Entries Tagged 'Uncategorized' ↓

Monday, October 4th, 2010

Nuit Blanche, Toronto, 2010

Reunion 2010 @ Reyerson Theatre

A prepared chessboard positioned under a film and rigged with

electronic sensors to project play-by-play live interaction on the screen itself.

photo: Jessica Higgins

Jessica Higgins

Alison Knowles

“Nuit Blanche was originally conceived in Paris, France in 2002, in an attempt to bring contemporary art to the masses in public spaces. Now universally translated as ‘Sleepless Night’, Nuit Blanche brings more than a million people to the streets of Paris every year. In 2005, Paris organizers contacted the City of Toronto’s Special Events office with an invitation to join the ranks of approximately six other European cities producing similar all-night events. The international success of Nuit Blanche continues to build each year and has expanded its reach beyond Paris to Brussels, Rome, Bucharest, Riga, Madrid, La Valette, Portugal, Tokyo, Montreal and Leeds – each offering its own version of the all-night art extravaganza.”

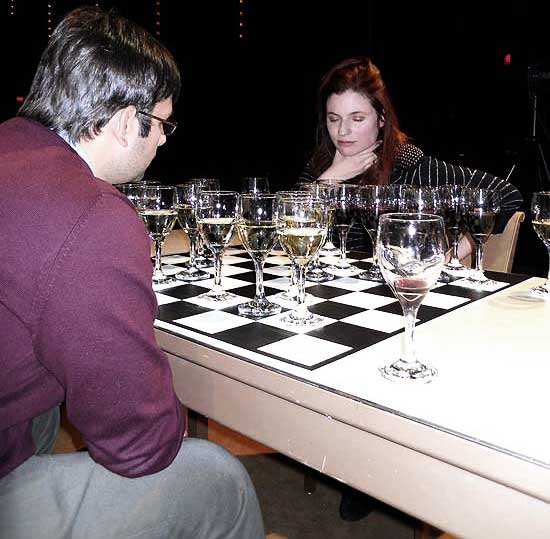

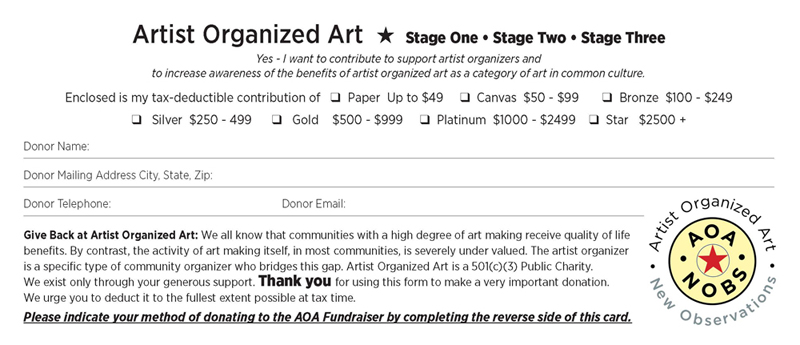

Takako Saito’s chess game.

32 glasses of different wines each representing a chess piece.

photo: Jessica Higgins

The organizers of our all-nighter in Zone B at the Ryerson Theatre were very good to us, arranging limousines, planes, hotels, tours and gala evenings. Our all night event, Reunion 2010, joined in the 5th Annual, which, this year, took place in Toronto on October 2nd, from 6:57 PM until sunrise. Reunion was one of many events that took place in different zones of Toronto, but this one had its unique twist. “Reunion with Marcel Duchamp, John Cage and Teeny Duchamp had previously been done at Toronto’s Ryerson Theatre, Gerrard St. East, in 1968. This year was to be a site-specific comment on the original for the Nuit Blanche 2010 nocturnal marathon.

David Behrman and Gordon Mumma, wove flute, violin and electronic sounds

to accompany every move of a chess game.

photo: Jessica Higgins

Toronto was the first North American city to fully replicate the Paris model, and has inspired similar celebrations throughout North America, including San Francisco, New York, Miami and Chicago.

