Creative Sparks – Brooklyn

Inside The Artist’s Studio

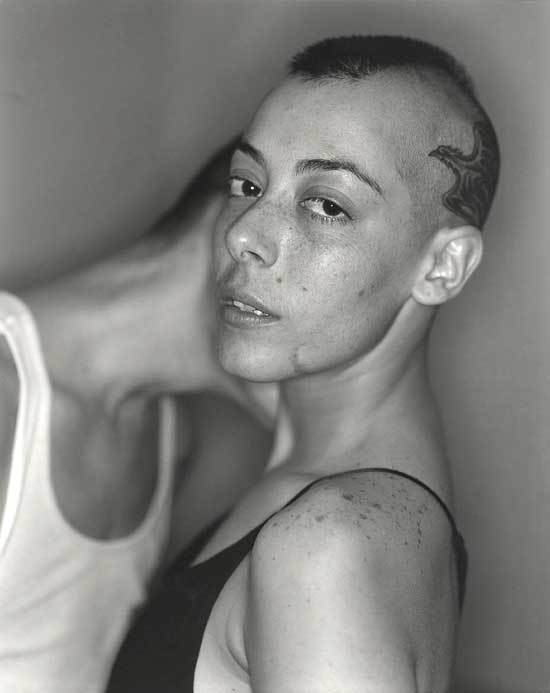

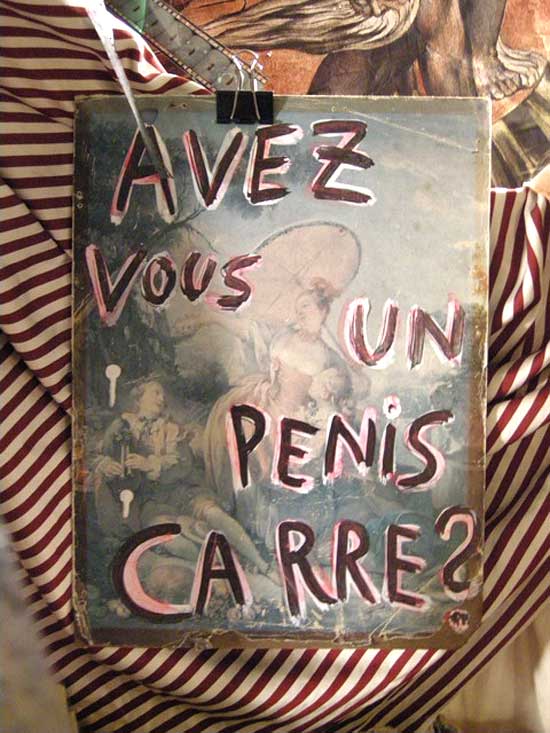

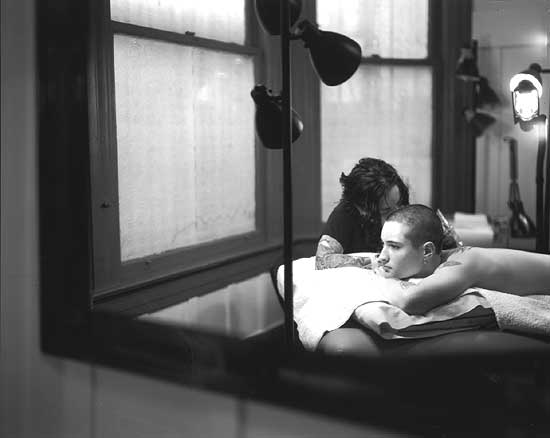

Ted Partin, San Francisco I, 2004

by Eva Mantell

Seeking creative sparks to flick at the doldrums. As always, I want to overdeliver the art goods as I’m defensive about the subject, particularly in front of a general audience. I start from the idea that you, at your core, suspect that most contemporary art is a con. Correct me if I’m wrong. I put in another idea — that you think the very best art is unattainable, practiced by only a few anointed ones, probably long dead, off limits to mortals. A secret practice whose essence can’t be cracked by the clumsy viewer. Whose talent is God-given. Somewhere in between the con and the holy is where I see the best contemporary art and I want to share it with you as directly as possible, and gather some creative sparks for myself in the process. If I bring you inside the artist’s studio you can observe this all firsthand. You’ll be able to see work informally, pinned to the walls, under consideration, unframed, in a jumble. You will be able to ask the artists anything you want. You’ll be able to get up close to art and see what, if anything, happens to you in the process.

