Wednesday, April 23rd, 2008

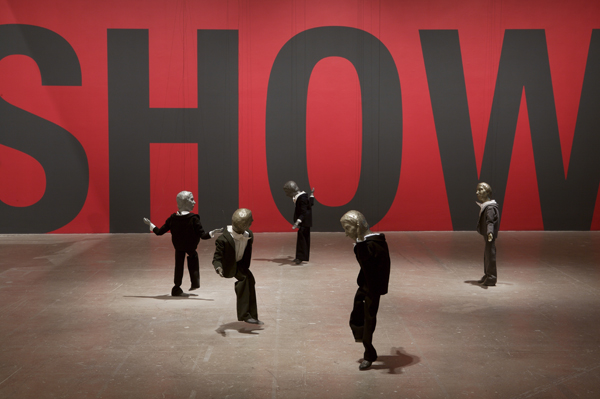

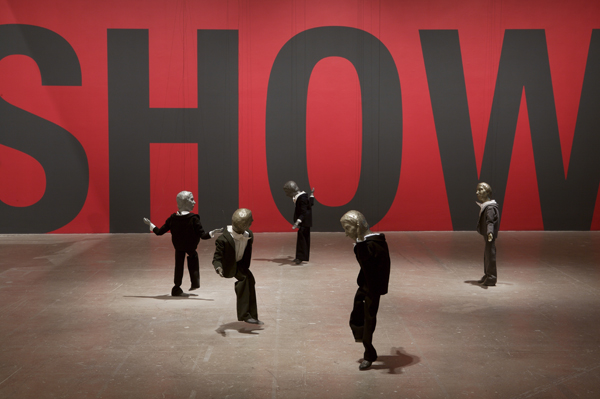

Dennis Oppenheim. Theme for a Major Hit, 1974. “The Puppet Show.” Installation view.

Institute of Contemporary Art. University of Pennsylvania. Photo: Aaron Igler

Puppets, Mortality, Humor and Suffering;

Three States, Three Venues Explored

AOA correspondent: Artist Eva Mantell

The Puppet Show, Institute for Contemporary Art in Philadelphia, Pa, from January 18 to March 30, 2008; traveling to the Santa Monica Museum of Art; the Contemporary Museum, Honolulu; The Contemporary Arts Museum, Houston; Frye Art Museum, Seattle.

Bianca Neve, Teatro del Carretto, LaMama E.T.C., NY, NY,

January 10 – 27, 2008; Teatro Araldo, Torino, Italy, April 18-19 2008

Argonautika, The Voyage of Jason and the Argonauts,

directed by Mary Zimmerman, McCarter Theatre, Princeton, NJ,

March 20 – April 6, 2008

Puppets look easy, child-like and direct. They are obviously about the body, about power, about imagination, about the self, about comedy and about mortality.

Any artist can drop in on this art form and give it a try. A puppet could be made from anything: your hands (Cindy Loehr gives us a video with talking fists which quickly reminds me of “The In-Laws” with Alan Arkin); your genitals (Guy Ben-Ner’s video gives a sometimes shy body part a star singing role); your whole body as you act like a puppet (Paul McCarthy, scary clown slopping paint around for us).

Puppets are about drawing and about sculpting too. Film, video, computer animation too. Robotics (Survival Research Laboratory lavishly blows up robots, which is certainly one approach). I think the thing vacuuming my neighbor’s home right now is a puppet. I’m pretty sure some of my children’s pets are puppets, that “live and die” by various digital reenactments of nurturing. And this month I had my first sighting of a Baby Think It Over Doll at, where else, the mall! A teenage girl, right out of an after-school special, is dutifully carrying her puppet baby, waiting for its electronic wail, her cue to turn a key in its back while it digitally records her mothering skills. Looking at her a little more closely: does she or doesn’t she? Is she also wearing a strap-on empathy belly?

http://www.enasco.com/product/SB43113G

Where, America, can you get a brain to strap on?

Memories can be strapped on or strung up: by Kiki Smith, Louise Bourgeois, or by Dennis Oppenheim with his mini-me’s. Playing with dolls can transport you to the realm of fear. Natalie Djurberg’s romps in a cardboard world are kinda sick, kinda cruel, kinda cool. Kara Walker’s shadows time-travel into a conflicted, messed-up American history. Her elegant lines are an ironic pleasure, a facade for the crude sadism that is the real story.

“The Puppet Show.” Installation view. Left to right: Anne Chu, Louise Bourgeois, Kiki Smith,

Annette Messager and Maurizio Cattelan in the background. Institute of Contemporary Art.

University of Pennsylvania. Photo: Aaron Igler

Take a break with someone else’s problems: Bruce Nauman’s dinner date gone yucky. Doug Skinner and Michael Smith’s potty mouths. The body and the world are about failure. Things regre

ss then fall apart. Chaos was a greek proto-god who got in at the ground floor. Ubu Roi, an early expression of things gone ape-shit almost gives a classical feeling to stuff going beserk.

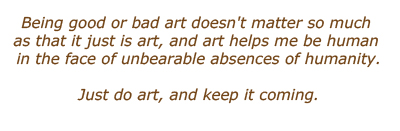

Ubu Roi and the Truth Commission, a play from South Africa, with William Kentridge on visuals, riffs on this little archaic psycho-policeman. The brutality of the regime, the document-shredding, the erasing of crimes, create, warp and envelop the testimony of the citizens’ suffering. This stuff is real and the art is just mediating the experience. Being good or bad art doesn’t matter so much as that it just is art, and art helps me be human in the face of unbearable absences of humanity.

Just do art, and keep it coming. Teatro del Carretto’s Bianca Neve (Snow White) at LaMaMa E.T.C. feels Medieval, distilled, sorrowful. A velvet lined box opens up in different ways to reveal shifts of scale, humor and suffering…from the miniature 7 dwarves to the terrifying full-scale actress portraying the witch/queen with an unmoving mask.

The mask that doesn’t move and the strings that don’t work are the stuff of nightmares. What we most need is agency in the world, connection, love, action and reaction. In the play Argonautika at McCarter Theatre in Princeton, early on, a marionette puppet of a baby wiggles its arms and legs making eager clicking sounds. I laugh at the repetitive, silly motions, but laugh too soon because now the king’s henchmen cut the strings, and leave it dead, noiseless, still on the stage.

Any fool knows that plaster, wood, screws and glue don’t add up to life, but puppet that I am, my heartstrings are pulled and here come the waterworks.

#permalink posted by Eva Mantell: 4/23/08 07:38:00 AMWednesday, April 2nd, 2008

Gema Alava: “Tell Me the Truth”at Messineo / Wyman

! Extended to May 2 !

March 20 – April 26, 2008

Messineo Art Projects and Wyman Contemporary

227 West 29th Street, 4th Floor (# 111)

New York, New York

by Ted Mooney

The truth is a hard apple, whether thrown or caught, as this young Spanish artist clearly knows. She tends, at her best, to think three or four moves ahead of her work’s viewers-not out of disdain for them or out of personal elusiveness, but simply to allow herself room to adjust her own thinking in relation to the effect her imagery has on her (rapidly growing) audience. One even gets the sense that these adjustments are what she’s most interested in. And that, if correct, is promising news indeed.