However, using adaptation rather than replication, Reunion 2010, the all night event at the Ryerson Theatre, re-framed the classic film of Duchamp and Cage playing chess, with real time encounters viewed on a huge screen by the Ryerson Theatre audience. Prepared chessboards were positioned under the film and rigged with electronic sensors to project play-by-play live interaction on the screen itself. The art historical genre was bent into participation cinema, blending the paradigms high-art meets turn-based-strategy with paradigms normally associated with pop, such as from The Rocky Horror Picture Show, to the utilitarian, like extreme fat burning videos, audience participations included actions, invectives and frequent prize fight chants such as “take it with the queen!”

Takako Saito and Larry List sit on an on stage couch watching

the participation cinema of interactive electronic chess.

photo: Jessica Higgins

It was unusual to structure a return to experimental art in the context of a 12-hour city-wide event with a mandate to make contemporary art accessible to large audiences. While the festival inspires dialogue and engages the public to examine its significance and impact on public space, Reunion 2010 required an installed base of connoisseurs, and, with little surprise, Toronto did not let us down. Along a certain curatorial tradition, Nuit Blanche is both a “high art” event and a free populous event that encourages celebration and community engagement. Though usually in forms more easily assimilated by today’s metro-tourist.

By contrast to the “free concert of contemporary music” two long-standing composers who had worked with John Cage, namely David Behrman and Gordon Mumma, wove flute, violin and electronic sounds to accompany every move of a chess game. Without the game dynamics there were few contours to shape the event. However, even this became predictable, therefore chess masters, one from the U.S. and the other from Canada, paused in their game for the passionate intervention of Malcolm Goldstein sounding his iconoclastic violin (nearly in half) for more than an hour.

William Anastasia and Dove Bradshaw, Reunion 2010 at the Ryerson Theatre re-framed the

classic film of Marcel Duchamp and John Cage playing chess,

with real time encounters viewed on a huge screen.