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2006

The Creative Sparks tour, another in the depARTures series, takes off from the Arts Council of Princeton. I must say Route 1, the Turnpike and the Verrazano are looking good this morning. Free, clear and almost picturesque, the highways draw us straight to Gowanus, Brooklyn into the courtyard of the Old American Can Factory, and into a really choice parking spot, which frankly makes all seem right with the world. This could be a fine day. Our first meeting is with Diana Cooper, maker of improvised, energetic installations, and she greets us at the door to her studio in her personalized denim work apron. She gets right down to business and shares her project at Jerome Parker High School in Staten Island with us. Cooper remains open, amused and confident as she lets us in on the paradoxically bureaucratic process behind her loose and improvised installation piece: the paperwork, the budget, the haggling, the hours, the travel, including trips to Germany to work with the glass manufacturer, the stories about the teasing workman and the offhand comments made by the students themselves. The piece itself is decentralized, geometrically lumpy, made mostly from zigs and zags bisecting an almost chapel-like series of blue glass windows. Looking around the studio I see a line, in this project and in others: a line that is an energetic, protean little bugger. It can be two or three dimensional. It can turn, wrap around, radiate, droop, about face, streak. The line can mass, reproduce and in increments it builds systems, cities and odd worlds. Cooper has written about playing with that line: “doodling is, I think, an expression of the unconscious, it sometimes captures inner connections and becomes, in its way, a system. Conversely, we might think of some of the graphic systems we are familiar with as society’s unconscious doodling.”

Diana Cooper “Out of the Corner of My Eye,” 2009, 11 ft x 110 ft x 6 in

Wood, MDF, glass, acrylic, epoxy and Nida-Core

Permanent Installation, Jerome Parker Campus, Staten Island, NY

Cooper is a conscientious about her unconscious, and doodles her way into some lovely art situations. Materials like bits of plastic, tubes, pompoms and other stuff that seems just barely dimensional join the parade, accreting into installations that come to look almost like a kind of chunky expanded painting…as much as things project they remain hovering over the walls and floor, relating to the surface planes of paintings. Her colors are very stark and very organized: the high school installation is mainly blues; here in the studio is a wall of photography and ephemera that is mostly orange. Another project is pink and green. It’s a system where all elements are knowable, all colors are knowable. It’s like seeing the ingredients and what comes out of the oven simultaneously. I get the energy, play, connections, and the continuous act of keeping going.

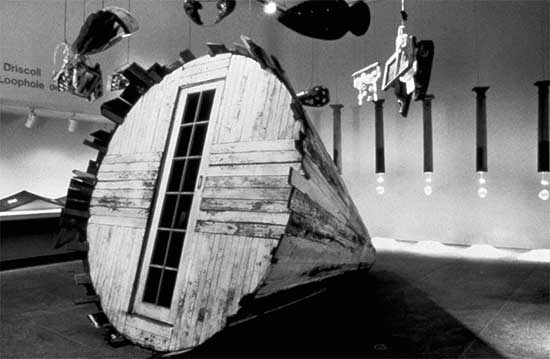

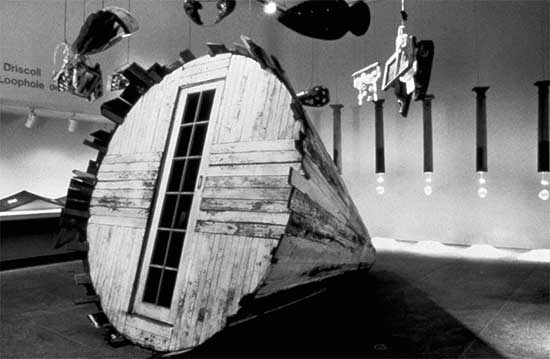

Ellen Driscoll “The Loophole of Retreat,” 1991

We walk upstairs and meet Ellen Driscoll, a ridiculously accomplished woman who chairs the sculpture department at RISD, and has permanent installations up and down the country, including one in the subway at Grand Central. I first saw her work in the ’80’s as a student, so I come to her as a fan, with great curiosity about how it all happens. She greets us with a curiosity about us too, how we live, what we teach, how our lives are put together. Her early works had a hand-made, hand-hewn, historic and literary feel that I have always loved. A linear quality with silhouettes as shadows in stereoscopic projections, with some chunky wooden parts, simple machines. 19th Century literature and history and tragedy. She connected through her process to another time, through piecework, through women’s work, through laborer’s work, to bring out narratives that might have been lost.