Alava’s most recent show, thoughtfully installed in Messineo / Wyman’s tiny 29th Street space, is breathtakingly elegant, deftly using the gallery’s space limitations to the works’ advantage. On exhibition are nine black-and-white silver gelatin digital photographs, printed on fiber paper and individually framed in white maple. Each work depicts, toward the left side of the print, a nail of indeterminate size-no scale is established in these works-protruding from a light gray, almost bluish ground that subsumes both foreground and background. Meanwhile, toward the right side of each print, emerging from a hole in this same placeless gray-blue void, are a few black threads, which seem to have ventured out along the ground to wrap themselves around the nail at midpoint or higher in what appears to be an attempt to uproot it from the security of its hole. A struggle, then-and so, inevitably, the appearance of a narrative. Each print shows the two elements-nail and thread-in a different state of dominance or submission relative to one another. At times the nail leans rigidly away from the threads, drawing them so taut they seem to fray almost to the breaking point. At others, the threads, exerting no less force, bend the nail savagely toward them, flexing it and nearly extracting it from its stubbornly held position. Occasionally, the two forces reach an equilibrium, though whether in exhaustion, momentary truce or even a hard-won peace, it’s hard to say.

At least on first encounter, it would be all but impossible for the viewer not to see in this struggle, which is presented to us as if on a completely featureless proscenium stage, the successive seasons in an emotional, probably romantic, human relationship. It could even, if the “time” interval between prints is imagined to be much shorter, be thought of as depicting various moments in a single act of lovemaking. The nail is undeniably phallic, the threads undeniably tactical in their approach and adaptive in their manner of struggle, almost certainly feminine. But no sooner has the viewer hit upon this fairly obvious thought-one even the most completely unreconstructed, frankly fanatical formalist would be hard-pressed to deny-than other, totally different questions begin to bubble up, one after another, in almost alarming profusion.

These questions begin with purely pragmatic speculations as to how these scenarios were physically created. The background suggests a space that is either infinite or non-existent, and, like someone who has just witnessed a magic trick, the viewer is seduced into trying to figure out how this effect was accomplished. Whether one arrives at a satisfactory answer or not, these speculations segue very quickly into the oddly threatening realization that there are absolutely no clues as to what the scale here might be. The force of the depicted struggle (as well as the size of the rather large, horizontally formatted prints) makes it hard not to succumb to the illusion that the stature of the protagonists-nail and thread-is equally epic. And yet when was the last time you saw a ten-foot nail? By now the sense that you are being manipulated is so strong that you begin to question everything. Where exactly can the physical tableaux that appear in the photographs be found? Why aren’t you being shown them, instead of what suddenly seems like photo-documentation of the real works, which are being denied you? Did the “true” art work somehow slip away between its physical embodiment and the trace of it preserved in the photograph? Or is the photo itself the art work?

And if these simple physical matters cannot be pinned down, then what about your earlier snap-judgment-strongly reinforced by the linear, apparently sequential installation of the photographs-that together they constitute a definite narrative, from image one to image nine (“The End,” as it were). Could the photos be resequenced so as to make a different “story”? Is the story you take from the photos really there, or is it a story you make from them because that’s the story you know: your story. Naturally, you then try looking at the prints in different orders to determine the possibilities. And so, by degrees, and quite unexpectedly, you find yourself stranded on a sparsely populated plain in the land of Beckett-or, more befittingly, given the artist’s Spanish background, that of Salvador Dali. (Note the Dali-esque shadows cast by the nail.) The seamlessness with which you have been transported from an almost cartoonishly amusing allegory of human relations to a place where some of the darkest fears and needs of the human heart are enacted-enacted and reenacted over and over again unto death-suggests that the artist’s intentions were, just possibly, not quite as innocent as you may have assumed. What you still have left to go on, however, is the title of the show: “Tell Me the Truth.”

To ask someone to tell you the truth-not a truth but the truth-is to instantly vaporize for good the very object of your request, the one that was so comfortably within your reach until you opened your mouth. Now the possibility of knowing the truth you asked for is forever denied you, because it died the moment you expressed your desire to hear it. This is something all unfaithful lovers know. And, however much we might wish it otherwise, when it comes to the truth, we are all of us unfaithful lovers.

Gema Alava’s work carries an uncanny power whose sourc

e lies precisely in how lightly she offers it. Often made from the humblest of materials, her art nevertheless gives off just the faintest trace of intense and prolonged concentration. Modest in scale, frequently fragile, it makes you think not of modesty or fragility but of resistance and struggle, life and death, the largest matters. Alava has a gift for effortless reversals that she does not hesitate to use in making her mortal point. And that point, more often than not, has to do with the universality of human suffering-cast by her, at times, in a Spanish key, for Spain’s suffering at the hands of history is well known. But the artist is under no illusion: such suffering is a condition of life, not of nationality.

Alava’s show remains open until April 26. See it now, before she becomes too well known for her work to be shown again in such intimate quarters.

copyright (c) 2008 by Ted Mooney

Artist: Gema Alava born Madrid, 1973. MFA San Francisco Art Institute, 2000. Her work has been shown at The Bronx Museum of the Arts, The Queens Museum of Art and, thanks to the generous collaboration of Cai Guo-Quiang, her latest art project took place at the Guggenheim Museum, New York, February 21st 2008.

#permalink posted by Ted Mooney: 4/02/08 01:05:00 PMTuesday, April 1st, 2008

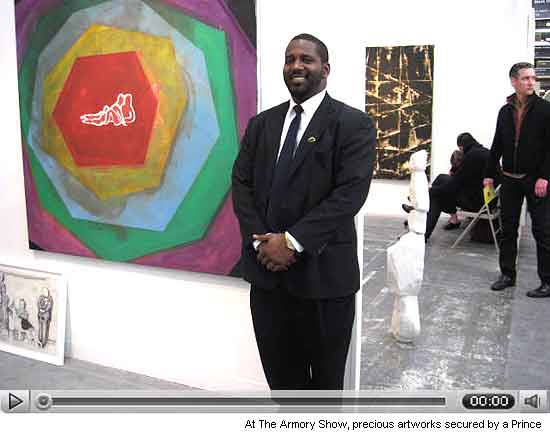

Rough and Ready at Pier 94The Armory Show

Jonathan Meese detail at Contemporary Fine Arts, Berlin

by artist Alison Knowles

For AOA

Convinced by a friend that I should see more art that is almost next door I ventured out with Bonnie Marranca of Performance Art Journal to the Armory show at 12th Avenue and 55th Street. Commenting that this is hardly next door on a cold March day she smilingly retorted. “There will be coffee. “Once inside there in my immediate sites was Leah Fried of the Lombard Fried gallery. She had the best show at the fair for my vote. His name is Michael Rakovitch, a third generation Iraqui American who started out by putting his sculptures in his fathers Import Export store on Atlantic Avenue. The work was so compelling one had to pick it up and look closely. About twenty small sculpture filled the table: dogs, shoes, lamps, perhaps all rejects from his father’s store I imagined. Each piece wrapped in a daily newspaper, impeccably glued and adhered smoothly so the Arabic or Turkish or English could be read. One had to guess the object that supported the newspaper accounts.

