books. PAJ went back into financing and publishing its own books in 2006. We have about sixty titles now in print, distributed by Theatre Communications Group (www.tcg.org)

JS: What is the editorial premise of PAJ?

BM: PAJ Publications was founded to publish, promote, and support new work, lost or forgotten works of the past, and to develop a very rigorous idea of criticism. By that I don’t mean theory, but criticism and fine critical writing—that’s what I think PAJ has been known for. In addition, there is the publication of new American drama and works of translation.

left: Living Theatre artistic directors, Judith Malina and Hanon Resnikov with the PAJ

publisher at her New York City apartment. right: PAJ publishers, Bonnie Marranca and

Gautam Dasgupta, visiting French author Marguerite Yourcenar at her

home in Maine, a few years before her death in 1987.

Looking back over three decades of books and journals, by now we’ve published over one thousand plays and performance texts, translated from twenty languages. We’ve published about one hundred and forty books and ninety journals so far. PAJ Publications is one of the major play publishers in the English-speaking world. We’ve always held the line when so much of academia and the world of the arts moved strongly toward theory. I believe very much in the primacy of the artwork, and the experience of the writer or critic, so I am not interested in applied theory. I don’t consider PAJ an academic journal. I believe it should be a kind of fine literary writing grounded in knowledge of the field and the experience of individual works. That’s been true for most of the history of the journal. Our format has been a combination of essays, interviews and dialogues, plays or performance texts, festival reports, reviews of performance.

When Performing Arts Journal changed its name a decade ago to PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art, it was because I wanted to have theatre and visual arts move closer together in the journal. The art world was continuing to do more performance, there were installations, video, media, photography, and all kinds of things that could be looked at in terms of performance and spectatorship. We were already covering, theatre, dance, and music.

left: Cover of Performance Histories (2008), featuring Alison Knowles performance sculpture,

Book Jacket. right: Cover of New Europe: plays form the continent (2009),

featuring artwork by German artist Bernd Trasberger.

When we started the journal, what constituted theatre or performance was rather a small world considering where the notion of performance went in thirty years. Dramatic literature is no longer the center of study in theatre. People don’t have the same interest in playwriting, but are more interested in performance. In the twentieth century, there are two histories of performance, one from the theatre world, and one from the art world, so that if you are in an art department, you study a history of performance that’s entirely different from what you would study in a theatre department. I’m trying to bring them closer together within the journal. A larger, more comprehensive history of performance ideas, that’s my main goal, and it has been for the last ten years.

Bonnie Marranca standing in a Richard Serra sculpture.

Read the full interview.

Included in the full interview, Bonnie Marranca speaks to the following:

Included in the full interview, Bonnie Marranca speaks to the following:

Bonnie Marranca (www.bonniemarranca.com) is publisher and editor of the Obie Award-winning PAJ Publications and PAJ: A Journal of Performance and Art (originally called Performing Arts Journal), which she co-founded in 1976. She has written three collections of criticism: Performance Histories, Ecologies of Theatre, and Theatrewritings, the recipient of the George Jean Nathan Award for Dramatic Criticism. Among the many anthologies she has edited are: Plays for the End of the Century; American Dreams: The Imagination of Sam Shepard; and The Theatre of Images, one of the seminal books of contemporary theatre. Her writings have been translated into fifteen languages. She is a Guggenheim Fellow and Fulbright Senior Scholar who has taught in many universities here and abroad, including Columbia University, Princeton University, NYU, Duke University, the University of California-San Diego, Free University (Berlin), and Autonomous University/Institute for Theatre (Barcelona). She is Professor of Theatre at The New School/Eugene Lang College for Liberal Arts.

PAJ (www.mitpressjournals.org/paj) is admired internationally for its independent critical thought and cutting-edge explorations. PAJ charts new directions in performance, video, drama, dance, installations, media, film, and music, integrating theater and the visual arts. Artists' writings, critical commentary, interviews, and a special review section for performances and gallery shows are highlighted along with plays and performance texts from around the world. New features include Performance Drawings portfolios and the Art, Spirituality, and Religion ongoing series. In 2009, the journal celebrates its 33rd year of publishing.