Ellen Driscoll “FastForwardFossil; Part 2,” 2009,

installation view, gathered water bottles, glue

In her studio today her realm is now the future, looking back on the present. The material is found plastic, discomforting and piquing. At ankle height are sections of a miniature dystopian landscape made entirely from those clouded plastic water jugs that Driscoll has collected in a kind of daily penitent’s tour of neighborhood garbage cans. The jugs, now transformed into surprisingly hard-edged geometric shapes, become child-like tableaus of the oil industry and a ravaged environment, with miniature derricks, scaffolds, fallen trees and toppled houses. The reclaimed plastic looks milky and translucent, appealing but perilously so as we know it embodies the story of fossil fuel pollution. The appealing playfulness of the piece combined with its finite message roils me.

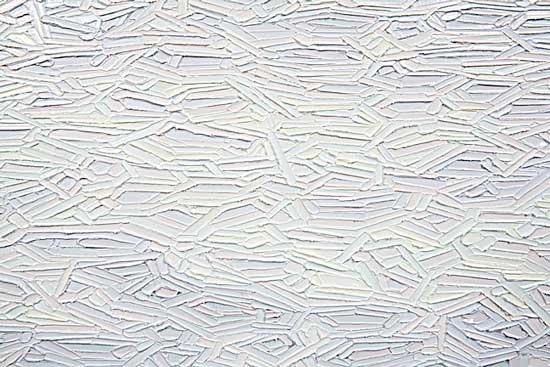

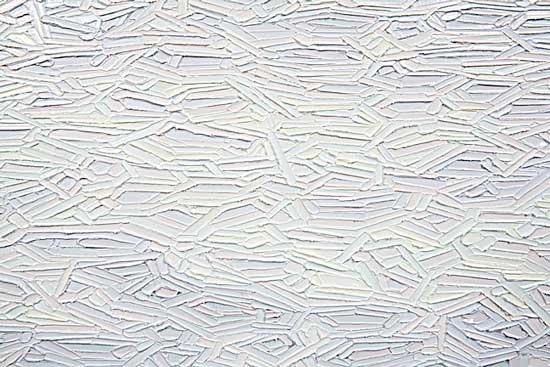

Stuart Elster “White Head,” 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

On the walls are drawings, in blue and black ink, with spills and stains, structures of industry, steel, stairways, memories of certain kinds of dead ends. She unrolls and unfolds walnut oil paintings, with spills and reactions, architectural and sweeping horizontal views of tortured landscapes. There’s a feeling of Romantic ruins, awkward, as I don’t know where to put the beauty and longing I feel in the overall picture of human failure. What to do? Document our failures? Find our place in it? Find our reason to keep going? Our meeting with Driscoll is surprisingly intimate, and it seems the larger questions raised are not going away any time soon.

Stuart Elster “White Head,” Detail, 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

Things can begin to look a little stark when the blood sugar drops, so maybe we better grab lunch. We go to Ici, on Dekalb, and the small restaurant we step down into, through the felt curtain, is organic, tasty, and seems to hit the spot (except I’m still hungry). As we drive to Long Island City to see Stuart Elster, I ought to eat the take-out muffins I ordered, but I get distracted, so they stay on the floor of the van in a white paper bag. Best to be a bit on edge.

