at Hudson Franklin Gallery, Chelsea

Mar 20 – Apr 26 2008

correspondent: artist Nicholas Sullivan

Jeremy Boyle’s ingenuity ranges from everyday three-word emails to his students, to solo art shows, like the one now at the Hudson Franklin Gallery in Chelsea, New York. As a student of Jeremy’s, I found his approach to instruction deeply refreshing. Coming from a high school where the emphasis and concentration was either on drawing a tree outside the classroom on a piece of paper with oil pastel (in, gasp, unrealistic colors) or churning through the ridiculous number of still life requirements for the AP art portfolio (I got a 3), Jeremy’s take on the foundations program at UMass made me realize the limitless possibilities within the realm of “art.” No longer would I slave at a charcoal self-portrait, nor would I even take a gander at a set of oil pastels. A new world had been opened up, and I was sailor-diving into it.

I have taken four different classes with Jeremy. It is always quite an unusual comparison between the classes I take with other professors and the ones I take with Jeremy. Where some instructors concentrate overwhelmingly on technique, and what I deem as replication, Jeremy instead pushes concept. We have talked a number of times about the power and value of teaching conceptually strong art earlier in an artist’s formal training. An artist with a strong concept, and the will to achieve it, will take those steps to make it happen. Thus the technique follows the concept. Creative freedom is exactly what Jeremy gave me. It is then when art really became exciting, when those doors were open and the vast expanse of everything lay open before me. It was wonderful.

I have taken four different classes with Jeremy. It is always quite an unusual comparison between the classes I take with other professors and the ones I take with Jeremy. Where some instructors concentrate overwhelmingly on technique, and what I deem as replication, Jeremy instead pushes concept. We have talked a number of times about the power and value of teaching conceptually strong art earlier in an artist’s formal training. An artist with a strong concept, and the will to achieve it, will take those steps to make it happen. Thus the technique follows the concept. Creative freedom is exactly what Jeremy gave me. It is then when art really became exciting, when those doors were open and the vast expanse of everything lay open before me. It was wonderful.

From that point on I was brimming with ideas, some rather outlandish, and some a bit more conventional. Regardless of the idea, Jeremy’s expertise and general knowledge on just about everything constantly came to the rescue. At one point, for instance, I attempted to make a Jell-O mold for a project. I was never able to complete the project, but I brought up my failed Jell-O attempts to Jeremy and off the top of his head he gave me a list of ways that Jell-O could solidify faster as well as hold its shape better. How he knew this was something I ponder quite frequently. Instances such as this occur on a daily basis with Jeremy. His capacity to help, and to provide information is boundless.

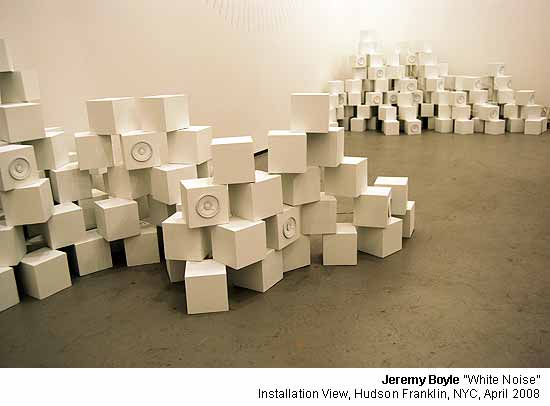

During this current semester I had the opportunity to work with Jeremy as his assistant preparing for his show at the Hudson Franklin Gallery. Every Saturday for about a month or so, I was over at the Boyle residence ready to rock and roll … or sand and paint. The first day we spent the entire day cleaning an astonishingly thick layer of sawdust off everything in his studio. The rest of my days were usually spent working and reworking the exterior of the small wooden boxes involved in his White Noise piece. We deduced at the end of the entire process that each box (there were approximately 250) took around an hour of labor. But, might I say, dear god they looked good. I loved sanding, spackling, and painting. Jeremy’s ipod provided a plethora of new musical discoveries, and I routinely encountered bands I had never heard before (my first day on the job I played 5 straight hours of Morrissey–something that I believe now may have been slowly driving Jeremy insane). The process was exciting to be a part of, and I know that many of my other professors, sadly, would have no art to need help on. Having a professor who is a successful working artist is something that I feel is invaluable. Jeremy’s dedication spanned out of the classroom and into his own studio space, where he spent hours going over every meticulous detail of his pieces, exemplifying a practiced and precise level of craftsmanship.