Leah was one of many friends that had shown up for this fair and she pointed the way to another series of works by Emily Jacir. These were clearly Fluxus like event accounts, suggesting to walk a certain street in Gaza and find one corner to observe. I decline to take the Gaza walk at this time, but the pieces were evocative of what this young Palestinian was going about to make art from her torn homeland. Then turning around there in my sites was artist/student from Cal Arts, Aviva Rahmani now in Maine. She is an artist doing a PHD as part of her “art practice”. Her field is ecology and she has repaired a huge pond water-site in Maine. Today she said “we have to think of knowledge particularly science as the material of art”. It is up to artists to start thinking and make their own archives available she said, as loose theoretical writing and reportage have made it necessary for artists themselves to communicate what they are about. I mentioned AOA to her: “It was great getting in with AOA. They said ‘we don’t care if you’re an artist, you have to be a writer to get in here.’ Fortunately, my Shoreline had my name attached as writer.”

Around another corner I found a work by Idris Khan titled “Hearing Voices”. A large spread of grayish notes based on a Schumann concerto had been transferred as a digital c-print onto aluminum, a glowing beautiful work. Finally with coffee in hand I could sit for a moment with Dominique de Menil, a strong and generous contributor to the work of John Cage for decades. She is the remarkable person who bought and island in the Caribbean and built a college there.

Julie Harrison informed me that Steve Clay at Granary of Granary books was not present but caring for the kids. She was sipping tea on a huge cushion.

“At The Armory Show an air of orderly professionalism pervades…”On the news just now I see that artis

ts in Brooklyn have rented a dumpster and are showing digital tapes inside for free entry. Because I am a member of Artists Organized Art I was able to bypass the line and get free entry by showing a work Shoreline on the Internet. It worked. They gave me a badge and let me through. The line was more than a half hour long and the fee $30. I disagree with this situation of large fees for museums and fairs. Clearly I better stick with those enterprising artists renting a dumpster in Brooklyn.

“At The Armory Show an air of orderly professionalism pervades…”On the news just now I see that artis

ts in Brooklyn have rented a dumpster and are showing digital tapes inside for free entry. Because I am a member of Artists Organized Art I was able to bypass the line and get free entry by showing a work Shoreline on the Internet. It worked. They gave me a badge and let me through. The line was more than a half hour long and the fee $30. I disagree with this situation of large fees for museums and fairs. Clearly I better stick with those enterprising artists renting a dumpster in Brooklyn.

photography: Erika Knerr

#permalink posted by Alison Knowles: 4/01/08 09:03:00 AMSunday, March 30th, 2008

Armory Show, NYC 2008The “Business As Usual” Slideshow

#permalink posted by Artist Organized Art: 3/30/08 06:53:00 PMMonday, March 10th, 2008

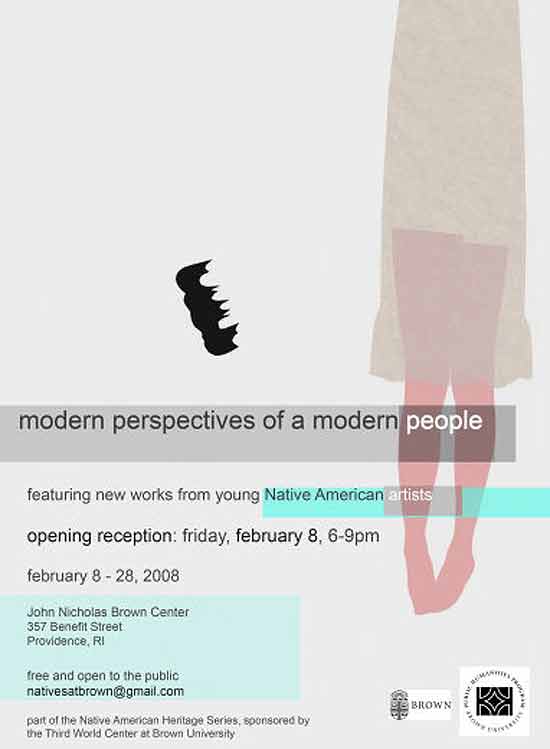

Modern Native American Artists

Artistic Expression: Modern Perspectives of a

Modern People

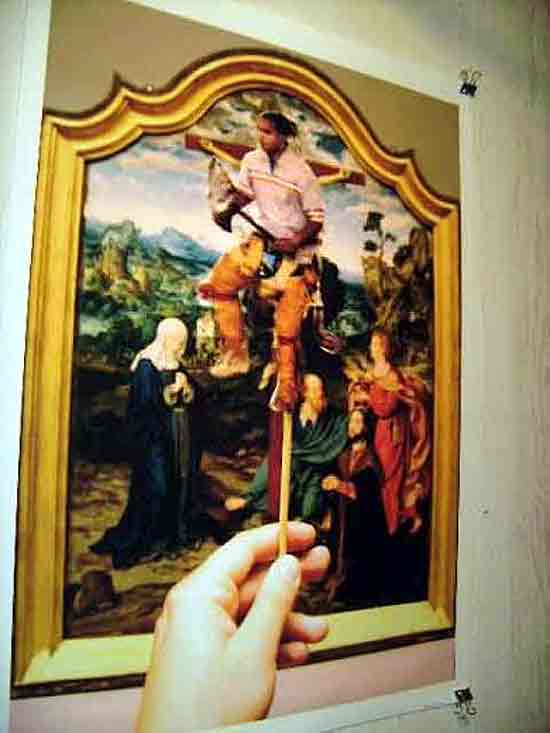

Dan Loudfoot, Everyone Wants To Be An Indian, participants, backdrop and photo document

Dan Loudfoot, Everyone Wants To Be An Indian, participants, backdrop and photo document

A Native American Heritage Series Event

February 8-28, 2008

John Nickolas Brown Center

Brown University, Providence RI

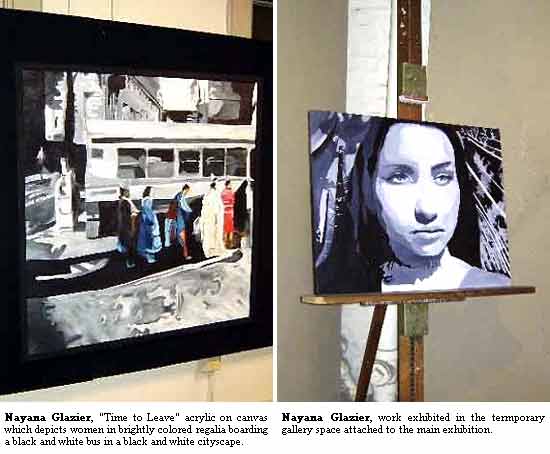

by participating artist, Nayana Glazier

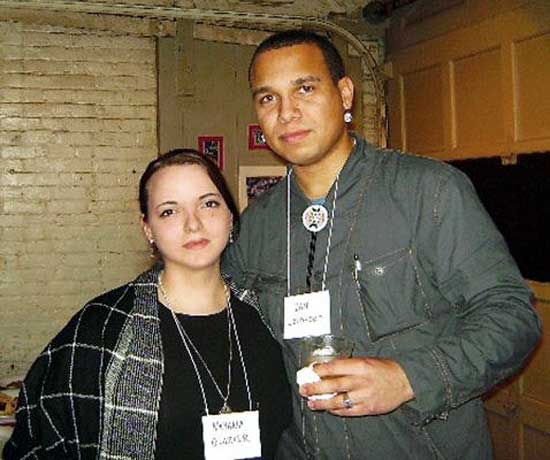

Friday February 8th was a day that I was apprehensive would ever come. I also never imagined it would happen with out my hands-on involvement. But a little over a month previous I received an email from Mikel Brown co-programmers of Native Americans at Brown (NAB) I was surprised. She explained to me their plans for an exhibition at the John Nicholas Brown Center at Brown University.