photo: Jessica Higgins

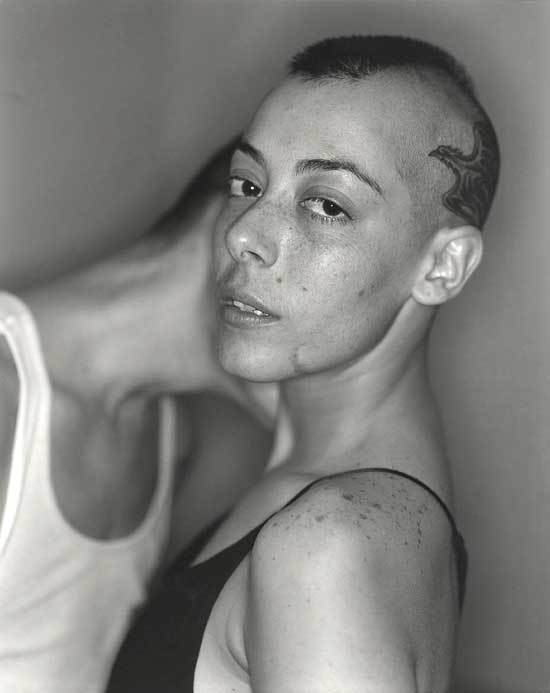

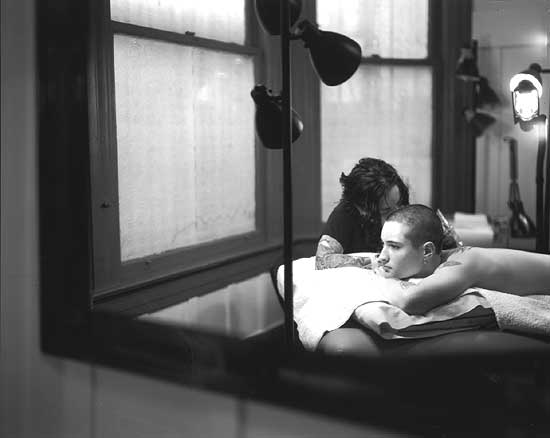

Other intervening performances included ours, of “Loose Pages”. This performance features different types of handmade paper positioned on the body for sounding by each motion. The garment by Alison Knowles, made entirely out of paper, is in seven parts corresponding to leaves “torn from the pages of…” going from hat to slippers to leg covers and wings as arms. Artist, Jessica Higgins, is dressed by Fluxus Founder Alison Knowles in the paper garment and becomes a living sculpture, dancing slowly on a low platform under a floodlight. She is sounded and guided by Alison Knowles. Because of the real relationship between Mother and Daughter which exists when we two artists meet to perform the work, our presence touches on very primary aspects of cultural adaptation, such as dressing rituals between mothers and daughters in ancient and contemporary societies.

Takako Saito brings art into everday life using a wearable chess set.

photo: Jessica Higgins

Toronto’s Scotiabank Nuit Blanche has wholeheartedly embraced principals of art into everyday life, though the reverse was still at its best in Takako Saito’s process work as chess game. Her approach was to cross euro-centric categories of sophistication by activating 32 glasses of different wines each representing a chess piece. This work was performed by high end pro-chess masters, who found temptation a new opponent as the game wore on. Alternatively, William Anastasi and Dove Bradshaw’s game design used hors d’ouevres as chess pieces. The edible artifacts were consumed as the game proceeded.

Jessica Higgins performing Loose Pages with Alison Knowles

photo: Jessica Higgins

The ambitious, if somewhat iconoclastic, red-eye art-shift was successfully curated by Sarah Robayo Sheridan who arranged the grand proscenium stage into a gracious interplay of events over a long night. As energy flowed from infinite supply, David Behrman wrapped things up with a long Cage performance that began at 5:30 am, leaving all of us sleepless.

Jessica Higgins/Alison Knowles

Toronto’s Scotiabank Nuit Blanche has wholeheartedly embraced principals of art into everyday life, though the reverse was still at its best in Takako Saito’s process

#permalink posted by Artist Organized Art: 10/04/10 10:18:51 PMFriday, September 24th, 2010

In And Out The Window

Fluxus-Plus Museum, Potsdam 2010

Alison Knowles, In And Out The Window, Fluxus-Plus Museum, Potsdam, 2010

Alison Knowles

From: “Alison Knowles”

To: “Joshua Selman”

Subject: Potsdam to Lodz

Date: Fri, 24 Sep 2010 22:05:34 -0400

Even though these events took place back to back in June and in another country Artist Organized Art was in full flower. AOA was present first of all in Potsdam where I had a two person exhibit with my friend Ann Noel who was for years partner to Emmett Williams. Our show was titled ‘In And Out The Window.’ I provided the windows, 4X8 foot open frames to walk through that had hangings of found objects on strings to be examined and sounded as one passed through in an leparello or accordion style installation that diagonaled through the huge factory space under vaulted ceiling with skylights.

Alison Knowles “Illiad Oddities” found object panel with Greek text concerning voyages,

cyanotype and Homer’s text by hand, 135×280 cm. In And Out The Window, Potsdam 2010

Ann’s work is straightforward art, framed and hanging on the wall. You could just stand there and admire beautifully organized diary panels in full color, really large. The painting consisted of what people were saying to each other on a given day. Each speaker had a different color strip with letters in english in black. It was intermedia and very fine, to read a painting. A key listed the speakers and the works covered three walls. She also did a performance cooking up something totally inedible but fun to see and smell. Some ate it but the museum (the Fluxus+ Museum in Potsdam) was very crowded at the opening. The director Heinrich Liman seemed very pleased with the transformation of his cement manufacturing company factories into one huge museum on the outskirts of Berlin. It had been his dream that he would do this when he retired. One could sit outside the cafeteria of the museum and feel fresh spring air over cold wine. I wanted to see more of him.