During this current semester I had the opportunity to work with Jeremy as his assistant preparing for his show at the Hudson Franklin Gallery. Every Saturday for about a month or so, I was over at the Boyle residence ready to rock and roll … or sand and paint. The first day we spent the entire day cleaning an astonishingly thick layer of sawdust off everything in his studio. The rest of my days were usually spent working and reworking the exterior of the small wooden boxes involved in his White Noise piece. We deduced at the end of the entire process that each box (there were approximately 250) took around an hour of labor. But, might I say, dear god they looked good. I loved sanding, spackling, and painting. Jeremy’s ipod provided a plethora of new musical discoveries, and I routinely encountered bands I had never heard before (my first day on the job I played 5 straight hours of Morrissey–something that I believe now may have been slowly driving Jeremy insane). The process was exciting to be a part of, and I know that many of my other professors, sadly, would have no art to need help on. Having a professor who is a successful working artist is something that I feel is invaluable. Jeremy’s dedication spanned out of the classroom and into his own studio space, where he spent hours going over every meticulous detail of his pieces, exemplifying a practiced and precise level of craftsmanship.

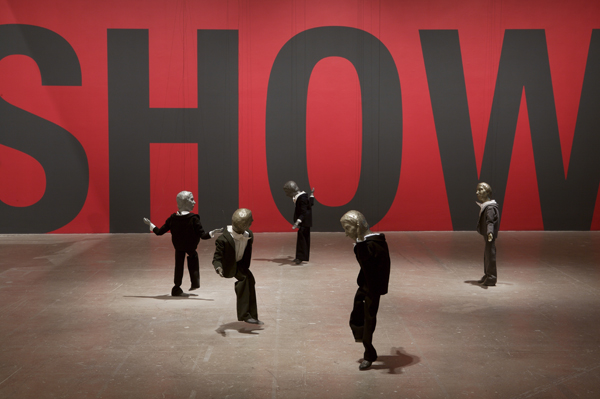

As the show neared, we packaged up the stuff and Jeremy made the long voyage to New York for his installation (which was apparently quite grueling). A few days later a few classmates and myself made the journey to New York for the opening. As we approached the gallery we saw approximately thirty people waiting for the elevator just to get up. I thought to myself, “This is like a godamn Kiss concert.” I hadn’t expected to see such a huge turnout.

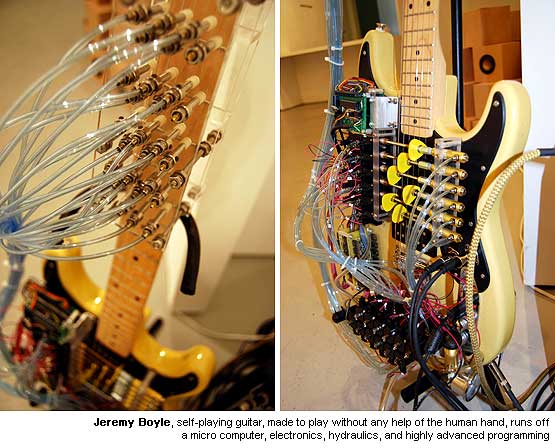

Jeremy’s work in the show, I think, can be viewed on a number of levels. But, for the most part I view it as an explanation of the ironies and idiosyncrasies of human behavior, as well as exploring the close relationship of process and creation. For example, his piece involving the large circular screen with the rotating projection, and the video on a rotating pedestal, both deal with similar ideas. The dichotomy that existed between the two pieces I thought was one of the most important of the show, and really embodied ideas reflected in a lot of the other pieces (more on these works below). It is these minute observations that Jeremy is able to delicately bring to the forefront and make obvious. Our human experience is under close scrutiny by Jeremy Boyle, and I think his art will tell you that. Jeremy’s sound pieces also seem to illustrate a certain form of dissection and re-contextualization. Since the gallery was so packed, it was hard to hear the white and brown noise pieces, but I felt that their relationship existed similarly to that of the two video pieces. The machine drawings on the walls were something that I never was able to see the actual construction of, nor had I seen the devices that created them. It seemed unimportant to me because I have seen how Jeremy works, and the work around the drawings explains them completely. The self-playing guitar (I think all of UMass has talked about his self playing guitar) was a manifestation of what Jeremy had been teaching our small independent study class about electronics. It is just so visually complex, and so actually complex, it nearly exists in another realm of understanding. It becomes for me something very different than a guitar.