Sunday, November 01, 2009

WONDERLAND Exhibition

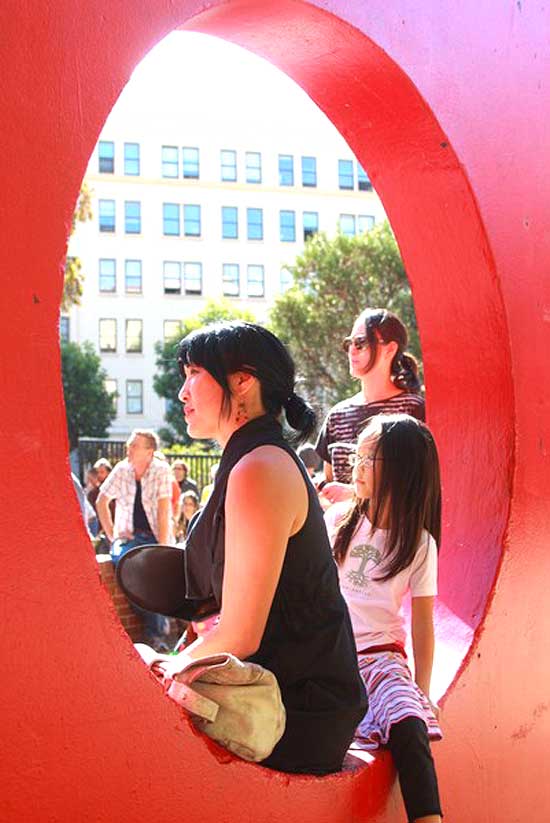

San Francisco Tenderloin, October 17, 2009

Curated by Lance M Fung

City of San Francisco, streets of The Tenderloin

City of San Francisco, streets of The Tenderloin

Our cultural institutions often rejuvenate themselves at the expense of the disempowered. The avant garde often exploits fringe neighborhoods, brokering between corporate and vernacular cultures. This opens the door to gentrification. Yet, we find ourselves sympathetic to the impact of local material conditions. In The Tenderloin these include homelessness, joblessness, illiteracy, crime, disease and epidemics such as AIDS, hunger, poverty, drug addiction, alcoholism, lack of health care and environmental decay. In short, the untidy social effects of the “advancement” we call globalization. Locals are explained away.

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

"Block Party" event, October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Wonderland seems to take on a particular challenge, namely how to take local culture seriously when the dominant culture precludes difference, cultural, racial and sexual as an insidious evil. The challenge for Wonderland is to be locally inclusive and to negate the attraction/repulsion process of the global art market. Using the title “Wonderland” the dominant strategies, such as exploiting minority artists by insisting they source local street violence as their unique selling point or that they themselves signify misery remarketed, are surprisingly countered.

"Fear Head" by Roman Cesario and Mitsu Overstreet

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

A resident follows the exhbition "Wonderland"

in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Instinctively, the artists, organizers and partners of Wonderland Exhibition, all volunteers, follow early signs of change in the air. They are taking to the streets of The Tenderloin, to engage local community, to make work which is a synthesis by artist and community. The opportunity is to finally truly turn outward, to engage with the larger society, to work with social creativity and invent new forms of organizations that suit ongoing needs of creative synthesis. They are picking up where we left off before the blight of the NEA led to the cancerous growth of the commercial gallery and auction houses. The exhibition is to push the boundaries of local culture as far as it can.

in performance: Night At The Blackhawk

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Wonderland Symposium, with Lance Fung at the Warfield Theater, Oct 18, 2 - 4 pm

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Thomas Kosbau interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Chris Burch, Niki Shapiro, and Lance Fung at Boeddeker Park

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

"Block Party" event, October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Lars Chellberg interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

Layman Lee interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

Participating Artists at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

The exhibition is free and open to the public from October 17th, with a symposium on the 18th, and will close November 15th. www.wonderlandshow.org

The exhibition Wonderland is a large, multi-sited event born of, and responding to the rich diversities of San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. The tenor of this project is truly unique, and will call upon the collaborative efforts of the neighborhood’s residents, city organizations like the North of Market Community Benefit District the exhibition’s sponsor, and a large number of cutting edge artist teams from the Bay Area and around the world. As in his previous internationally recognized projects, the exhibition’s curator, Lance Fung is dedicated to the ideas of collaboration, community and social engagement as a means of bringing the highest level of contemporary art to audiences from all walks of life.

