Previous Post Next Post

Friday, March 7th, 2008

Embarrassment and Address

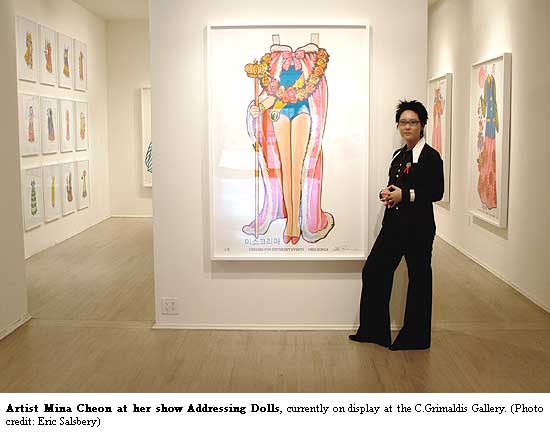

Mina Cheon’s Addressing Dolls at the C.Grimaldis Gallery

Mina Cheon’s Addressing Dolls at the C.Grimaldis Gallery

Baltimore, Maryland

Dollhouses first became popular in 17th century Western Europe. One of the most famous patrons of dollhouses at the time was Petronella Oortman of Amsterdam. If you go to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam you can see some of her collection. Painted large upon the wall of the exhibition room, in English and Dutch, you learn that Oortman spent from 20,000 to 30,000 guilders at a time on the houses and their furniture, a price which could have purchased a real house on one of Amsterdam’s canals. This information is presented as shocking, and Oortman as wasteful. This is because dolls are not real, so they cannot appreciate or be comforted by their houses. Such devotion and extravagance lavished by the living on the non-living, however beautiful the outcome may be, is embarrassing. Embarrassing because care is given to that which is considered not to deserve it — the empty husks of dolls.

While embarrassment is usually thought of as a negative concept, in the artwork(s) of Mina Cheon’s exhibition Addressing Dolls it is a positive, strong and emancipating emotion. This is because embarrassment comes from being on unfamiliar ground. It comes from being subversively open to what is usually considered unimportant or impossible. Addressing Dolls foregrounds this unfamiliar ground by shining light on familiar tropes which have been manipulated within the thrust for Westernization in South Korean culture. In this sense the artwork functions in two ways: to focus our attention on the ways different kinds of dolls have been manipulated in Korean culture, and to highlight our own relationship to what is considered other than ourselves.