Jeremy’s work in the show, I think, can be viewed on a number of levels. But, for the most part I view it as an explanation of the ironies and idiosyncrasies of human behavior, as well as exploring the close relationship of process and creation. For example, his piece involving the large circular screen with the rotating projection, and the video on a rotating pedestal, both deal with similar ideas. The dichotomy that existed between the two pieces I thought was one of the most important of the show, and really embodied ideas reflected in a lot of the other pieces (more on these works below). It is these minute observations that Jeremy is able to delicately bring to the forefront and make obvious. Our human experience is under close scrutiny by Jeremy Boyle, and I think his art will tell you that. Jeremy’s sound pieces also seem to illustrate a certain form of dissection and re-contextualization. Since the gallery was so packed, it was hard to hear the white and brown noise pieces, but I felt that their relationship existed similarly to that of the two video pieces. The machine drawings on the walls were something that I never was able to see the actual construction of, nor had I seen the devices that created them. It seemed unimportant to me because I have seen how Jeremy works, and the work around the drawings explains them completely. The self-playing guitar (I think all of UMass has talked about his self playing guitar) was a manifestation of what Jeremy had been teaching our small independent study class about electronics. It is just so visually complex, and so actually complex, it nearly exists in another realm of understanding. It becomes for me something very different than a guitar.

Jeremy was able to show a lot of brand new, and newly refurbished work in this show, and individual pieces are situated in ways that help individual pieces complement each other in interesting ways. For instance, as viewers enter the gallery space, they immediately encounter a large circular construction that is hung from the ceiling screen (one layer of Spackle, one layer of primer, two top coats) at eye level. Projected on the inside of this circle is a digital image of Jeremy’s head. The image of Jeremy’s head rotates around the inside of the circle. Similarly, nearby, there is another video piece involv

ing rotation. In this case it is a video that stands on a rotating pedestal, with again another rotating image.

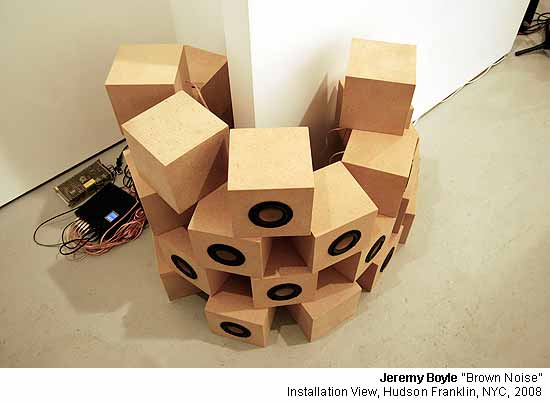

In two corners of the room were some of Jeremy’s sound pieces, one being White Noise, and the other Brown Noise. The white noise boxes (which I worked on) were approximately 3″ x 3″ inch white cubes, some with speakers in them and some without, all stacked on top of each other in a pile. The piece emits a soft hum of “white noise.” Nearby was the similar Brown Noise piece, made of brown boxes a little bit larger (about 6″ x 6″) arranged in the same manner and form as White Noise. Finally, Jeremy’s self-playing guitar, a complex electronically based instrument made to play without any help of the human hand, and instead running off a micro computer, electronics, hydraulics, and a lot of highly advanced programming.

In two corners of the room were some of Jeremy’s sound pieces, one being White Noise, and the other Brown Noise. The white noise boxes (which I worked on) were approximately 3″ x 3″ inch white cubes, some with speakers in them and some without, all stacked on top of each other in a pile. The piece emits a soft hum of “white noise.” Nearby was the similar Brown Noise piece, made of brown boxes a little bit larger (about 6″ x 6″) arranged in the same manner and form as White Noise. Finally, Jeremy’s self-playing guitar, a complex electronically based instrument made to play without any help of the human hand, and instead running off a micro computer, electronics, hydraulics, and a lot of highly advanced programming.