Alison Knowles, In And Out The Window exhibition detail,

diagonal walkthrough environment with xerox and film on laid paper,

Fluxus-Plus Museum, Potsdam 2010

Ann and I trained over to Lodz in Poland to be part of the Lodz Biennale. This was a terrific event titled ‘The Mad Hatters Tea Party’ which she curated with Ryszard Wasko. I have known him for some years as we all have and knew this would be quite a cup of tea! Fluxus regulars had gathered, including from Europe, Eric Andersen and Ben Patterson. At each serving someone stood up from the table of twelve and did something. There were ten surrounding tables in the huge church hall clustered around our main dining table. I remember Geoff Hendricks changed the color of potatoes to green, Eric passed out quizzical cards, Ben Patterson did some strange actions with ice cream. When my turn came I pulled a bag of red lentils from my bag and threw them in the air aiming at the adjacent tables. We drank wine, enjoyed Ryszard and the show he had up and wished again, I wished I could have seen more of him.

Heinrich Liman, Director in his Fluxus+ t-shirt,

with Fluxus Experience Author, Hannah Higgins and her daughter Nathalie,

In And Out The Window, Potsdam, 2010

Heinrich Liman and Ryszard Wasko survive because they are great people who have made themselves happy by throwing their identity with Fluxus which is today as always a dedicated avant garde if somewhat diminished in numbers.

Please sign up for The Identical Lunch at the MoMA Thursday and Friday of January. That’s my tuna sandwich made to order in the cafeteria at noon. I’ll be there to greet you and take you to the show around the corner one flight up. There will be a formal invite on the internet airing (I like streaming) on Jan. 3 2011.

Alison

–

Ausstellung IN AND OUT THE WINDOW

Alison Knowles, Ann Noël

Ausstellung vom 25.06.- 29.08.2010

Performances Vernissage Freitag, 25. Juni 2010, 19.00 Uhr

IN AND OUT THE WINDOW, der Titel der Ausstellung erinnert an ein Kinderlied, einen Reigentanz. Die Tanzenden reichen sich die Hände, öffnen mit den Armen “Fenster”, nehmen den Nächsten mit. Das Lied endet mit “And see what you can see!” – genau diese Forderung stellt sich in der Ausstellung.

Die amerikanische Künstlerin Alison Knowles zählt zu den Gründungsmitgliedern der Fluxus-Bewegung und erarbeitete zahlreiche Fluxus-Performances wie “The Identical Lunch” (1969) oder “Make a Salad” (1962). Andere ihrer Arbeiten gehören zur Klangkunst oder wurden als Hörspiele konzipiert. In ihrem Werk sucht Alison Knowles die Verbindung zur Natur und deren Wandel. In der jetzigen Ausstellung werden begehbare Rahmen ihre Arbeiten tragen und den Besucher zum Durchschreiten einladen. In der Nachbarschaft gefundene Objekte hängen an Schnüren im Raum. Der ursprüngliche Sinn bleibt wie ein Traum in der Erinnerung. Drei Meter Tuch spannt sich über eine Wand und zeigt Kuriositäten, ganz im Sinne von Fluxus, als das Leben zur Kunst erklärt wurde.

Ann Noël ist eine vielseitige bildende Künstlerin, die sich mehrmals an Performances und Ausstellungen mit Fluxus-Künstlern beteiligt hat. Sie wird in Berlin von der Emerson Galerie und in Zürich von der Galerie & Edition Marlene Frei vertreten. Für die jetzige Ausstellung lässt sie farbige Foto-Collagen mit ausgewählten Papierfundstücken und Texten (Kinderreimen) lebendige Geschichten erzählen. Die Künstlerin präsentiert neue Mix-Media-Arbeiten und farblich übermalte Namenstafeln aus den Texten ihrer Tagebücher 1989-2001 unter dem Titel “CONFLUX II”. Während der Performance am Freitag, 25. Juni 2010 werden 12 kleine Leinwände als “FLUXUS HORS_D´OEUVRES D´ART” fertig gestellt.

In mehr als 40 Jahren kreuzten und trafen sich die Wege der beiden Künstlerinnen immer wieder. Nun zeigen Sie in ihrer gemeinsamen Ausstellung, wie aus künstlerisch verarbeiteten Fundstücken Collagen und Assemblagen werden. Zahlreiche Werke der Beiden sind Teil der Sammlung des museum FLUXUS+ in Potsdam.

