Friday, December 10th, 2010

Humanism of the automated other;

or reading Baruch Gottlieb’s i-Mine1

Wii Controller To Activate

Jeremy Fernando

This ‘beyond’ from which the face comes and that sets consciousness in its rectitude, is it not in turn an unveiled understood idea?

(Emmanuel Levinas, Humanism of the Other: 38)

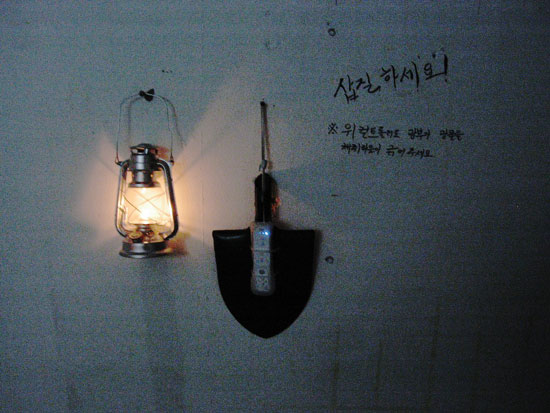

Stepping into the Second Order (http://www.secondorder.kr/) exhibition at Space Hamilton, Seoul (http://spacehamilton.com/), one is struck by the fact that one is not in a gallery-it is, as its name invokes, a space. Here, one can all too easily hear notions of the openness needed for though, action even; extending perhaps to calls for interventions. And there is nothing at Space Hamilton itself to deny that gesture-walking in during a freezing Wednesday evening, 8 December, 2010, one is hit with a final frontier of sorts.

This physical discomfort though pales in comparison with the encounter that Baruch Gottlieb opens with his work i-Mine: it is a drop into a cold, yet invigorating, stream of Kierkegaardian absurdity.2 In adopting, naming, and being, an avatar whose sole role is to mine for minerals fast enough to keep overall prices down, whilst slow enough for them to maintain a minimal level, one also has to contend with a soldier that is awaiting any opportunity to steal from you, and who inevitable shoots you-one cannot win at this game; one can only stay alive, awhile longer. This is a game-there are exact rules to staying alive-where death confronts you, is staring at you, is always already with you; perhaps only not just yet.

Audience Playing i-Mines On

A question that Gottlieb faced throughout the opening, and later at a dialogue session on Saturday, 11 December, was whether a game, at an exhibition at that, was an appropriate venue for a meditation on the death, and life-hours, of people that are inscribed in all technology. Perhaps here, if we listen carefully, we can hear Lenin’s eternal question echoing in the background: that of “what is to be done?” After all, a question of relevance is almost always also a question of ‘what can we do about it; how can we change the situation’. And like any self respecting artist, Gottlieb is holding up a mirror to society, and thus in a way is also bringing down the question on himself. To compound matters, by using technology to open his quest, Gottlieb exposes himself, opens his self to the scrutiny of those very same questions. However, what we must never forget is the notion of the quest in question-it is constantly moving, searching, probing, opening. In this way, perhaps what is to be done is precisely what is done-there are no prescriptions here. All we can do is attempt to hear; listen.

By exposing himself, his self, Gottlieb and his quest will always be haunted by this question. This is especially true as he positions this piece as part of a larger work which intends, attempts, to trace, and document, the echoes of human lives in all devices. And since a project of this magnitude can only be approached through computers, computing-and ultimately a calculating formula-the question of context, and whether natural lives and deaths can be thought through an artificial medium, resounds loudly.

But in this quest, we must not make the mistake of paying too much attention to the question; we must not allow the question to take over the quest. For, in every question, there is always already an echo of the meta hodos-the path over which we attempt to travel. It is not a random searching though: there is a method, a way, a strategy, even though the ending is never known, perhaps until, or even after, it arrives. Hence, even as we quest, even in an attempt to respond to the question, we must never allow the question to determine the end-a teleology-of the quest. Thus, in some way, this question, like all questions, completely misses the point.

Playing the i-Mines Game

One can only attempt to respond to the other, to the other in her full otherness, whilst maintaining a gap, a space between one’s self and her. Otherwise, all one is doing is subsuming her under one’s self, consuming her-otherwise one is calling her i-mine. In order that the other remains fully other, one has to gaze at her, look even, but never claim to have seen her-her face must always already be veiled from us. The other must remain distant, foreign, unfamiliar-artificial.

And what better way to foreground this artificiality than at an exhibition-made even more disconcerting by the fact that the exploitation of human lives for mobile phones is played out on a mobile phone, by everyone who has one sitting snugly in their pocket, or bag.

Faced with that level of absurdity, it is all too tempting to echo Lear and tear out one’s hair in the storm. But that would be too easy, too convenient-a disavowal through excess, a momentarily release through madness.

What Gottlieb’s i-Mine forces us to confront is far worse.

Score Board For i-Mines Game

Violence, death, blood, is a very part of our existence, is what our lives-and the way we live-depend on. We can no longer complain about the barbaric sacrifices of the Aztecs so that the sun may rise again-at least they knew her name, her face, her story. All we are doing is offering deaths blindly, indiscriminately, randomly. This is not a sacrifice-there is no longer a God.

This is a shoah.

We would like to think that we have come far. The shiny objects that we use in our daily lives help with this illusion. Gottlieb shows us that all we are doing is hiding behind a screen.

Can you tell a green field from a cold steel rail?

A smile from a veil?

Do you think you can tell?

(Pink Floyd: Wish you were here)

*****

Jeremy Fernando is the Jean Baudrillard Fellow at the European Graduate School. He works in the intersections of literature, philosophy, and the media; and is the author of Reflections on (T)error, Reading Blindly, and The Suicide Bomber; and her gift of death. Exploring other media has brought him to film, music, and art; and his work has been shown in Seoul, Vienna, Singapore, and Hong Kong. He is the editor of thematic magazine One Imperative; and is also a Research Fellow at the Centre for Liberal Arts & Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University.

1 http://i-mine.org, the i-Mine apps for Android and iPhone, videos and related presentation materials were created by Baruch Gottlieb, Horacio González Diéguez and Cocomoya

2 One would expect the buzz from being awarded Design Capital of the World, 2010, to set Seoul’s art scene alight. Instead, one is confronted with a certain coldness, detachment, aloofness. But if we take into consideration the fact that what is foregrounded is creative production, then even as much as the claim is for diversity, culture, and design, this is always already a teleological premise; one directed towards performativity, productivity, product. And this is precisely why Gottlieb’s work is startling. For, even though it takes place in, and through, the medium of a mobile phone, it calls the very medium itself into question: a question that the quest for industrial design would like to leave veiled.