Previous Post Next Post

Monday, April 17th, 2017

Territories of Complexities

Guillaume Paturel

WhiteBox

March 29th – April 5th

Curated by Lara Pan

By Mark Bloch

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

“Territories of Complexities” was an appropriate name for this exhibition at WhiteBox. There was much more going on than met my eye that was not apparent from the start.

The nine large, seemingly squarish, seemingly abstract paintings unidentified by individual names that were exhibited on the walls of this large, squarish, indeed, white box-like space seemed earnest and straightforward. The show was a competent “suite” of works by a middle aged artist making fine art for just seven years after a couple of decades in the field of architecture.

But the more I looked, the more the works expanded within my field of vision. Then a chat with Guillaume Paturel, born in Marseille, France in 1970 and a graduate of L’École des Beaux Arts in Marseille with degrees in art and architecture enhanced my perception further. Finally, a tenth piece, a game changer, was added to the show between my initial visit and the opening, casting in concrete, well actually in plywood, the connection between art and architecture, the artist and his subject matter: surface and depth. It raised the stakes for me as a viewer as it raised the artist’s stratum in which to work from the second dimension into the third.

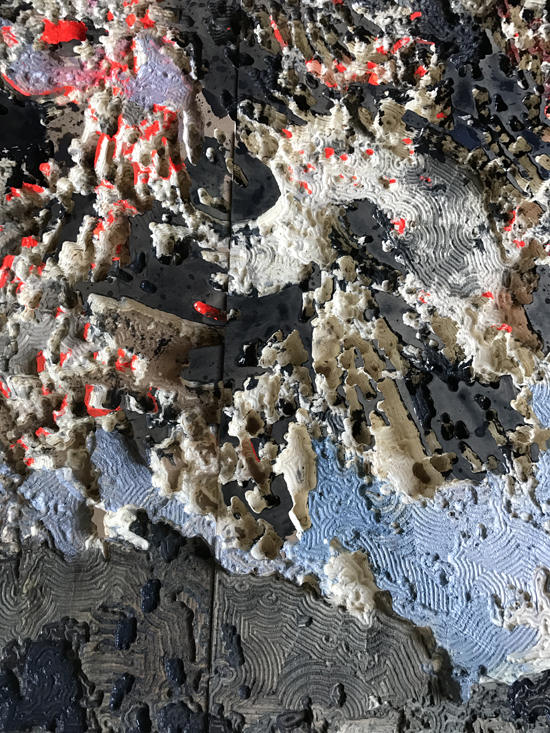

Though the artist Paturel and the curator Lara Pan, both alerted me that the new piece would be installed before the opening, I was not prepared for what I saw when I reentered the gallery. A striking “sculptural painting,” that Pan called “his first foray into the medium” now expertly occupied the center of the space, displayed close to, but not directly on, the floor, horizontally. This 4” thick solid wood slab had been ground, gouged and burrowed out by a robotic arm to create a topographical 3D object, fabricated directly from a painting now hanging behind it, behind the hand-painted peaks that seemed to be ascending ever so gently toward the ceiling like a hybrid between an accordion and an alien planetary landscape, and like the collaboration between man and machine that it really was. The texture was all machine-made. The inspiration and added color were by the artist.

That painting the sculpture “borrowed” from, and the other eight adjacent to it, were not square I now learned, merely by taking a second look and using my left brain, something not particularly engaged during my first visit. I could see that though similar to each other, these nine paintings, five or six feet across in either direction, were each unique in size, orientation and in the amount of power with which they projected energy into the space, toward the 3-D addition in the center of the room that, as a projection of one of the mostly “flat” works that surrounded it, seemed to bring them all into sharper focus.

Like the work seemingly hovering above the floor, each work on the walls contained silver, echoing the artist’s still thick head of hair, catching bits of light but not reflective. The nine pieces gently fought each other like extra terrestrial weather maps indicating chaotic, violent patterns traveling over coarse, scaly, abrasive, bumpy, scratchy planes aggressively, each supported by its own thick wooden structure and charting its own course. One was all silver. One was black with only silver wisps. Others were speckled and punctuated silver or shiny white or off white with a silvery sheen—with dotted tape textures and other colors emerging from below. Some had their supports painted dull black, others had other colors splattered on them and still others boasted only their raw wood grain as a foundation.