Participating Artists: Per Åhlund, Barry Beach, Ken Beasley, Alex Beckman, Brian Bixby, Charles Blackwell, Alex Braubach, Britteny, Christopher Burch (WNA,) Roman Cesario, Lars Chelberg, Colby Claycomb, Sydney Cooper, Rick Darnell, Jaine Dickens, Christian Kurt Ebert, Jonathan Fung, Kaif Ghaznvi, Geoffrey Grier, Doug Hall, Melkorka Helgadottir, Malak Helmy, Jessica Higgins (WNA,) Noritoshi Hirakawa, Monika Jones, Mathias Josefson, Erika Knerr (WNA,) Thomas Kosbau, Layman Lee, Mark Lee, Agustin Fernandez Mallo, Lauren Marsden, Jeff Marshall, Mike Maurillo, Lynne McCabe, Andrew McClintock, John K Melvin (Project Director), Regina Miranda, Ranu Mukherjee, Patricia Niedermeier, Erik Otto, Mitsu Overstreet, Kara Pajewski, Txutxo Perez, George Pfau, Leif Percifield, Christophe Piallat, Rex Resa, Brandon Robinson, John Roloff, Kit Rosenberg, Jeff Roysdan, Jorge Satorre, Niki Savage, Joshua Selman (WNA,) Stix, Owen Takabayashi, Kristin Timken, Brandon T Truscott, Thomas Watkiss, Wilton Woods, Izumi Yokoyama, Steven Zettler, and others...

San Francisco Tenderloin, October 17, 2009

Curated by Lance M Fung

City of San Francisco, streets of The Tenderloin

As a participating artist in the Wonderland Exhibition, I'm asking myself why a large scale contemporary art exhibit opening in The Tenderloin in San Francisco and curated by one of today’s most respected and publicized curators, Lance Fung, is titled, of all possible titles, “WONDERLAND?” The Tenderloin is a neighborhood marginalized to the point of reputation. Yet surprisingly, the title “Wonderland” correctly identifies and responds to a hidden cultural dilemma facing any group of artists approaching this historic community.

City of San Francisco, streets of The Tenderloin

Our cultural institutions often rejuvenate themselves at the expense of the disempowered. The avant garde often exploits fringe neighborhoods, brokering between corporate and vernacular cultures. This opens the door to gentrification. Yet, we find ourselves sympathetic to the impact of local material conditions. In The Tenderloin these include homelessness, joblessness, illiteracy, crime, disease and epidemics such as AIDS, hunger, poverty, drug addiction, alcoholism, lack of health care and environmental decay. In short, the untidy social effects of the “advancement” we call globalization. Locals are explained away.

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

"Block Party" event, October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Wonderland seems to take on a particular challenge, namely how to take local culture seriously when the dominant culture precludes difference, cultural, racial and sexual as an insidious evil. The challenge for Wonderland is to be locally inclusive and to negate the attraction/repulsion process of the global art market. Using the title “Wonderland” the dominant strategies, such as exploiting minority artists by insisting they source local street violence as their unique selling point or that they themselves signify misery remarketed, are surprisingly countered.

"Fear Head" by Roman Cesario and Mitsu Overstreet

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

The Wonderland Exhibition also speaks to the need to reform dominant culture institutions, such as the Museum of Modern Art or Lincoln Center, to artist spaces and organizations based in ethnic communities that alone address a lack of multiculturalism and tolerance. A lack which has grown since Ronald Reagan left the office of Governor of California to become President of the USA and allowed a twenty year surge of neo-conservative intolerance, which in the past eight years has become extreme in the dominant culture. Wonderland is an attempt to signal the way back to a positive progressive footing, to organize beyond the survival tactics of the past twenty years and to pick up where others left off before the heterogeneous world was cast in gray.