I experienced apprehension in the days leading up to the event. This came from the original reasons why Loudfoot, Echo-hawk and I had been planning the very same type of event previously. I wondered what the backgrounds were like for the other artists whom I was not familiar with. Did they have these same feelings? Did their work express the same ideas? Being of mixed blood would that affect their view of me or my work? These are all questions that I think all of the artists involved in this show probably thought in the days leading up to the reception.

Then it came, reception day, large white building with pillars and a stonewall with gate. We found our way in through the carriage house to what resembled a small parlor converted into the style of gallery you would see in most higher end New England colleges. Almost a cliché considering the subject matter of the exhibition. After hanging coats I found my way into the gallery to explore the works. Armed with my name tag and the knowledge that others were looking at me the same as I was looking at them. “There is another artist, I wonder what work they did, I wonder if they know I am one of the other artists, I wonder what they truthfully think of this exhibition.”

Upon entering the space I was immediately greeted by the over all composition of the room. The work was positioned clockwise around the chamber surrounding a large sculptural piece in the center. Pieces were numbered with an accompanying booklet filled with the names, tribal affiliation, and explanation of their work. I immediately grabbed my packet and made my way around the room. The space was filling up with other artists doing the same as the time approached for the general public to arrive.

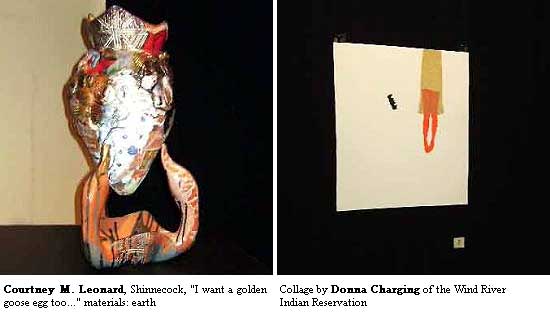

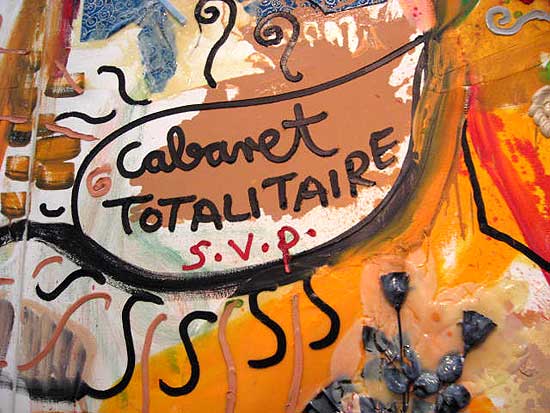

One, was a piece by Courtney M. Leonard, with the tribal affiliation of Shinnecock. Leonard is a grad student at RISD and presented a piece entitled “I want a golden goose egg too…” for which she listed the materials as “earth” Upon further exploration of the room I found she had a total of 3 pieces in the exhibit all of which had the same aesthetic and appeal to them. They resembled vessels and the first an egg with sculpted detailing and unique glazing. The thing that struck me most about them was the content of the imagery included on them. Stamps of strawberry shortcake and drawings of buildings adorn these traditional shapes as if to suggest the Americanization of her lifestyle and ideals. Almost caught between the two worlds of the traditional and modern. “Would this definition consider me as one (a traditional potter) if I admitted I began with play dough?” Leonard states in her explanation of her work. www.courtneymleonard.com Two as a cut origami paper and Rives BFK collage by Donna Charging of the Wind River Indian Reservation. This piece alluded to more but through her explanation I was unable to see the full truth behind it. The figure out of cut paper was suspended from the top right with what appeared to be hair, or a “scaling” falling away to the left. The legs on the figure seemed lifeless and dangling and I could not help but wonder what it was specifically about. I am unable to ask the artist this however and am still left wondering. www.donnacharging.worldecho.com

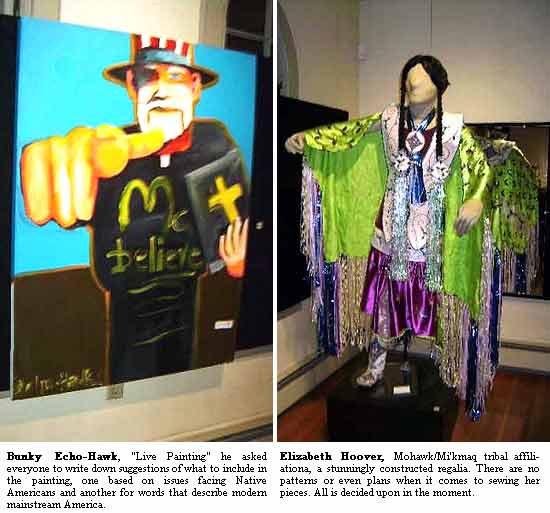

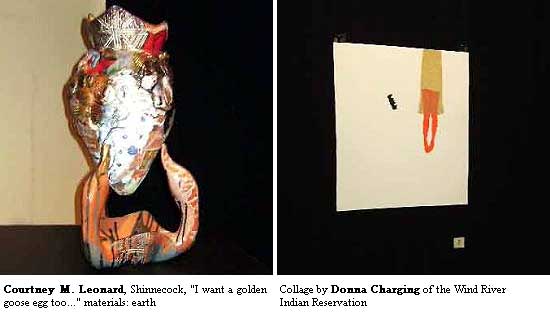

Three was a piece by Bunky Echo-Hawk, The piece featured had been produced as a “Live Painting” at Brown’s previous event in which he had set up to paint and did so by the suggestions of those in the room at the time. He asked everyone to write down suggestions of what to include in the painting, one based on issues facing Native Americans and another for words that describes modern mainstream America. People threw up ideas such as “domestic violence”, “Identity”, “mascots” and “fast food”, “Immigration” and “Britney Spears”. Ultimately it ended as a piece with a blue sky, almost annoyingly happy blue, with an “uncle Sam wants you” post to a man with a top hat and preachers uniform with blood trickling from the corners of his mouth and the words “Mc. Believe” across his chest. The piece as a whole is dynamic and impactful. The story of its creation just as much a part of the piece as the finished product itself. For a full article on this project visit this Brown-Daily-Herald-Link or www.bunkyechohawk.comFive was a stunningly constructed regalia by Elizabeth Hoover, Mohawk/Mi’kma

q tribal affiliation. This piece held onto its tradition wile incorporating the colors and ideas of the modern generations. I spoke with Ms. Hoover about her method and reasoning behind her work and found that she works much as a painter or other artist would. There are no patterns or even plans when it comes to sewing her pieces. All is decided upon in the moment, the works that result are as individual and intriguing as any other art form.

