Monday, June 21st, 2010

Creative Sparks – Brooklyn

Inside The Artist’s Studio

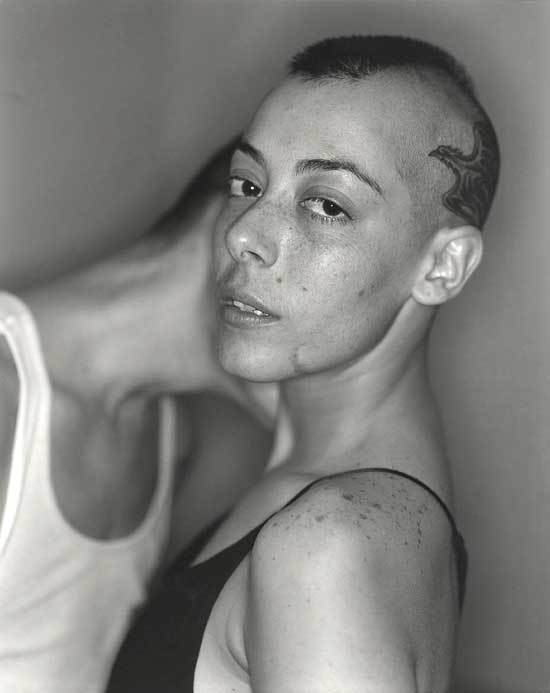

Ted Partin, San Francisco I, 2004

by Eva Mantell

Seeking creative sparks to flick at the doldrums. As always, I want to overdeliver the art goods as I’m defensive about the subject, particularly in front of a general audience. I start from the idea that you, at your core, suspect that most contemporary art is a con. Correct me if I’m wrong. I put in another idea — that you think the very best art is unattainable, practiced by only a few anointed ones, probably long dead, off limits to mortals. A secret practice whose essence can’t be cracked by the clumsy viewer. Whose talent is God-given. Somewhere in between the con and the holy is where I see the best contemporary art and I want to share it with you as directly as possible, and gather some creative sparks for myself in the process. If I bring you inside the artist’s studio you can observe this all firsthand. You’ll be able to see work informally, pinned to the walls, under consideration, unframed, in a jumble. You will be able to ask the artists anything you want. You’ll be able to get up close to art and see what, if anything, happens to you in the process.

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2006

The Creative Sparks tour, another in the depARTures series, takes off from the Arts Council of Princeton. I must say Route 1, the Turnpike and the Verrazano are looking good this morning. Free, clear and almost picturesque, the highways draw us straight to Gowanus, Brooklyn into the courtyard of the Old American Can Factory, and into a really choice parking spot, which frankly makes all seem right with the world. This could be a fine day. Our first meeting is with Diana Cooper, maker of improvised, energetic installations, and she greets us at the door to her studio in her personalized denim work apron. She gets right down to business and shares her project at Jerome Parker High School in Staten Island with us. Cooper remains open, amused and confident as she lets us in on the paradoxically bureaucratic process behind her loose and improvised installation piece: the paperwork, the budget, the haggling, the hours, the travel, including trips to Germany to work with the glass manufacturer, the stories about the teasing workman and the offhand comments made by the students themselves. The piece itself is decentralized, geometrically lumpy, made mostly from zigs and zags bisecting an almost chapel-like series of blue glass windows. Looking around the studio I see a line, in this project and in others: a line that is an energetic, protean little bugger. It can be two or three dimensional. It can turn, wrap around, radiate, droop, about face, streak. The line can mass, reproduce and in increments it builds systems, cities and odd worlds. Cooper has written about playing with that line: “doodling is, I think, an expression of the unconscious, it sometimes captures inner connections and becomes, in its way, a system. Conversely, we might think of some of the graphic systems we are familiar with as society’s unconscious doodling.”

Diana Cooper “Out of the Corner of My Eye,” 2009, 11 ft x 110 ft x 6 in

Wood, MDF, glass, acrylic, epoxy and Nida-Core

Permanent Installation, Jerome Parker Campus, Staten Island, NY

Cooper is a conscientious about her unconscious, and doodles her way into some lovely art situations. Materials like bits of plastic, tubes, pompoms and other stuff that seems just barely dimensional join the parade, accreting into installations that come to look almost like a kind of chunky expanded painting…as much as things project they remain hovering over the walls and floor, relating to the surface planes of paintings. Her colors are very stark and very organized: the high school installation is mainly blues; here in the studio is a wall of photography and ephemera that is mostly orange. Another project is pink and green. It’s a system where all elements are knowable, all colors are knowable. It’s like seeing the ingredients and what comes out of the oven simultaneously. I get the energy, play, connections, and the continuous act of keeping going.

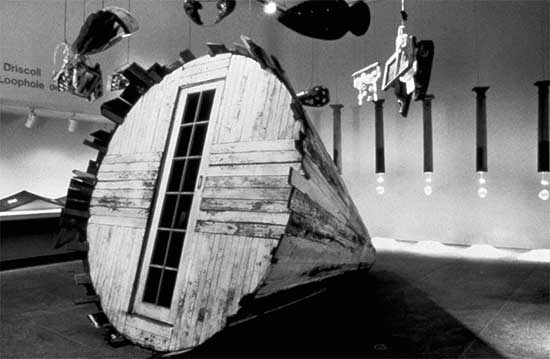

Ellen Driscoll “The Loophole of Retreat,” 1991

We walk upstairs and meet Ellen Driscoll, a ridiculously accomplished woman who chairs the sculpture department at RISD, and has permanent installations up and down the country, including one in the subway at Grand Central. I first saw her work in the ’80’s as a student, so I come to her as a fan, with great curiosity about how it all happens. She greets us with a curiosity about us too, how we live, what we teach, how our lives are put together. Her early works had a hand-made, hand-hewn, historic and literary feel that I have always loved. A linear quality with silhouettes as shadows in stereoscopic projections, with some chunky wooden parts, simple machines. 19th Century literature and history and tragedy. She connected through her process to another time, through piecework, through women’s work, through laborer’s work, to bring out narratives that might have been lost.