A resident follows the exhbition "Wonderland"

in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Instinctively, the artists, organizers and partners of Wonderland Exhibition, all volunteers, follow early signs of change in the air. They are taking to the streets of The Tenderloin, to engage local community, to make work which is a synthesis by artist and community. The opportunity is to finally truly turn outward, to engage with the larger society, to work with social creativity and invent new forms of organizations that suit ongoing needs of creative synthesis. They are picking up where we left off before the blight of the NEA led to the cancerous growth of the commercial gallery and auction houses. The exhibition is to push the boundaries of local culture as far as it can.

Perhaps it’s time for Wonderland. The growing weight of the nation’s social problems were paid for by independent local communities, while the nation’s prosperity accrued to the establishment arts and the military. As artists, we’ve played along with a prestige game and lost. We’ve been robbed of our social imagination, served as an inoculation against awareness and have done the hard work of self censorship to the point of obscurity. Count the projects left unproduced, the low birth rate of institutions and a general lack of experimentation as the cost of the Reagan/Bush/Helmes/Bush era. This shadow over what was once our cultural community chills us even now. But, the Wonderland Exhibition funnels volunteerism with multiculturalism allowing artists back into local community culture.

in performance: Night At The Blackhawk

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Wonderland celebrates the recent gains made at the NEA with a new attitude, an attempt to live, work and make art in a flamboyant and joyful Tenderloin community. During the twenty year neo-conservative era, the NEA used the Chair's veto to publicize censorship. Neo-conservatives condemned the Endowment for its attention to public impact, social need, tolerance, experimentation and a support of “public service” concepts. By contrast Wonderland celebrates the evolution of new and existing organizations, such as the Wonderland Neighborhood Association, as necessary to a fuller cultural life. The volunteer Exhibition remains nimble rather than being bogged down attracting funders.

Wonderland Symposium, with Lance Fung at the Warfield Theater, Oct 18, 2 - 4 pm

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Artists have an unusual potential to exercise social imagination. From Fluxus of the 1960’s to The International Artists Museum and its connection to the Solidarity Movement of 1980’s Poland, the Artists Space movement in the USA from the 1960’s to the 1980’s, the ability of artists to impact and innovate the organization structure itself has been remarkable. Wonderland celebrates a return to this type of artist collaboration in the structure of organization and is turning away from an era where the drive of existing corporations to perpetuate themselves has choked off all creative options.

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

The project is coming out of the closet creatively, socially and culturally. In the past eight years a majority of Americans were forced to give up their own liberties even if they were willing to risk allowing those liberties to others described as terrorists, dangerous people of color, people with aids, homosexuals, illegal aliens, foreigners, feminists, community organizers and those criminals, the artists. Disempowered communities have found themselves profiled and marginalized, excluded, undercounted, prosecuted, silenced, bashed, spied on, controlled, unemployed, underemployed, defunded, put out of business and run out of town by a growing corporate elite. Yet, Wonderland’s agility lets it by-pass corporatism’s attack on community content and public funding using volunteerism and public service.

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Despite an era of intolerance, racism, greed, religious fundamentalism, homophobia, rabid patriotism and media based brain washing we are picking up where we left off. Wonderland is a signal from the Tenderloin community to the established art world to return to supporting difficult and challenging art and to enlarge art audiences and art concerns by engaging wider publics through their collaboration. Ahead of the curve, the exhibition calls out directly to multicultural reality.

Thomas Kosbau interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

As artists we know we have to earn public recognition of our significance. Communities are still untrusting of what we do. The stigma that artists are fooling the public persists. For a change, this effort includes transparency, sharing power and information with The Tenderloin community.

Visitors at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

Wonderland is happening at a time of great chaos inside our corporations. As our infrastructure sustains shock after shock, many corporations, such as banks, insurance companies, governments and educational institutions are manipulating facts, ignoring inquiries, blaming, scandalizing and creating the false impression that things are fine while hoping they don’t get worse. For this reason the artists have chosen a new path of reliance and affiliation based on volunteerism, truthfulness about capacity and relevance to the Tenderloin community. We know we will be doing without the resources available to established art institutions, what is amazing is how much we’ve been able to do without those resources and how little compromise we’ve had to make to cultural conservatism because of it.