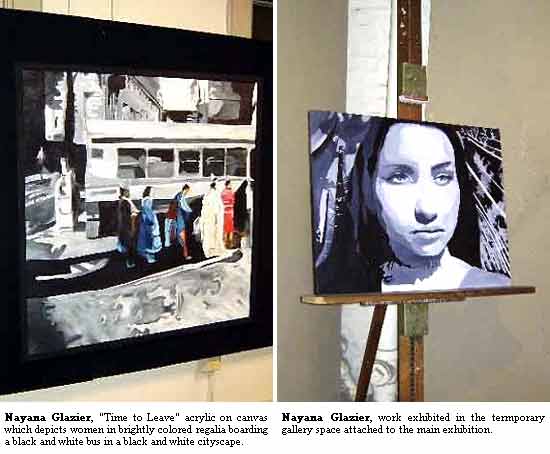

Six was my piece, I had submitted “Time to Leave” a large acrylic on canvas which depicts women in brightly colored regalia boarding a black and white bus in a black and white cityscape. This piece was meant to represent the idea of being in a modern city and feeling out of place, remembering what was once there in its place. www.picturetrail.com/nayanag

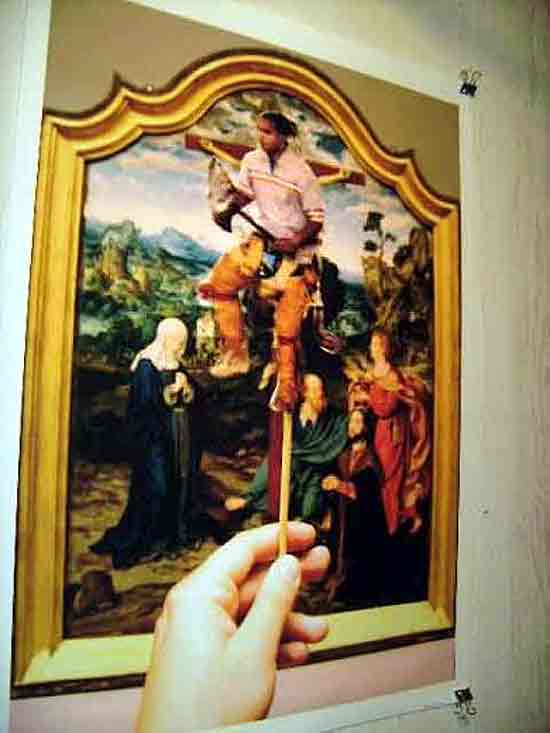

Dan Loudfoot, print enlargement with hand

Dan Loudfoot, print enlargement

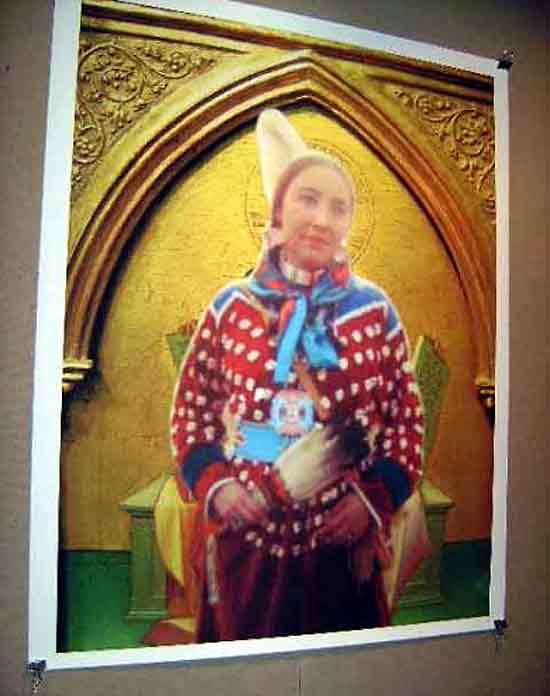

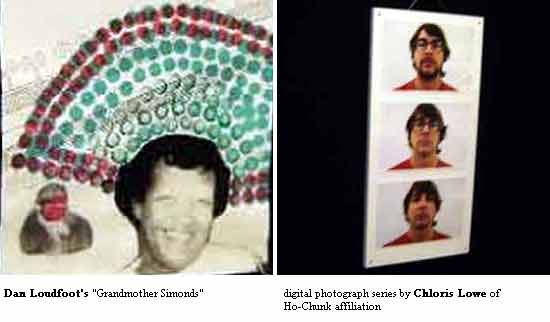

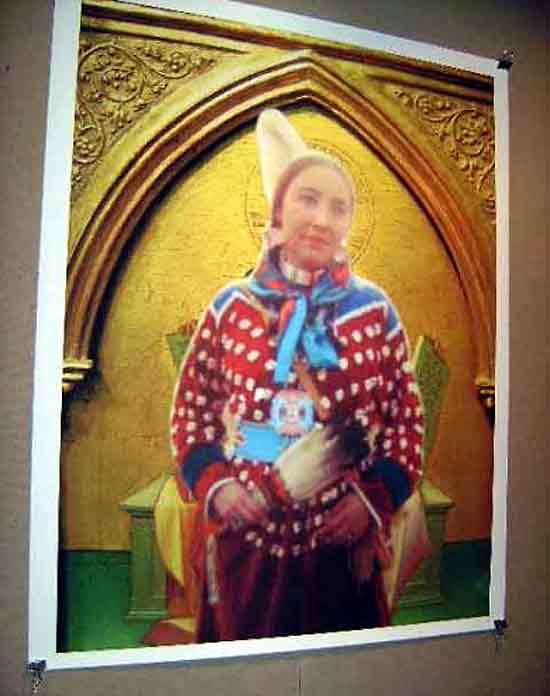

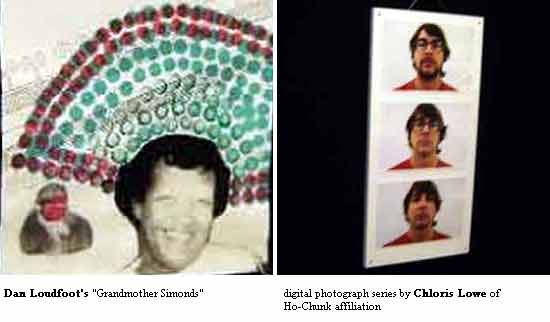

Seven was Dan Loudfoot’s “Grandmother Simonds”, he also had piece Thirteen “Everyone wants to be an Indian” and several pieces in the temporary room where the refreshments were held. Both pieces incorporate the use of bingo paint blotters to create traditional designs around a concept. In “Grandmother Simonds” he chose to put an image of his grandmother with that of a stereotypical Indian doll incorporating the bingo paint to form an almost mary-esque halo around his grandmothers head. “Everyone wants to be Indian” is an interactive piece in which visitors to the show sit in a chair positioning themselves to have their heads in the center of a circle of bingo paint with feathers at the top. These images will comprise a book when the exhibition is complete. www.danloudfoot.com