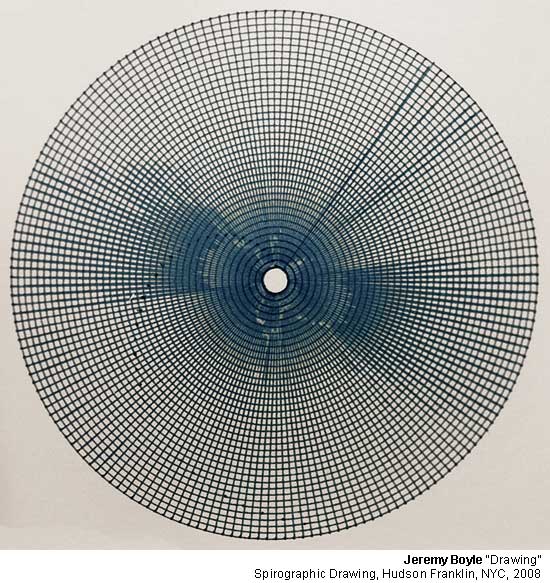

The machine drawings were one of the pieces that I was most excited about. Although I played no role in their construction, nor did I actually ever see them being made, I found them to be deeply compelling images. The complex images rendered by Jeremy’s hand-made machines seemed to fit perfectly with his other pieces that showed some of his elaborate electronic handiwork, such as the self-playing guitar. I find the idea of removing the artist’s hand almost completely from the final product, and really having the artist’s role exist behind the scenes a compelling idea. Upon closer inspection these machine drawings, done in a surprisingly simple ballpoint pen, have their imperfections. The process did not produce perfect drawings, but it was these mistakes that really drew me to them. Seeing the areas where the pen began to run out of ink were the most aesthetically pleasing, and the most interesting, as the flaws in even a mechanical design are exposed.

Jeremy’s large wall Spirograph seems to play off of Jeremy’s use of machines as well, although in this case the artist’s hand is visible, and the machine is instead just a facilitator. Rather than in the machine drawings, this Spirograph just literally guides Jeremy’s hand to make the pattern. In this case, there is a closer connection between the artist and his materials and final product. On another level, the Spirograph hints at a certain youthful vigor that Jeremy seems to occasionally play off of within his work. This can also be seen in his use of the ballpoint pen, often in my case associated with school-book scribbles and haphazard note taking. But, upon closer inspection of what the Spirograph really is (a series of gears within gears that creates mathematical curves in a very specific manner) you are able to see where the connections in Jeremy’s work begin to be made.

Jeremy’s large wall Spirograph seems to play off of Jeremy’s use of machines as well, although in this case the artist’s hand is visible, and the machine is instead just a facilitator. Rather than in the machine drawings, this Spirograph just literally guides Jeremy’s hand to make the pattern. In this case, there is a closer connection between the artist and his materials and final product. On another level, the Spirograph hints at a certain youthful vigor that Jeremy seems to occasionally play off of within his work. This can also be seen in his use of the ballpoint pen, often in my case associated with school-book scribbles and haphazard note taking. But, upon closer inspection of what the Spirograph really is (a series of gears within gears that creates mathematical curves in a very specific manner) you are able to see where the connections in Jeremy’s work begin to be made.

Finally, a piece that I have grown to know and love, whether it be because of my role in its production or its simple genius, is White Noise. I have found a place in my heart for this piece. “White noise” by definition is a signal with equal power across all frequencies. Jeremy’s piece was approximately 250 small boxes stacked on top of each other, some with speaker playing a level of white noise out of them. In this piece Jeremy actually provides a physical representation of sound, while including the sound that is being represented. Although during the opening the white noise was hard to hear coming out of the speakers (unless your ear was directly against them), I had heard them previously and the actual white noise that emits is quite interesting. It is a short of high hiss sound. This piece is accompanied almost directly across the room by the Brown Noise piece, and this created an interesting relationship within the gallery. The two pieces were speaking to each other in their different pure forms of sound, carrying on a kind of conversation. The literal stacking of the boxes creates an almost post minimalism take on sound. The White Noise and Brown Noise pieces both literally and figuratively converse with each other, describing an arena where audio landscapes are transcribed into physical realizations, thus providing. Similarly, the Spirograph wall drawing, and the machine made drawing also hold a dialog which suggests a distinct relationship between creator and creation, as well as the imperfections of not only the human hand, but also the machines.