Chris Burch, Niki Shapiro, and Lance Fung at Boeddeker Park

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

"Block Party" event, October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

It is not the support that makes art and art making itself is not a business. This opportunity is for nurturing young artists and for engaging works that champion those who have been discounted in their communities: the culturally diverse, feminists, gay men and lesbians, the disabled, the upstarts and those with ideas that challenge the social fabric. We simply must put an end to the corporate ice age in the art of our communities. It's an experiment that asks the public to revalidate the relationship between creativity and social change.

Lars Chellberg interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

I've known Lance Fung for a long time. As a curator Lance is dedicated to ideas and ideals far outside the mainstream, possibly dangerous to the well being of the institution and possibly to the artist community as a whole. While the NEA was backing away from its once strong commitment to challenging work, Lance crossed sides from commercial dealing to the non-profit world of art out of a need to put experimentation ahead of survival. It is interesting that with Wonderland he has proceeded with a nearly wholesale disengagement from support funding in an effort to rekindle a call to social change at the earliest moment possible.

Layman Lee interaction for "Stake"

Wonderland Exhibition in The Tenderloin, City of San Francisco

Photo: Wonderland Exhibition

One of the benefits we hope to achieve is a mechanism to keep community support of art close to its makers of art. Because Wonderland’s projects vary specifically by the community served, by the type of art presented and by the in-kind/volunteerism pledged, they are not as easily spotted as say a "museum" or "theater," but perhaps their impact will be far greater.

Joshua Selman, Participating artist, Wonderland 2009

Participating Artists at the "Block Party" event by WNA

Site of Wonderland Neighborhood Association (WNA)

October 17th, 11 - 5 pm

The exhibition is free and open to the public from October 17th, with a symposium on the 18th, and will close November 15th. www.wonderlandshow.org

The exhibition Wonderland is a large, multi-sited event born of, and responding to the rich diversities of San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. The tenor of this project is truly unique, and will call upon the collaborative efforts of the neighborhood’s residents, city organizations like the North of Market Community Benefit District the exhibition’s sponsor, and a large number of cutting edge artist teams from the Bay Area and around the world. As in his previous internationally recognized projects, the exhibition’s curator, Lance Fung is dedicated to the ideas of collaboration, community and social engagement as a means of bringing the highest level of contemporary art to audiences from all walks of life.

Participating Artists: Per Åhlund, Barry Beach, Ken Beasley, Alex Beckman, Brian Bixby, Charles Blackwell, Alex Braubach, Britteny, Christopher Burch (WNA,) Roman Cesario, Lars Chelberg, Colby Claycomb, Sydney Cooper, Rick Darnell, Jaine Dickens, Christian Kurt Ebert, Jonathan Fung, Kaif Ghaznvi, Geoffrey Grier, Doug Hall, Melkorka Helgadottir, Malak Helmy, Jessica Higgins (WNA,) Noritoshi Hirakawa, Monika Jones, Mathias Josefson, Erika Knerr (WNA,) Thomas Kosbau, Layman Lee, Mark Lee, Agustin Fernandez Mallo, Lauren Marsden, Jeff Marshall, Mike Maurillo, Lynne McCabe, Andrew McClintock, John K Melvin (Project Director), Regina Miranda, Ranu Mukherjee, Patricia Niedermeier, Erik Otto, Mitsu Overstreet, Kara Pajewski, Txutxo Perez, George Pfau, Leif Percifield, Christophe Piallat, Rex Resa, Brandon Robinson, John Roloff, Kit Rosenberg, Jeff Roysdan, Jorge Satorre, Niki Savage, Joshua Selman (WNA,) Stix, Owen Takabayashi, Kristin Timken, Brandon T Truscott, Thomas Watkiss, Wilton Woods, Izumi Yokoyama, Steven Zettler, and others...

Artist Organized Art

as seen in:

help by linking us (click in box, copy code, paste code into your site or blog page)

http://artistorganizedart.org

Makes Example: http://artistorganizedart.org

XML ::.. bookmark this page: del.icio.us Furl reddit Yahoo MyWeb

Get More Involved: Donate Now | Log In | Sign Up Now | Subscribe | About Us