Zur Ausstellungseröffnung am Freitag, dem 25.06. um 19.00 Uhr sind die Künstlerinnen anwesend und performen “Fluxus hors d’oeuvres” und “Fluxus with tools”. Für diese Eröffnungsveranstaltung bittet das Museum um einen Kostenbeitrag von 10,- / ermäßigt 6,- Euro. Ein Besuch der Dauerausstellung bis 22.00 Uhr ist in diesem Eintritt enthalten.

Das Museum enthüllt um 21.00 Uhr anlässlich dieser Vernissage die “Hommage à Emmett Williams”; eine beleuchtete Außenwandinstallation. Die “Little Men” vom Fluxus-Künstler Emmett Williams werden von nun an auf der Havelseite des Museums farbenfroh die Besucher der Schiffbauergasse grüßen und in das Museum bitten.

Weitere Informationen unter www.fluxus-plus.de

Wenn Sie keine Newsletter-Informationen des museum FLUXUS+ mehr haben möchten, senden Sie uns bitte ein “abmelden” an info@fluxus-plus.de. Danke

museum FLUXUS+

Schiffbauergasse 4f, 14467 Potsdam

Fon: (0331) 60 10 89 – 22

Fax: (0331) 60 10 89 – 10

info@fluxus-plus.de / www.fluxus-plus.de

#permalink posted by Artist Organized Art: 9/24/10 11:00:14 PMTuesday, September 14th, 2010

On art;

or the law, blindness, and possible gestures of virginity

Kenny Png, Writer, Director, Soundscape & Visual Designer of ‘The Boxes’

by Artist Jeremy Fernando

The spectre that haunts every work of art, every attempt at a work of art, is that of originality; of whether what one is attempting to do has already been attempted, or even worse, accomplished. After all, no one wants to be deemed a mere reproducer.

Here, one can hear a trace of an obsession with beginnings, and the fantasy of the original; along with a longing for the aura that surrounds the first, the beginning, and the power it brings with it—of credibility, of authority, of being the source. Perhaps this is why correction fluid has become indispensable in our stationary drawers: as if by writing over a word, a line, a smudge, putting a layer over it, we can cover it up, erase it completely; as if banishing it from sight will equate to banishing its memory, banishing it from memory. The underlying logic is that in order for anything to be important, one has to be the first to do it; more importantly, traces of all others have to be wiped away. In other words, one has to produce; not reproduce.

In some way, this is a hangover of the Enlightenment; specifically with regards to the belief in transcendental Truth(s) and origins. It is this hang-up over the power that comes with being the first—the author—that lends itself to the societal obsession with virginity, with virgins; a desire to be a virginal experience, the virginal experience. Along with this fixation of being a primordial experience comes the notion of absolute knowledge; as if being the first means a mastery of the situation.

At the tail end of March 2009, we heard rumbles of this in the controversy surrounding the Wild Rice—a highly-regarded Singaporean theatre company—production of Oscar Wilde’s The Importance of Being Earnest. The show was given “an advisory rating of ‘16 years and above’ to avoid confusion ‘about its content and underlying messages’ among younger audiences and those who are unfamiliar with the play” by the Media Development Authority of Singapore,1 ostensibly for having an all-male cast. Most people presumed that the MDA rating was due to the foregrounding of gender; which either unveiled the performativity of gender, or even highlighted the alleged homosexual undertones of Wilde’s work. Of course, they completely missed the point. What was at stake was far higher: the primacy of the author. By having an all-male cast, Wild Rice was staking a claim for reading—where the text comes into being in and through its reading.