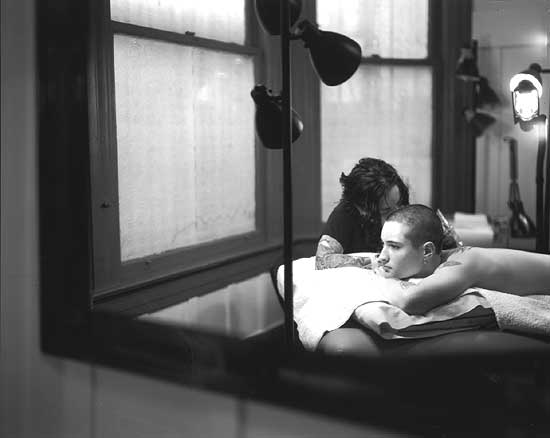

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2009

Elster is devoted, intense, pleasantly on edge himself. His paintings are almost excruciatingly conceptual, to the point where I think they must be unphotographable, that’s how specific they are, how untranslatable from themselves they are. He has taken the humble copper penny as his subject, but his paintings depart quickly from coins, symbols or signs, though if directed by Elster I can see Abe Lincoln’s profile if I squint just right here or there. The paintings are about a painter painting paintings with paint. Think of Seurat, Ad Reinhardt and Jasper Johns with their eyes closed, their minds not being able to shut off making a painting. The practice of painting is offered up as microscopic moments of application, brushstrokes dissected, the rainbow stripped and exposed. Before us is paint, are colors, optics and a physicality so that each brushstroke’s highlights and shadows are scrutinizable too. A strange bonus, these works can be viewed with the lights on or with the lights off and they will perform for you either way. So naked are these canvasses in their conceptuality I think they are in need of an art critic to dress them in language and in theory! I look forward to a show of these works, and here’s hoping I’ll be able to understand the essay that goes with it.

Ted Partin, San Francisco II, 2004

Down the hall we come to Ted Partin’s photography studio. Partin is earnest and open with us, spreading out the photos he has been printing. It’s rare to be near unframed, classic photographs, and to see their scale and sheen. Nothing digital here. In the quiet space of this kind of art (no surveillance cameras, no music, no soundtrack, no interaction) we can stare. Partin stages his large-format black and white portraits knowing that we expect them not to be staged, but as voyeurs, we’re happy to look either way. Here’s an anthropology museum of people and things to look at and then keep looking at. Ambiguity rules the day, as place, gender and ethnicities seem unknowable; as if, if we knew, we’d possess these people, these situations, fully. Their beauty and longing seems real enough. Their sense of themselves seems real enough. Stare away. In the meantime the world has changed. And changed again.

Eva Mantell

originated June 21, 2010

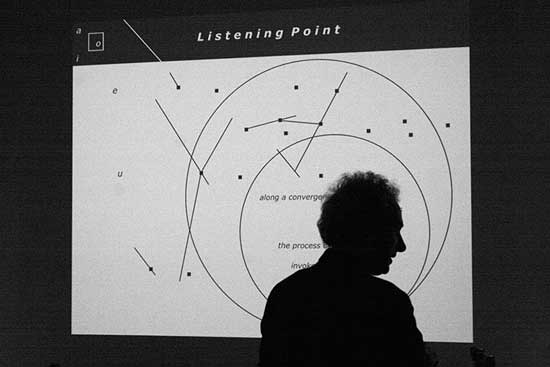

Mark Bloch at Emily Harvey Foundation

New York’s SoHo, 03-25-10

correspondence: in the Artists’ Voice

photography: Tom Warren for Mark Bloch

at Emily Harvey Foundation

The Art of Storàge

by Mark Bloch

Storàge is a new art form for our times in which artists will prevent at all costs, their work from seeing the light of day. Artists must conceal what they do, make sure no one finds out that they are brilliant. If an artist must show someone something they have created, they should show another artist so as not to upset the art markets. Other artists do not really count as human beings so there really is no harm in telling them. That is how art continues to thrive. Artists are sequestered from the rest of humanity. But one should proceed with caution because occasionally artists know actual people and the news of what kind of work the artists are producing must not spread to civilians.

Storàge is an art form like many others: collàge, assemblàge, frottàge. The accent is on the second syllable. The emphasis is on the storing of important information and objects–preferably one of a kind objects, although the storing of multiples is also encouraged–until a great deal of time has passed and the ideas and images contained therein, hidden from public view, have been discovered and explored by other, less talented individuals. This is bound to happen while the work is rotting under lock and key, no matter how advanced the work. Even the most vanguard artist will be unable to stave off the advancing future which will soon provide the unique conditions necessary for the artist’s work to be removed from Storàge without consequence.