Four, a digital photograph series by Chloris Lowe of Ho-Chunk affiliation. This piece struck me because of its honesty and provocative ideas on identity related to being Native American. His piece spoke to me as a mixed blood native. Its title “searching for 1/4″ said it all for me. The series of three digital photographs, close ups on his face with small alterations such as glasses on or off reminded me of the experience of looking in the mirror searching for identity in what is easily seen. His physical appearance did not directly lead me to think he was of native ancestry and that is what made this piece the most interesting for me. There is always this feeling of non-acceptance for being or not being enough native and he tackled that issue in a ‘head on’ method. lowespaceartplace.blogspot.com  Winifred Bessie Jumbo, site specific placement of ritual objects

Winifred Bessie Jumbo, site specific placement of ritual objects

Eight and Nine are two dolls dressed in the traditional fashion by Winifred Bessie Jumbo of Navajo affiliation. Each element of the dolls outerwear means something about them and tells a story of where her life will go. These dolls are strangely generic in appearance as dolls themselves, it is what Jumbo does to them that make them unique and speak to the combining of ancient ideas and new ways. Her work speaks softly in its statement but has a deeper meaning that seems just within sight.

(picture unavailable)

Eleven were digital photographs by Jamie Spears of the RI Wampanoag who displayed images of her mother, cousin and cousin’s daughter at powwows. The thing that intrigued me about this work was the presence of such modern objects as head set microphones in otherwise traditional imagery.

Chloris Lowe, object, wood, steel, bronze and fabric

Chloris Lowe, object, wood, steel, bronze and fabric

Fourteen I almost did not see at all, which is strange considering it is the largest piece in the show and positioned in the very center of the room. I rounded the room and on my way out realized that there were two pieces remaining. The last I soon found just outside the doorway but this number fourteen I had almost not seen. But when my eye finally fixated on it the whole perception of the room changed and it became impossible to enter the room with out seeing it. The piece is by Chloris Lowe, the same person who did the photographs that I found so poignant. This sculpture incorporates wood, steel, bronze and fabric to make an intimidating but organic feeling structure resembling a box pulled open at the center to reveal the remaining elements. Lowe says this piece stems from ideas on the medicine bundle. The objects inside came from personal stories and experiences of Lowe’s.

(picture unavailable)

Fifteen is a digital image created in Adobe Photoshop by Donovan Pete of Navajo affiliation. Entitled “Withered” this piece incorporated elements of the modern and ideas on the traditional to form a graphically strong composition which makes us wonder about what might come next. Kind of a perfect ending for the whole event.

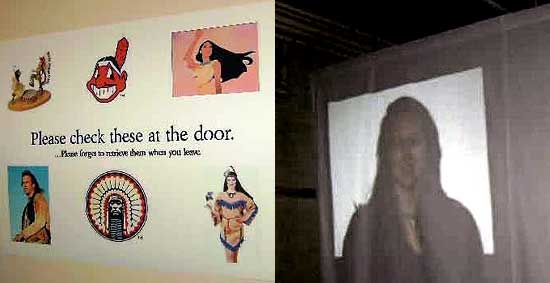

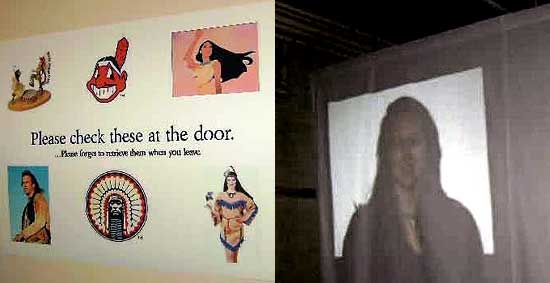

“Please check these at the door …Please forget to retrieve them when you leave”

“Please check these at the door …Please forget to retrieve them when you leave”On my way out I saw a sign at the door that I had missed on the way in asking us to leave our preconceived ideas on Native Americans at the door.

The turn out was fantastic for the space and the feeling in the room was an over all welcoming experience. Rather than the usual awkward interactions with other artists we found ourselves talking about our work and the ideas behind it. The overall feeling in the room was appreciation for the event-taking place. Each artist I spoke with expressed their experience of being surprised and excited that the topics handled in the show were being addressed and presented in such a public forum. Every person involved seemed to be genuinely excited and honored to be participating and have the opportunity to present these issues and ideas to the public.

Conversations on everything from art to history and pop culture were passed around as each of us found a small piece of the connectedness that so many of our works expressed the absence of.

Nayana Glazier and Dan Loudfoot

Nayana Glazier and Dan Loudfoot

Upon leaving to make the drive home I said goodbye to Dan Loudfoot, who I had only just met in person that night, we both expressed a desire to take this concept and the one we had begun before and have the show travel. We will now be looking for venues around the country where we can have this same sort of event.

The perspectives of the artist on art are rarely altered, except when faced with something that achieves what they themselves have tried to achieve but could not. Then I think the artist must look at things differently. This show did that for me.

– Nayana

#permalink posted by Nayana: 3/10/08 10:13:00 PMFriday, March 7th, 2008

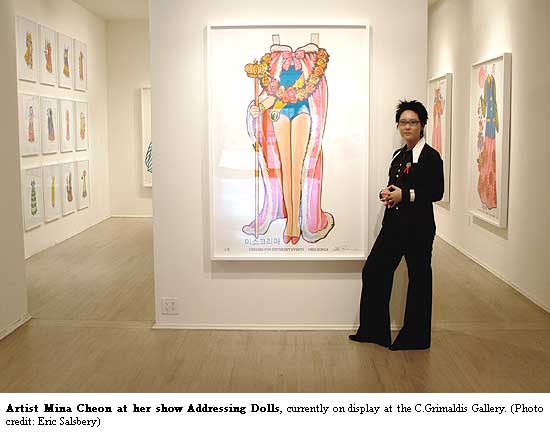

Embarrassment and Address

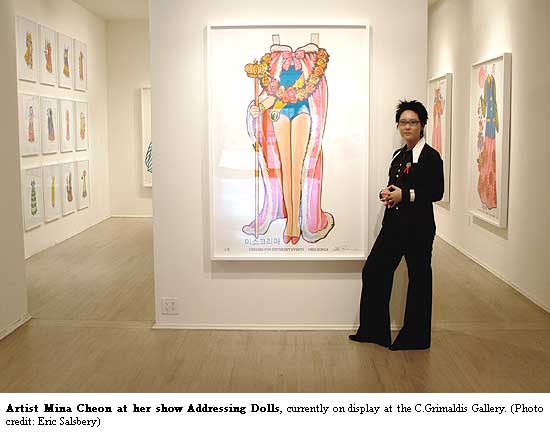

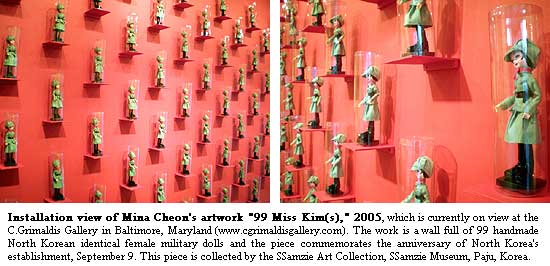

Mina Cheon’s Addressing Dolls at the C.Grimaldis Gallery

Baltimore, Maryland

by Brian Willems

Dollhouses first became popular in 17th century Western Europe. One of the most famous patrons of dollhouses at the time was Petronella Oortman of Amsterdam. If you go to the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam you can see some of her collection. Painted large upon the wall of the exhibition room, in English and Dutch, you learn that Oortman spent from 20,000 to 30,000 guilders at a time on the houses and their furniture, a price which could have purchased a real house on one of Amsterdam’s canals. This information is presented as shocking, and Oortman as wasteful. This is because dolls are not real, so they cannot appreciate or be comforted by their houses. Such devotion and extravagance lavished by the living on the non-living, however beautiful the outcome may be, is embarrassing. Embarrassing because care is given to that which is considered not to deserve it — the empty husks of dolls.