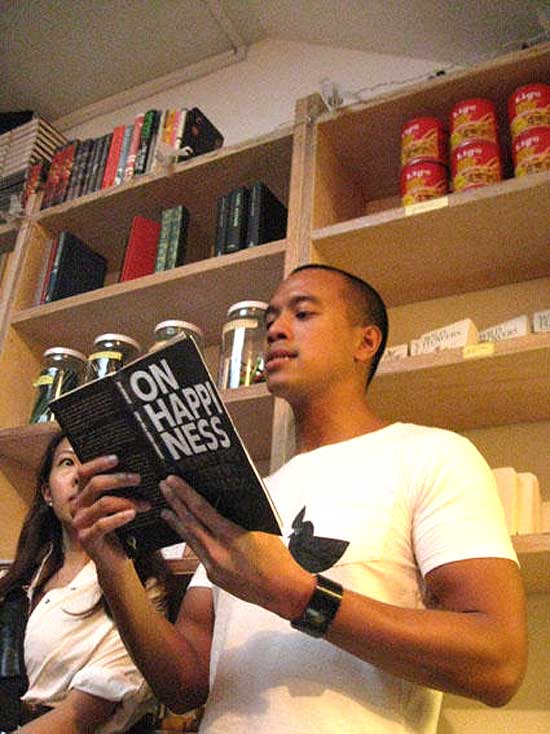

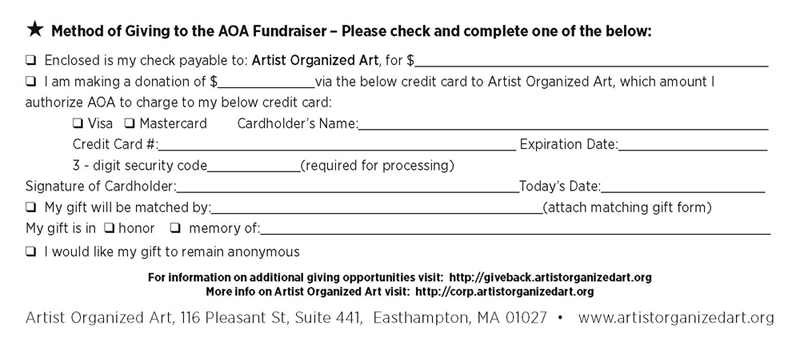

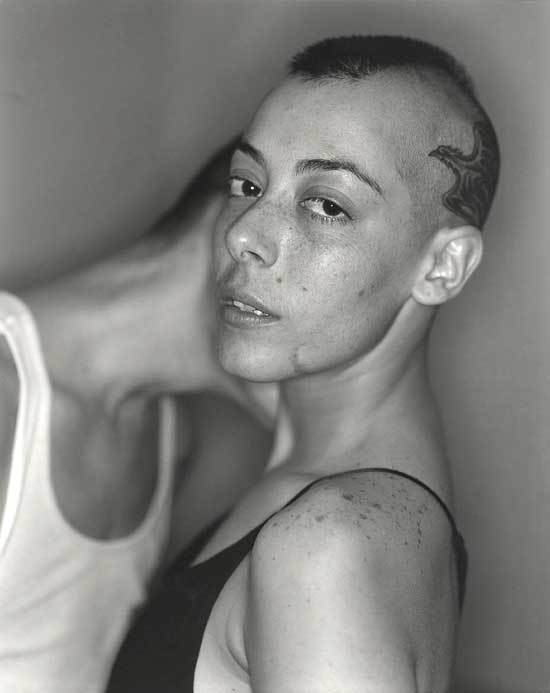

Brendon Fernandez in staged reading of ‘The Boxes’

For, it is not difficult to hear an echo of author in authority; as if the writer of the situation can play at being God—all-seeing, and in full control. The trouble with authority is that it is always already illegitimate. For, if something is legitimate, access to it would be open to everyone—governed by the Law. It is only when something is illegitimate that the authority of a person is required to enact it. For instance, a death-sentence can only be pardoned by the authority of the sovereign. In doing so (s)he is going against the legal system which sentenced that person to death; the same legal system that upholds her/ his very sovereignty. In other words, authority is the very undoing of the Law. To compound matters, any enactment of the law requires an executor of that law; in other words, a figure of authority. Hence, authority is both authored by the law, and its very author at the same moment—the hinge on which it operates, and also its very finitude. However, a foregrounding of its illegitimacy would not only shatter the illusion, but also bring about the collapse of the entire system. The very source of that authority though—of why someone has authority, and more than that why we grant authority to someone which necessitates our subjectification to that figure who only has the authority due to our self-subjectification—remains outside of reason, remains unknown; remains a secret.