Once a work of art has been rendered culturally feckless, Storàge is no longer necessary. The work can now be trotted out into the marketplace where it will no doubt have to endure other types of packaging, wrapping and covering which are part of the Storàge process when enacted by a Storàgist but in these new contexts the accent in Storàge is removed and it becomes simply storage in which excessive packaging and hygienic germ free protection is always considered good for business. Of course any work of art or other consumer item, no matter how processed and “valuable,” always remains in danger of being placed on dusty shelves in the forgotten back rooms of galleries or museums by art professionals. This is where the nuances of Storàge and storage are revealed–for it is these very art professionals who are uniquely qualified to determine whether or not an artist’s work is any good. During the interim period when the artists are left trying to make this crucial decision for themselves, their work must be safely hidden from view while these art professionals are courted at the artist’s expense without causing too much of a fuss, for it is the artist’s passion that must also remain in the limbo of Storàge, not just their output.

Sometimes fear of the art professionals will cause an insecure artist, one prone to alarmism and in constant dread of being accused of being labeled an exhibitionist, to send works into hiding early, thus risking beginning their career as a Storàge Artist prematurely. But there is nothing to be alarmed about here. Fears about these types of fear are only a waste of time. Any uncertainty at all must always be acted on immediately. To err on the side of invisibility is never a mistake. If an artist has any doubts at all about the worthiness of what has been created, they should simply place the work in a secure area, free from intellectually curious intruders where no one can see it. In fact experience has shown that no work is too ripe to entertain misgivings about its readiness for public consumption. Any suspicions at all should be indulged whole-heartedly and enthusiastically by the Storàge Artist.

Mark Bloch

More on The Art of Storage (.pdf)

The Art of Storage was recently seen as part of Mark Bloch’s one man show “Secrets of the Ancient 20th Century Gamers” at Emily Harvey Foundation in NYC March 18 through April 2.

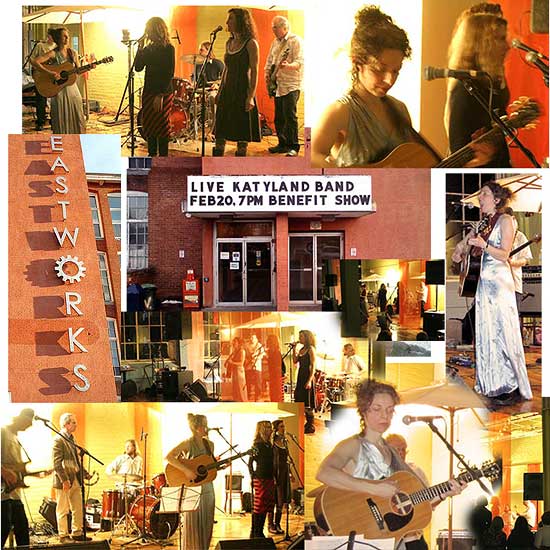

NEW WORKS • NEW VIEWS • NEW MINDS: Stage One: KATYLAND live at Artist Organized Art Benefit Launch

by Jessica Higgins and Erika Knerr

photography: Denis Luzuriaga

Participating artists: Aimee Xenou, Alicia Renadette, Andy Laties, Andrew Greto, Ann Lewis, Barbara Neulinger, Beth Lawrence, Carl Caivano, Christin Couture, Christine Tarantino, Christopher Blair, Dave Gloman, Dean Nimmer, John Landino, Denis Luzuriaga, Dwight Pogue, Erika Knerr, Fletcher Smith, Jessica Higgins, John Romanski, Joshua Selman, Kathleen Trestka, Katie Richardson, Katy Schneider, Laurie Goddard, Maggie Nowinski, Matt Anderson, Matt Anderson, Nancy Natale, Ninette Rothmüller, Pablo Yglesias, Rosa Guerra, Sarah Valeri, Sue Katz, Susannah Auferoth, Tracey Physioc Brockett, William Hosie, Luzuriaga video includes Ursonate Urchestra