While embarrassment is usually thought of as a negative concept, in the artwork(s) of Mina Cheon’s exhibition Addressing Dolls it is a positive, strong and emancipating emotion. This is because embarrassment comes from being on unfamiliar ground. It comes from being subversively open to what is usually considered unimportant or impossible. Addressing Dolls foregrounds this unfamiliar ground by shining light on familiar tropes which have been manipulated within the thrust for Westernization in South Korean culture. In this sense the artwork functions in two ways: to focus our attention on the ways different kinds of dolls have been manipulated in Korean culture, and to highlight our own relationship to what is considered other than ourselves.

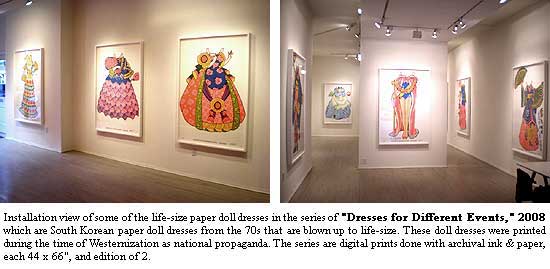

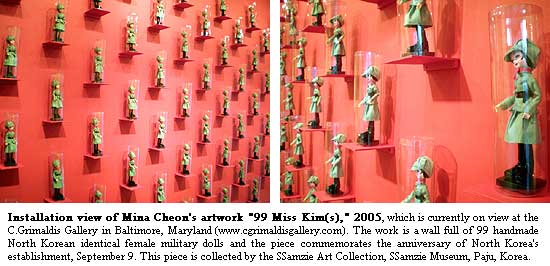

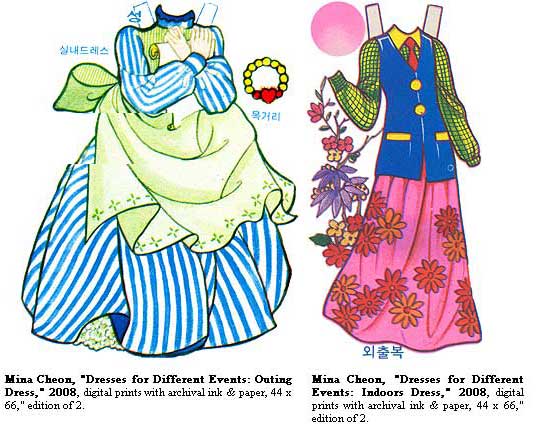

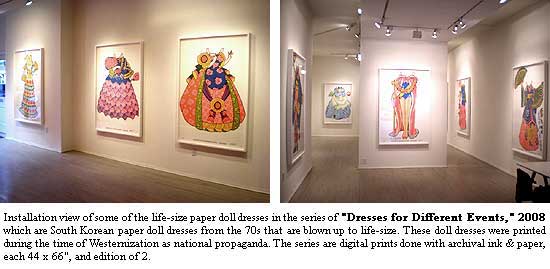

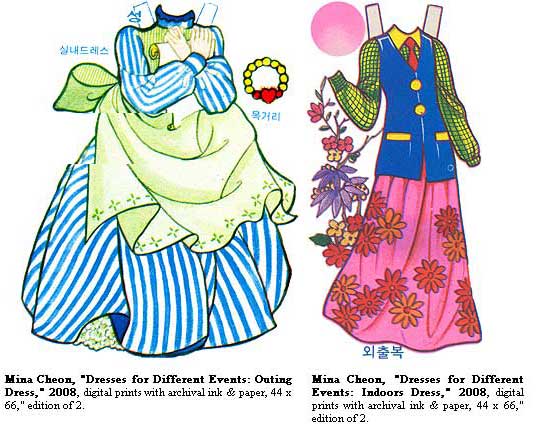

The focus of this exhibition is the trope of the doll. Its use is foregrounded firstly through repetition in 99 Miss Kim(s), which features 99 handmade female military dolls which were used to spread the propaganda of an oppressive North Korea, and secondly in the manipulation of scale in ten types of Dresses for Different Events, where frilly paper doll dresses are enlarged, becoming life-sized. These works call attention to the conflict present within Western and colonizing cultures in both Koreas and the way in which that has led to a conflicted relationship, and Cheon has worked on this cultural distortion by subverting the images and objects themselves. The repeated dolls of North Korean military femme bots and the blown-up Victorianized paper dresses of 70s South Korea do not let the viewer walk by, they do not let the viewer forget. Such a call-to-attention is embarrassing because it puts the viewer on unfamiliar ground by taking given and familiar tropes and putting them out there, exposed and open to scrutiny.

So where does that leave the viewer? Again, putting a positive spin on a term that is usually seen as negative, the viewer is left in a state of stupidity. In a sense, you can say that it is stupid to address dolls, to dress them, to cover them with wealth or ideas or to look towards dolls for answers, since they do not give anything back. However, it is in this state of a removal from what is usually considered intelligence that something new can come about. This removal can be considered a form of address because it is an openness to response, a turning towards and opening to. In this manner it is an address in the sense of location, of where you are dwelling. Such a thinking of the address of stupidity has been developed by philosopher Avital Ronell who argues that stupidity “tends to sever with the illusion of depth and the marked withdrawal, staying with the shallow imprint. Unreserved, stupidity exposes while intelligence hides.” This is what was meant above regarding embarrassment. What Addressing Dolls does is to expose through distortion. In this sense stupidity is that which is left when a positive answer is denied and instead what is held open is the moment of questioning, of the pencil poised above the answer sheet. As Ronell states, “Stupidity makes stronger claims for knowing and for the presencing of knowledge than rigorous intelligence would ever permit itself to make.” Cheon takes the manipulative and damaging tropes of the women as dolls in Korean culture and positivizes it by allowing an interaction with such tropes to become an action of embarrassing us out of ourselves, and allowing something else to become present, a knowledge more rigorous than intelligence would ever allow. Such a positivization is also a part of bringing the exhibition to the US from its showing in South Korea: by bringing Westernization back into the West, a sense of defamiliarization is lodged into the heart of the familiar.