In some way, the question that remains sounds paradoxical: if we posit the importance of protecting the secret (lest everything comes crumbling down), how can it be a secret if everyone already knows what the secret is?

Jo Tan & Rebecca Lee in staged reading of ‘The Boxes’

Here perhaps, we need to turn to the very notion of secrets themselves. And to do so, let us momentarily draw upon an old tale. When Isis poisoned Ra, she promised him the antidote in exchange for his secret name, which was the source of all his power. And when he whispered it into her heart, she felt herself filled with all the knowledge and wisdom of Ra; all the power that came with his name—Amen-Ra. However, it was not as if no one else knew it; one would have been hard-pressed to find someone who didn’t know the fact that he is Ra. What this shows is that secrets rarely lie in the content (after all, Amen is merely an affirmation), but in knowing that something is secret, in the gesture of acknowledging that the secret is a secret, that he is indeed Ra.

Perhaps this is the lesson of Andy Warhol. It was not so much the reproduction itself that is the art, but the very gesture of recognizing the objects to be reproduced. There is nothing to an old pair of shoes lying around; it was van Gogh’s realization of the possibilities in the singularity of the situation—those very shoes in that moment—that momentarily elevates it to the realm of art. In this sense, one can posit that both Warhol and van Gogh were authors at that moment of recognition: through their respective media, both of them create a singularity by arresting a particular moment in time. And since it is a singular moment, it is in some sense always also an original gesture; one that has never happened before, one that is also potentially non-repeatable. In this manner, one can posit that the artistic gesture is the reification of time itself: the concretization of a moment through a media, as if that moment was real; in other words, the authoring of a moment.

Audience peering through Png’s Plugs

The irony though, is that every gesture is always already a reproduced gesture. After all, regardless of media, one is capturing a moment, and more precisely, a moment that has passed. In this sense, all art is a reconstitution of memory. This is not to say that every act of memory is art; or that every attempt to capture memory is art. Far from it.

Perhaps here, one might consider the status of forgetting. Since forgetting happens to one, it is both strictly speaking exterior to one’s cognition, and also beyond one’s control. Hence, there is absolutely no reason to believe that each act of memory might not bring with it forgetting. By extension, there is no possibility of knowing if each act of remembering recalls the same memory. And it is precisely the impossibility of knowing—this unknowability that haunts all knowledge—that gives each situation the possibility of singularity. Hence, singularity is always already external to the subject; it is the very finitude of subjectivity.

This suggests that singularity, originality—or dare one say the artistic gesture—is found not in a completed, accomplished, work, but rather in the potential forgetting in that work. In this sense, art is the foregrounding of the possibility of forgetting. And since it is impossible to foreground what one cannot know, this suggests that art is always already in its praxis, and more than that, it is always already only to come.