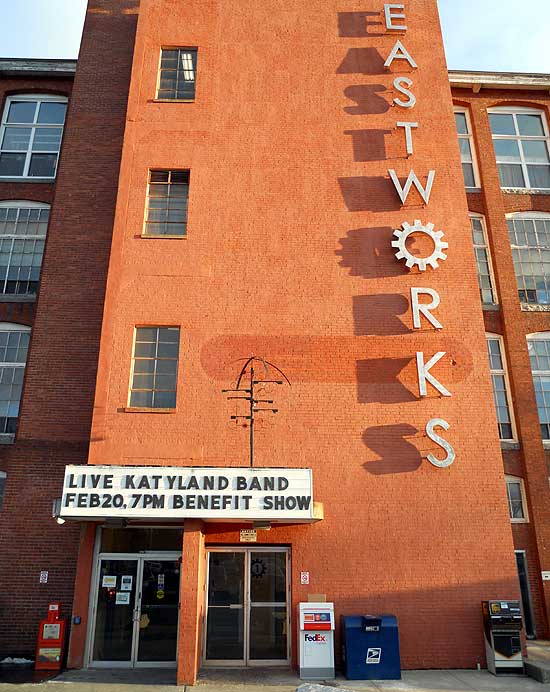

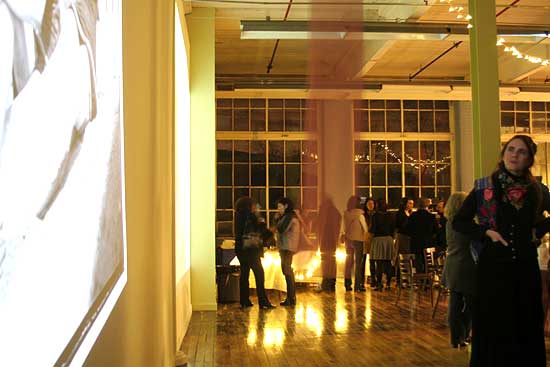

February 20th was an auspicious date for the arts community! That Saturday night, was the first of three parties to benefit Artist Organized Art in which A.O.A. threw a community outreach event, arts network builder, exhibition, performance…did I forget to say fundraiser?

Northampton’s Katy Schneider, a guitarist, singer, songwriter and painter, accompanied by Julie Starr and Caitlin Bosco on back up vocals, Jason Smith on drums and Bruce Mandaro on guitar and mandolin. http://www.myspace.com/katyschneider. Also see Katy’s work at www.katyschneider.com

The event featured large projected images by local artists of the Pioneer Valley in Massachusetts and hard and soft indie music by Katyland along with some great cover songs, a regional progressive music favorite.

Denis Luzuriaga, a painter and video artist, compiled the projected images: in the dead of winter the crowd was treated to a colorful array of visual artworks, documents and pleasantly dated black and white photos of beach scenes.

le=”text-align: justify;”>The overall effect; “a swirling sound stretched out on the night with projections of art interfacing the viewers” Jessica Higgins

Each element of the event reflected a key component of the AOA mission to support creative independence in the form of self-supporting and self-generating exhibitions through artist organized media, events and cultural education.

The festivities took place at Eastworks a converted warehouse on the river at 116 Pleasant Street in Easthampton. Artists of all kinds and their allies came from neighboring towns as well as the studio and residential community of Eastworks, a loft building community founded by Will Bundy.

The social and experimental quality of the event recalled important artist communities associated with the avant-garde: Black Mountain College during the 1940s and 1950s, the Village and SoHo in the 1960s and 1970s, and California in the 1970s and 1980s. Why not Massachusetts as an internet hub brought together by AOA in the 2010s?

The event represents a significant group effort organized by artists: Susannah Auferoth, Jessica Higgins, Erika Knerr (also representing New Observations, the seminal New York arts magazine that was recently acquired by AOA), Denis Luzuriaga and Joshua Selman. Artist Organized Art is working to improve the quality of life through community culture.

The event isn’t over yet. If you were there and have pictures of the event, send them in to be a part of the record! If the event sounds like fun and you’re bummed you missed it, keep your eyes out for more. AOA is ever eventful.