After the show I felt a bit of remorse, knowing there would be no more topcoats to put on, no more boxes to sand, and no more Morrissey playing in a dusty studio. But from those days I spent in Jeremy’s studio, and from the time I spent with him in the classroom, I have learned a great deal not only about art, the art world outside of college, but also life itself. Jeremy Boyle works hard, he works very hard, and it shows not only in his show at Hudson Franklin Gallery (which I think was a tremendous success), but also in his students’ loyalty and dedication to his teaching. Jeremy does not gain respect from his students by being loud, or by enforcing rules and deadlines. Jeremy gains a students’ respect by being a teacher, by being kind and generous, and by doing what he does best: creating amazing art.

After the show I felt a bit of remorse, knowing there would be no more topcoats to put on, no more boxes to sand, and no more Morrissey playing in a dusty studio. But from those days I spent in Jeremy’s studio, and from the time I spent with him in the classroom, I have learned a great deal not only about art, the art world outside of college, but also life itself. Jeremy Boyle works hard, he works very hard, and it shows not only in his show at Hudson Franklin Gallery (which I think was a tremendous success), but also in his students’ loyalty and dedication to his teaching. Jeremy does not gain respect from his students by being loud, or by enforcing rules and deadlines. Jeremy gains a students’ respect by being a teacher, by being kind and generous, and by doing what he does best: creating amazing art.

In the end I am constantly left questioning whether my college experience, and my parents hard-earned dollars, are worth a BFA, which in my mind really means nothing. I think often of a philosophy student. A philosophy student is taught philosophy, only in most cases to become a philosophy teacher, thus creating a static cycle. But there is always that one Nietzsche, or that one Marx. Similarly, this is true for the art world. It is not really about the diploma, or AP portfolio, but instead it is about working hard for what you want. College is merely a way to facilitate that. Jeremy’s show at Hudson Franklin is a manifestation of what I am working for during these four years, and I will be eternally grateful to him for showing me that.

-Nicholas Sullivan

Born in Pittsburgh in 1975, artist/musician Jeremy Boyle received his BFA from the University of Illinois at Chicago and MFA from the Ohio State University. He was a founding member of the Chicago group Joan of Arc and has performed music (both solo and collaborative) extensively throughout the United States, Canada, and Japan and his recordings are internationally distributed. He has exhibited artwork, most of which is sound and technology based, in major cities across the U.S. including Chicago, New York, Los Angeles, Boston, Sacramento, Seattle,Miami, and Pittsburgh. he was awarded the PA Council on the Arts Fellowship in 2003, received the Heinz Creative Heights Award and completed a residency at the Mattress Factory in 2004, and received a Sprout Fund Seed Award in 2005-6. Recent projects include the completion of a public artwork commissioned by the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership and the Heinz Endowment in collaboration with architect Gerard Damiani and a solo exhibition at the Hudson Franklin Gallery in New York City. he is currently an Assistant Professor of Art at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. His work has been most recently seen at Deadtech in Chicago, IL, and at a mini-tour of performances last fall featuring his (self- playing) guitar and drums. Also in 2007, Boyle created the score for Jennifer Reeder’s first feature film, “Accidents at Home and How They Happen,” which premiered at the Wex ner Center for the Arts in Columbus, OH, on March 1. This is his third solo show with Hudson Franklin.

Nicholas Sullivan is an emerging artist completing a degree at UMASS Amherst where he has studied closely with and worked as assistant to artist Jeremy Boyle.

Hudson Franklin Gallery, 508 W 26th St., NYC, was established by Nicole Francis, a graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago’s MA program in Art History. Artists at Hudson Franklin includ Michael Bernstein, Jeremy Boyle, Jesse Chapman, Martin Esteves, Peter Fagundo, Alice Konitz, Elizabeth Saveri, Genevieve Walshe