My first impression had not been correct when I first entered the space because their surfaces, seen from afar, appeared regular and monochromatic, polished, possibly smooth, ironed, slippery and fine—like so much of what one sees in galleries these days. But instead, these were what Paturel later described as his ideal: “dusty, ugly stuff.” They were, in fact, bumpy, sandpapery, scabby and cracked. When I asked the French man what he thought of American Ab Ex, he informed me that, to him, his art is not at all abstract. He sees his works as depictions of landscapes, geography, scenery, ground, and landforms. Any abstraction I detected was just the result of layers that courageously cover mysterious terrain underneath, which in turn cover thick skins of maps or guides, both of which alternatively familiar and confounding to the artist, I was assured.

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

Paturel still produces architectural renderings for some of the world’s top architects. Following the Beaux Arts, Paturel also attended Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris La Villette.

These paintings were, therefore, similar to topographical meanderings, but simultaneously important escape hatches from his work as an architect, needed imaginary extensions of the professional work he does for important sites like the new One World Trade Center tower and memorial or a sustainable city in Saudi Arabia. He is a gifted craftsman in both jobs, apparently. He recalls that before he was “tied to a computer” he had created, in a previous version of his profession, architectural renderings using handmade collage techniques with whatever materials were necessary to eek out his visions of practical structures not yet realized.

So perhaps missing that mode of handmade expression, he explains that these less practical works begin with the laying down of aluminum tape, building layouts of non-existant “cities.” His memory wanders through memories of previous projects for sites in The Bronx or Red Hook (where he now lives with his family) or in Dubai, where clients “asked for trees and grass and beautiful greenery” in the architectural renderings, but adds that once finished and he was on site, he witnessed “just landscapes of dirt and sand and policemen.”

And so he applies layers of paint. He scrapes to unearth underlying strata. On their exterior, these artworks show evidence of nicks and cuts and gouges, the surface forcefully indented creating external damage indented and intended and invented.

He told me that he does not favor the slick, cute, happy superficiality he sees in the work of many artist contemporaries. He prefers art like opera, showing passions or deep truths that elude us so I ask for his personal story, hitherto unavailable in my investigations. He looks at me long and hard and finally asks, “Do you really want to know?” I do. He tells me his work is not abstract, so I wonder, what is it? “My art fights death,” he tells me. “Creativity against decay, you know?” He finally volunteers that he is now an artist because he once told a lie then had to fight for his life to make it true.

His father called him to reveal he was fighting cancer one day out of the blue seven years ago in New York where he had moved after decades of them not speaking. From there they carefully rekindled their rocky relationship. Guillaume told him he was about to have a show, but it was a lie; there was no show. He was an architect, never an artist. But after he hung up the phone he went directly to the store and bought art supplies. He next arranged to have an exhibition and set to work.

Territories of Complexities. Photos courtesy of the artist 2017

As Guillaume watched his French father’s health drift in and out from afar, for the next seven months, he became an artist. He fought by creating his topographical worlds with memories of the bourgeois accents of his native Marseilles echoing in his head.

Guillaume reluctantly told me that at age seven physical abuse by his father was rationalized by telling him it was because of the “improper ” way he spoke for a boy from Marseilles. He thus descended from speech to stuttering and then to silence, as the whole topic of language became an enemy. Then at age 11 or 12, as suddenly as his speech had been beaten out of him, he fought his way back from 5 years of complete silence with sheer willpower, and learned to talk again, just as he became a self-taught fine artist only seven years ago.

Determined as he is, he does not like the headstrong way the builders of New York City clear empty lots for their architectural sites for new buildings. When they cart away the rubble, sweep away the refuse, remove the layers of detritus and dust and the urban patina, it breaks his heart. So perhaps he uses paintings to savor the currents of necessarily unpleasant emotion, unleashing and then covering them up again.

Under the tortured surface of silvers and blues punctuated by tiny reds, yellows or light greens, flows of metallic tape and pigment emerge like flows of electricity in his work, like the movement of electrically charged particles traveling in feathery shapes or colliding like shiny geysers or in matte areas hiding in shiny black.