The success of A.O.A. comes from community support (cultural, logistical and financial), which means everyone is invited to be apart of it, enriching our world by organizing its culture as artists. Benefit parties for Stage Two and Stage Three will be forthcoming.

FREESPACE IN THE CITY OF LIGHTSFreespace Exhibition and Performances

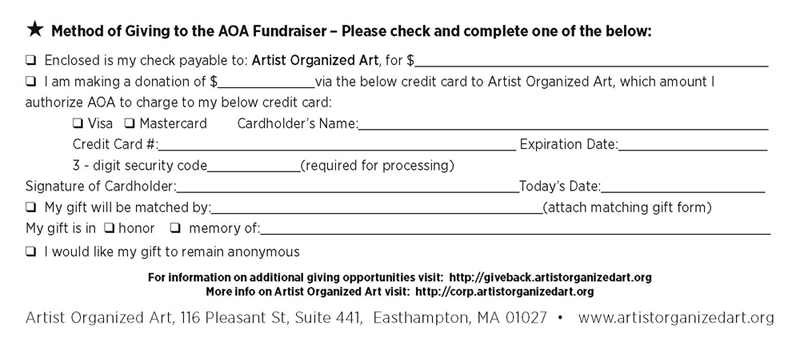

59 Rivoli Aftersquat, Paris, December ‘09‘Do you have a square penis?’ By Swiss-Morrocan

Paris correspondent, participant artist, Angie Eng

The romantic vision of the artist in his solitude, poverty-stricken, hyper-intelligent delusional world, the tabloid reader may even imagine him living and working in a graffitied, Lower East Side 80’s freezing cold moldy squat next to the crack queue. Those were the days, they say… before the real estate boom and diamond skulls. Don’t panic, there are still freezing cold, stinky albeit renovated spaces to produce art for little or no rent (in Paris, that is.) Last December (In the aftermath I refer to as my ‘temporary creative masochistic state’) I plunged myself into heading two weeks of artist organized art in a former squat in Paris.

To rebel against the Christmas consumer rush on Rue de Rivoli, I recruited my most faithful to help run Freespace a series of free concerts, performances, readings and an exhibition based on the theme of public space.

Even though this is rumoured to be the 3rd most visited cultural venue in Paris, I stumbled upon it during an artist tour, 2 weeks after its re-opening as an official, legal space for artists to work and play. This 6-story building sandwiched between the Louvre and Hotel de Ville, includes a dazzling storefront gallery space, 30 open artist studios and a micromuseum. I have to admit my original intent was not to organize a series of art events, but to do a site specific window installation of a faux travel agency selling public space. My arm was twisted and it had been a while since I organized some art events. Et voilà…

Freespace Exhibition and Performances December 8-20, 2009, 59 Rivoli Aftersquat, Paris

Participating artists: A-li-ce, Cecile Babiole, Luc Barrovecchio, Christiane Blanc, Nina Canal, Steve Dalachinsky, Angie Eng, Elizabeth Gilly, HeHe (Helen Evans, Heiko Hansen), Kentaro, Stuart Krusee, Cecile Le Combe, Les hautsdeplafond (Pierre Lutic & Philippe Gautier), Thierry Madiot, Agathe Max, Mectoob, Yuko Otomo, Margarita Papazoglou, Plectrum, Claude Parle, Atau Tanaka

Grace à the city of Paris, the former Bank of Lyon known as Chez Robert on 59 Rivoli was ‘regulated’ and renovated after years of squatter status. Listen to the interview with Swiss-Morrocan one of the head chiefs of the ‘Aftersquat’.

After my eye-opening experience with 59 Rivoli Aftersquat, I decided I would write this article and do a Q/A with 2 other artist run spaces where I had presented work in the last year: La Générale en Manufacture, Sèvres and Les Voutes (affiliated with Les Frigos). I found it would be impossible and almost suicidal to make my own art and even fathom running an artist run place all year round. These artist/organizers are definitely a special breed, a rare species in a time when the collective body decomposed decades ago.