So we become embarrassed addressing something that cannot respond, doubly embarrassed because assumed tropes of how the desire of South Korean female beauty is mimicked by Western standards and shaped by Korean expectations and imitation are exposed and such an exposure enacts a removal from intelligence, from what we know or accept, and thus we are put on unknown or at least unstable ground. The result of this exposure is that there is room kept open for the possible, for new thought. However, in order for such openness to exist, the other that is addressed must be allowed to remain in a position of strength. What is meant here is that it is precisely the other that has the strength to do work that we are not able to do, meaning, to bring us into a presencing of ourselves. In order for this presencing to take place, a relationship of what can be called embarrassment, stupidity or perhaps groundlessness needs to happen. Such a relationship to the other is denied these recent Korean artifacts for girls. However, when these manipulations are exposed and reworked, which is at the heart of Cheon’s work, a space for openness ha

ppens.

So in a sense in the 17th century Oortman could be said to have had the correct attitude after all. To lavish the non-responsive other with extravagance and surplus is a way of keeping its strength alive, of honoring its unknown. As Cheon wrote in a recent piece on the hand, “The dolls are interesting non-beings and a gift of my childhood when my hands were not big enough, strong enough, firm enough to hold scissors.” Perhaps it is only a risky, embarrassing and open relationship with a strong other that might allow us to have the ability to approach ourselves.

Brian Willems is an American assistant professor of literature at the University of Split, Croatia. His essays have appeared in or are forthcoming in artUS, A Tribute to Jean Baudrillard, Battlestar Galactica and Philosophy, From A to : Keywords in HTML and Writing and others. His poems and prose have appeared in Antioch Review, Poetry Salzburg Review, Hotel St George Press and others. He has a book forthcoming on Martin Heidegger and Gerard Manley Hopkins.

This text Embarrassment and Address is written for Addressing Dolls, Mina Cheon’s solo exhibition at the C.Grimaldis Gallery, Baltimore, Maryland, which is on display until March 29, 2008.

#permalink posted by Brian Willems: 3/07/08 11:58:00 AMMonday, March 3rd, 2008

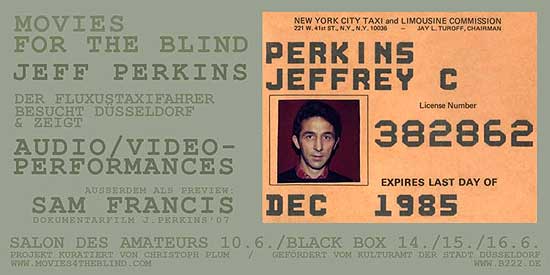

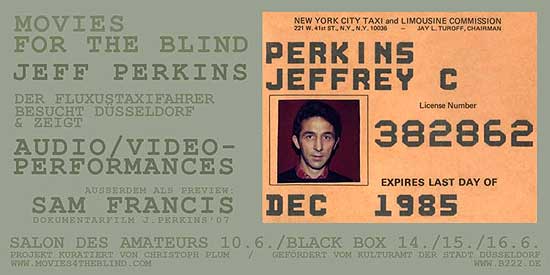

In Conversation With Jeffrey Perkins

an interview by Chiara Vecchiarelli

Jeffrey Perkins is a visual artist and filmmaker who recently resurfaced at The Emily Harvey Foundation in Brain Damage on Broadway, an evening of hypnosis, experimentation and psychedelia organized by artist Taketo Shimada of Messages. Years ago Jeff co-founded Single Wing Turquoise Bird, who provided light shows to Velvet Underground, Grateful Dead and Dr. John to name a few and on October 25’ 07, through Shimada’s initiative, resurrected his first light show in thirty years to the sounds of Shimada’s own collaborative project Messages. But there is far more to know about Perkins, a decades long associate of Yoko Ono, John Lennon, George Maciunas and Nam June Paik among many others. While serving in the U.S. Air Force stationed in Tokyo in the early 1960’s, he met Yoko Ono and her husband Anthony Cox. Through them he was exposed to the works of Cage, Duchamp, LaMonte Young and others and began participating in events, performances and concerts. Jeff currently exhibits at the Emily Harvey Gallery and is now finishing up his new film ‘The Painter Sam Francis’.

IN CONVERSATION WITH JEFFREY PERKINS

ART AND USE, WITHOUT INSTRUCTIONS

The following interview took place on a day in December 2007 in Jeffrey Perkins’ loft, in New York. We had just seen his last documentary film The Painter Sam Francis. The catalogue of the Venice Biennial historic exhibition Ubi Fluxus Ibi Motus, of which he took part, was among his books, together with a program of the experimental Cinematheque Theater 16 that he directed in Hollywood, and his personal copy of the Fluxfax Portfolio. On the floor, two suitcases fostering hours of interviews with passengers Perkins used to record in his cab, following Nam June Paik’s advice.

Jeffrey Perkins is the author of original performances, the discreet story teller of Sam Francis’ work, the friendly camera operator of Yoko Ono’s Film #4. Above all he is the witness of the fact that art is the place where the singularity of one’s own practice coexists with the sharing of ideas. Concepts that animate his practice are the source of his artistic and personal charm and one of the most interesting issues I really would like to deal with, in thinking and organizing art.

…

Chiara Vecchiarelli (CV): I like the idea that the material was nothing but the medium for your practice ….

Jeffrey Perkins (JP): … Fourier felt that the direct channel from the producer to the consumer was the most ideal thing, because when the broker gets involved the broker doubles the price … A talisman! Exactly, a talisman! This Fluxus publication bears the title: “How communists must give revolutionary leadership in culture.” I chose my rent. I rented out for very cheap, no profit …

CV: What is interesting is that Fluxus proposed an economic alternative system and that you are still proposing it in your everyday practice, in your small economic world…

JP: … I’m also thinking of the artist George Brecht’s ideas … Flynt used to say to me … “this place is more important than any art museum in New York City.”

CV: Joseph Beuys associated himself with Fluxus in the beginning … Can we speak of a social sculpture in your work, or rather of a social sculpture that presents itself in the collateral effects of your work …

JP: I read an interview with Beuys … he probably became aware of the Fluxus avant guard art, where art could really expand, which happened to me when I met Yoko Ono in Tokyo and I read John Cage’s book on silence. We saw the work in Anthology, and suddenly I was exposed to a new universe, a new doorway to what I thought art was … When I first saw Beuys’ work, his pictures and magazines, I immediately understood what he was doing … Why is there a room in the Pompidou with a piano wrapped in felt … I guess this is what the French situationist, Guy Debord, wrote about. I think I’m a situational artist …

Taketo Shimada is an artist organizer, visual artist and musician from Tokyo. He has lived and worked in NYC since the mid 80s. He has worked with a variety of figures such as Henry Flynt, Alison Knowles and Rammellzee to name a few.

Tres Warren is an artist and musician living and working in New York City. He’s involved in various music collaborations including Messages and has performed as part of Damo Suzuki’s Network, in addition to recording and touring internationally with his band Psychic Ills.

Messages – a duo comprising Tres Warren of Psychic Ills and visual artist Taketo Shimada.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1wX4sLROkLY]

Messages at Roulette

The Emily Harvey Foundation is a private foundation registered in the State of New York.

#permalink posted by Chiara Vecchiarelli: 3/03/08 02:58:00 PM