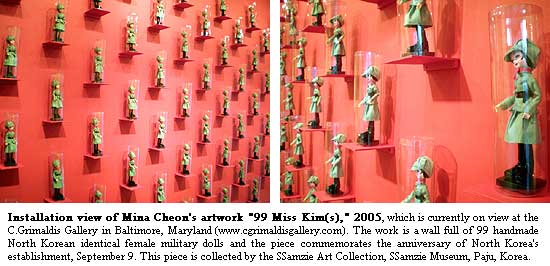

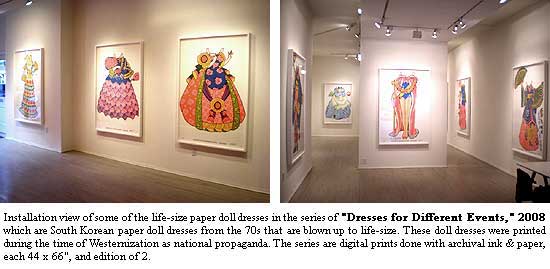

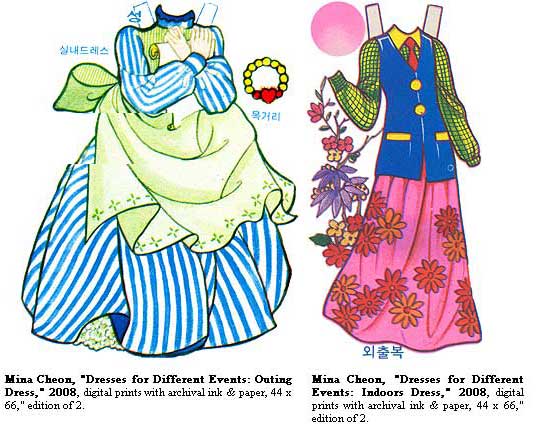

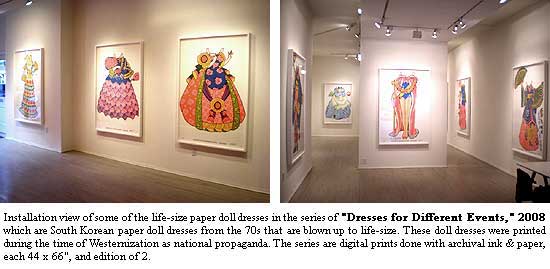

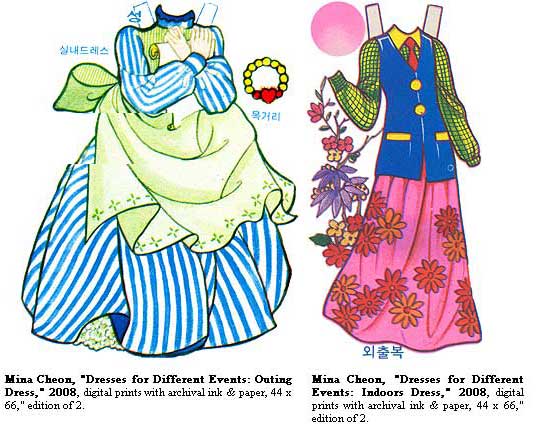

The focus of this exhibition is the trope of the doll. Its use is foregrounded firstly through repetition in 99 Miss Kim(s), which features 99 handmade female military dolls which were used to spread the propaganda of an oppressive North Korea, and secondly in the manipulation of scale in ten types of Dresses for Different Events, where frilly paper doll dresses are enlarged, becoming life-sized. These works call attention to the conflict present within Western and colonizing cultures in both Koreas and the way in which that has led to a conflicted relationship, and Cheon has worked on this cultural distortion by subverting the images and objects themselves. The repeated dolls of North Korean military femme bots and the blown-up Victorianized paper dresses of 70s South Korea do not let the viewer walk by, they do not let the viewer forget. Such a call-to-attention is embarrassing because it puts the viewer on unfamiliar ground by taking given and familiar tropes and putting them out there, exposed and open to scrutiny.

So where does that leave the viewer? Again, putting a positive spin on a term that is usually seen as negative, the viewer is left in a state of stupidity. In a sense, you can say that it is stupid to address dolls, to dress them, to cover them with wealth or ideas or to look towards dolls for answers, since they do not give anything back. However, it is in this state of a removal from what is usually considered intelligence that something new can come about. This removal can be considered a form of address because it is an openness to response, a turning towards and opening to. In this manner it is an address in the sense of location, of where you are dwelling. Such a thinking of the address of stupidity has been developed by philosopher Avital Ronell who argues that stupidity “tends to sever with the illusion of depth and the marked withdrawal, staying with the shallow imprint. Unreserved, stupidity exposes while intelligence hides.” This is what was meant above regarding embarrassment. What Addressing Dolls does is to expose through distortion. In this sense stupidity is that which is left when a positive answer is denied and instead what is held open is the moment of questioning, of the pencil poised above the answer sheet. As Ronell states, “Stupidity makes stronger claims for knowing and for the presencing of knowledge than rigorous intelligence would ever permit itself to make.” Cheon takes the manipulative and damaging tropes of the women as dolls in Korean culture and positivizes it by allowing an interaction with such tropes to become an action of embarrassing us out of ourselves, and allowing something else to become present, a knowledge more rigorous than intelligence would ever allow. Such a positivization is also a part of bringing the exhibition to the US from its showing in South Korea: by bringing Westernization back into the West, a sense of defamiliarization is lodged into the heart of the familiar.

So we become embarrassed addressing something that cannot respond, doubly embarrassed because assumed tropes of how the desire of South Korean female beauty is mimicked by Western standards and shaped by Korean expectations and imitation are exposed and such an exposure enacts a removal from intelligence, from what we know or accept, and thus we are put on unknown or at least unstable ground. The result of this exposure is that there is room kept open for the possible, for new thought. However, in order for such openness to exist, the other that is addressed must be allowed to remain in a position of strength. What is meant here is that it is precisely the other that has the strength to do work that we are not able to do, meaning, to bring us into a presencing of ourselves. In order for this presencing to take place, a relationship of what can be called embarrassment, stupidity or perhaps groundlessness needs to happen. Such a relationship to the other is denied these recent Korean artifacts for girls. However, when these manipulations are exposed and reworked, which is at the heart of Cheon’s work, a space for openness ha

ppens.

So in a sense in the 17th century Oortman could be said to have had the correct attitude after all. To lavish the non-responsive other with extravagance and surplus is a way of keeping its strength alive, of honoring its unknown. As Cheon wrote in a recent piece on the hand, “The dolls are interesting non-beings and a gift of my childhood when my hands were not big enough, strong enough, firm enough to hold scissors.” Perhaps it is only a risky, embarrassing and open relationship with a strong other that might allow us to have the ability to approach ourselves.

Brian Willems is an American assistant professor of literature at the University of Split, Croatia. His essays have appeared in or are forthcoming in artUS, A Tribute to Jean Baudrillard, Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy, From A to : Keywords in HTML and Writing and others. His poems and prose have appeared in Antioch Review, Poetry Salzburg Review, Hotel St George Press and others. He has a book forthcoming on Martin Heidegger and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

This text Embarrassment and Address is written for Addressing Dolls, Mina Cheon’s solo exhibition at the C.Grimaldis Gallery, Baltimore, Maryland, which is on display until March 29, 2008.