Ellen Driscoll “FastForwardFossil; Part 2,” 2009,

installation view, gathered water bottles, glue

In her studio today her realm is now the future, looking back on the present. The material is found plastic, discomforting and piquing. At ankle height are sections of a miniature dystopian landscape made entirely from those clouded plastic water jugs that Driscoll has collected in a kind of daily penitent’s tour of neighborhood garbage cans. The jugs, now transformed into surprisingly hard-edged geometric shapes, become child-like tableaus of the oil industry and a ravaged environment, with miniature derricks, scaffolds, fallen trees and toppled houses. The reclaimed plastic looks milky and translucent, appealing but perilously so as we know it embodies the story of fossil fuel pollution. The appealing playfulness of the piece combined with its finite message roils me.

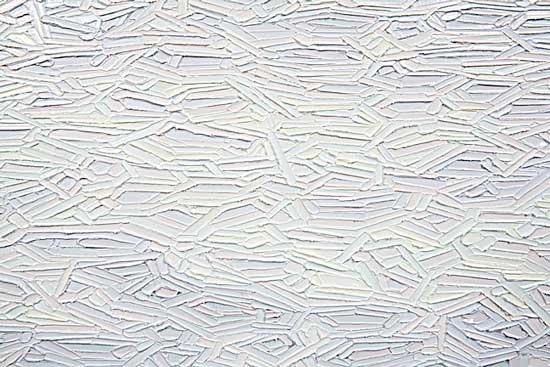

Stuart Elster “White Head,” 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

On the walls are drawings, in blue and black ink, with spills and stains, structures of industry, steel, stairways, memories of certain kinds of dead ends. She unrolls and unfolds walnut oil paintings, with spills and reactions, architectural and sweeping horizontal views of tortured landscapes. There’s a feeling of Romantic ruins, awkward, as I don’t know where to put the beauty and longing I feel in the overall picture of human failure. What to do? Document our failures? Find our place in it? Find our reason to keep going? Our meeting with Driscoll is surprisingly intimate, and it seems the larger questions raised are not going away any time soon.

Stuart Elster “White Head,” Detail, 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

Things can begin to look a little stark when the blood sugar drops, so maybe we better grab lunch. We go to Ici, on Dekalb, and the small restaurant we step down into, through the felt curtain, is organic, tasty, and seems to hit the spot (except I’m still hungry). As we drive to Long Island City to see Stuart Elster, I ought to eat the take-out muffins I ordered, but I get distracted, so they stay on the floor of the van in a white paper bag. Best to be a bit on edge.

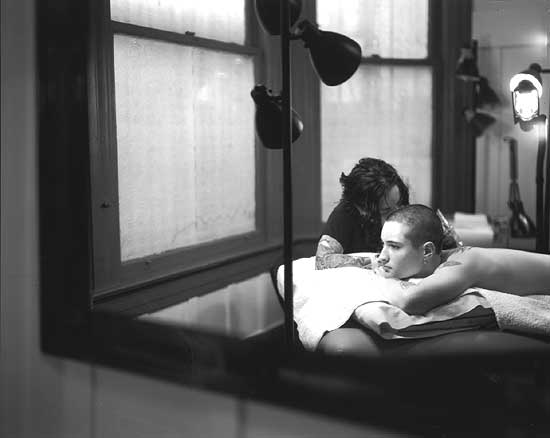

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2009

Elster is devoted, intense, pleasantly on edge himself. His paintings are almost excruciatingly conceptual, to the point where I think they must be unphotographable, that’s how specific they are, how untranslatable from themselves they are. He has taken the humble copper penny as his subject, but his paintings depart quickly from coins, symbols or signs, though if directed by Elster I can see Abe Lincoln’s profile if I squint just right here or there. The paintings are about a painter painting paintings with paint. Think of Seurat, Ad Reinhardt and Jasper Johns with their eyes closed, their minds not being able to shut off making a painting. The practice of painting is offered up as microscopic moments of application, brushstrokes dissected, the rainbow stripped and exposed. Before us is paint, are colors, optics and a physicality so that each brushstroke’s highlights and shadows are scrutinizable too. A strange bonus, these works can be viewed with the lights on or with the lights off and they will perform for you either way. So naked are these canvasses in their conceptuality I think they are in need of an art critic to dress them in language and in theory! I look forward to a show of these works, and here’s hoping I’ll be able to understand the essay that goes with it.

Ted Partin, San Francisco II, 2004

Down the hall we come to Ted Partin’s photography studio. Partin is earnest and open with us, spreading out the photos he has been printing. It’s rare to be near unframed, classic photographs, and to see their scale and sheen. Nothing digital here. In the quiet space of this kind of art (no surveillance cameras, no music, no soundtrack, no interaction) we can stare. Partin stages his large-format black and white portraits knowing that we expect them not to be staged, but as voyeurs, we’re happy to look either way. Here’s an anthropology museum of people and things to look at and then keep looking at. Ambiguity rules the day, as place, gender and ethnicities seem unknowable; as if, if we knew, we’d possess these people, these situations, fully. Their beauty and longing seems real enough. Their sense of themselves seems real enough. Stare away. In the meantime the world has changed. And changed again.

Eva Mantell

originated June 21, 2010