Where my perception was once of cleverly concealed dispassionate, phlegmatic gestures, now that I’ve heard his story, there are patterns suggestive of vulnerably turbulent water or air in motion. Not smooth or polished surfaces but pockmarked, irregular geomorphology. Uneven, chapped, rugged and wrinkled membranes of trapped language.

I ask him again what artists he likes. He finally mentions Gerhard Richter and Anselm Kiefer. While Kiefer’s works are characterized by an unrepentant willingness to face his culture’s dark past, Guillaume confronts his own past, more similar to the media-shy Richter, an artist who does not want to talk about his work. Paturel’s art is speech that says something that part of him does not seem to want explained.

“My pieces are cities, territories, urban landscapes either deserted or under construction,” he says. “My city of choice is geometry and chaos, order and disorder, verticality and stratification.”

So let us return to the 3 dimensional horizontal piece in the middle of the room. He fabricated it with the help of some architectural colleagues from one of the paintings in the show that they turned into a digital photo and then into software that extrapolates information into 3D to create “tool paths” which tell a machine how to carve in 3 directions, at 5 different pivot points, ultimately directing a “CNC router” to carve away designated areas of the 4” thick slab of wood that stretches out as wide as the paintings on the wall do—again, 5 or 6 feet rectangles. Form burrowed away in concentric irregular rings around elevated surfaces look like tiny islands in vast oceans. To these surfaces and large areas of wood where the color in the original painting was converted to raised land masses, the artist added new layers of color, different from its topographical doppelganger, hanging on the wall behind it.

While the technology and the technicians did a spectacular job of recreating in three dimensions, the original turbulent layers of paint and texture, subtle and not-so-subtle, complete with tape interruptions and handmade scrapes and scratches, the painting that it was derived from takes its orders from a kind of plan that robotic arms and digital code can imitate and simulate and even expand in untold new dimensions, but never understand. Despite continued clean, tidy attempts to the contrary by the contemporaries of Guillaume Paturel, art is capable of unearthing suppressed language that whispers, sometimes desperately, sometimes mysteriously, but if we listen, complex territory is revealed.

Guillaume Paturel was born in Marseille, France in 1970. he earned degrees in art and architecture from L’école des Beaux Arts in Marseille and Ecole Nationale Supérieure d’Architecture de Paris la Villette. He has produced architectural renderings for some of the world’s top architects, including Sou Fujimoto, Didier Faustino, Mos Architects, Maurizio Pezo, and Sofia von Ellrichshausen. Other highlights include renderings for the new One World Trade Center Tower and Memorial and K.A.Care’s sustainable city in Saudi Arabia. Paturel is also an accomplished filmmaker whose works have been shown in film festivals in france and switzerland. Paturel has had solo exhibitions of his paintings in New York City at Fragmental Museum (2012), One Art Space (2013), and A+E Gallery (2015).https://guillaume-paturel.squarespace.com/

Mark Bloch (American, born 1956, www.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mark_Bloch) is recognized as being one of a handful of early converts from mail art to online communities.In 1989, Bloch began his experimental foray into the digital space when he founded Panscan, part of the Echo NYC text-based teleconferencing system, the first online art discussion group in New York City. Panscan lasted from 1990 to 1995. Following the death of Ray Johnson in 1995, Bloch left Echo and began a twenty-year research project on Communication art and Johnson, and wrote several texts on him that were among the earliest to appear online and elsewhere. Bloch and writer/editor Elizabeth Zuba brought together an exploration of Ray Johnson’s innovative interpretations of ‘the book’” at the Printed Matter New York Art Book Fair in 2014 at MoMA PS1. Bloch has since acted as a resourcefor a new generation of Johnson and Fluxus followers on fact-finding missions.

WhiteBox, located in NYC, is a non-profit art space that serves as a platform for contemporary artists to develop and showcase new site-specific work, and is a laboratory for unique commissions, exhibitions, special events, salon series, and arts education programs. WhiteBox was founded in 1998. http://whiteboxnyc.org/