All three spaces are artist collective run, currently government owned, legalized spaces for artists to work and organize events and artists’ residencies. All of them pay for electricity, insurance, water. (In some cases, ‘rent’ and also former collective debts from either unpaid utility bills or renovations) Although they share a similar paradigm of alternative art space, each is unique in their intent and vision of being on the periphery or even outside the inside art world.

I consider Les Voutes to be one of the more beautiful places to make art in Paris, 59 Rivoli to be run by the most friendly and unpretentious artists I’ve ever met and La Générale en Manufacture at Sèvres too new to say NO.

On the side, France still has one of the largest cultural art budgets in the world (2.8 billion in 2009 or $622 per person per year). By the way, the 2009 NEA cultural arts budget in America was 265 million or 86 cents per person per year. However, politics and administration goes hand in hand with government funding. In France, wanting a piece of that pie, artists are suggested to create associations or mini-non profit organizations, sign contracts abiding by city legislation and regulations in order to plan their artistic activities around ‘festivals.’ Count the logos at the bottom of the invites to get an idea of the size of each slice. With these fig

ures, doing independent events 100% artist run in government owned buildings, is to put it frankly, an illusion. Be that as it may, I’m grateful that these spaces exist grace à the Ville de Paris and have not been burned down or sold to luxury housing developments like the City of New York. I’m still not sure if larger cultural budgets change the quality of art, but we can all agree its better to have more than less in the diffusion of cultural practice.

“In my opinion, the art market is a dead donkey covered with flies.

It’s made for a bunch of rich happy few.

We always see the same ridiculous official artists

promoted through these kind of private circles

with no hope of seeing something new…

We do not want to be a part of this private joke.

We expect nothing from others

(governement, official organizations, etc.)

We do what we have to and want to do.”

-Pierre Wayser, Les Voutes

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Les Voutes, photo by Pierre Wayser

Building: 19 rue des Frigos 4 underground train tunnels approximately 1000 sq feet each and a garden

Established: 1998

Owner: former owner was SNCF then, le Réseau Ferré and then City of Paris since 2003

Regulated: 2000

Purpose: ‘We decide to create a cultural association (and a garden) to rule the place. First to show our work, then the one from friends…’

Website: http://lesvoutes.org http://les-frigos.com

Les Voutes Artistic directors: Bruno Herlin and Pierre Wayser

Contract terms:

We do not receive any kind of funds or money !

We do not ask for money !

We do not want their money !

We do not have to say “thanks”!!

We just use some differents networks of international artists and share the expenses.’

Information provided by Pierre Wayser 59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivoli Aftersquat 59 Rivoli Aftersquat

59 Rivoli Aftersquat

Squat established: 1999

Owner: Bank of Lyon and then bought by the City of Paris

Expulsion by court of law: 2000

Regulated: 2001 (renovated and closed during 2006-2009)

Purpose: open studios to public everyday (except Monday) exibition space, artist studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 core members, around 30 artists working in building

Website: http://www.59rivoli.org

Contract terms: all artists are door greeters for 1 hour /week, each artist pays $160 for utility bills, building closes at 8pm

Information provided by: Swiss Morrocan La Générale en Manufacture, Sèvres

La Générale en Manufacture, Sèvres

Squat: established in 2005

Owner: National Education Ministry

Expulsion by court of law: 2006

Regulated: 2007 relocation to Sèvres

Purpose: exibition spaces, wood and metal workshops, photographic studios, temporary residencies

Association: 15 official members

Website: http://www.la-g.org

Art Residency directors: Sylvain Gelinotte and Jérôme Guigue

La Générale en Manufacture profile: Painters,VJs, scupltors, conceptual artists, performers, photographers, musicians, video artists, poets, drawers, young or older (mostly in the 30s), french and foreigner nationals (mostly are french speakers), somewhat famous and also perfectly unknown.

Contract terms: With the Regional Minister of Cultural Affairs (DRAC): ‘they pay the rent and we run the space for the benefit of our work and visiting artists. Using the space to run a company or renting it forbidden’

Association Rules: $70 per month membership fee to pay for power, internet connection and the insurance that covers everyone

Information provided by: Jérôme Guigue

Angie Eng, Paris, January 26, 2010