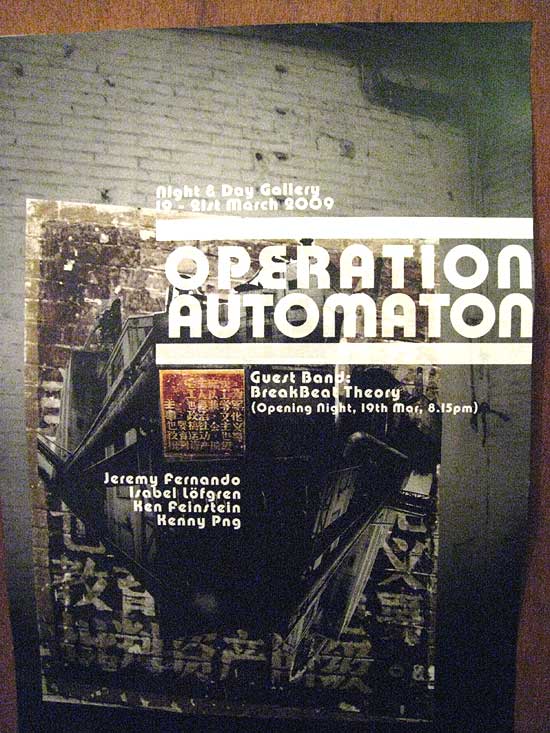

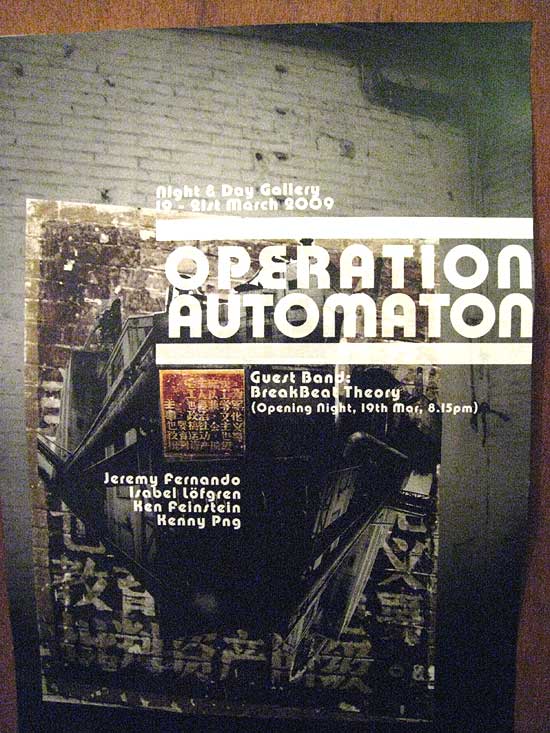

Poster for Operation Automaton

Night and Day Gallery: Singapore (19-21 March, 2009)

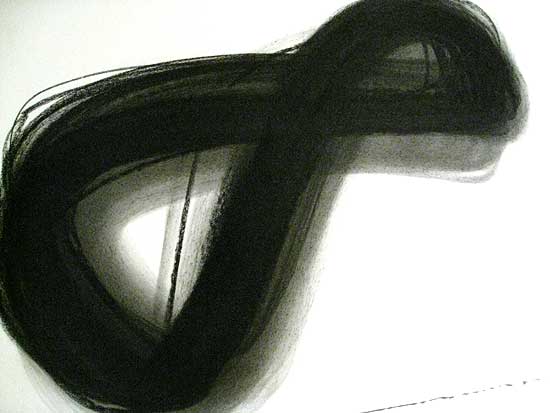

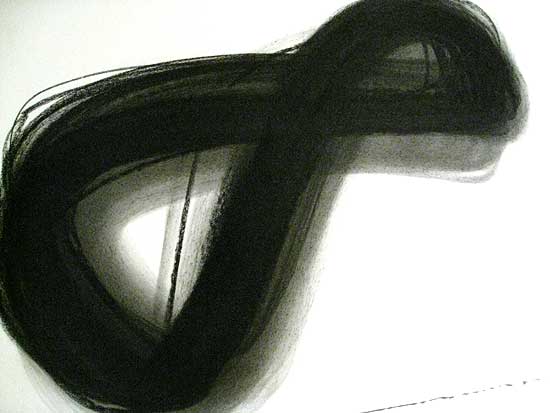

From 19 till 21 March 2009—about the same time as the controversy over Earnest—Isabel Löfgren, Kenneth Feinstein, Kenny Png, and Jeremy Fernando attempted to think the notion of art as praxis, think the relationality of art and the artist, through different media—sketchings (Löfgren), video (Feinstein), photography (Png), and painting (Fernando)—in an exhibition at Night & Day Gallery entitled ‘Operation Automaton.‘ Löfgren’s work involved the repeated drawing of a Möbius strip, until such point where the body automatically takes over, and cognition fades into the background. Feinstein’s repeated showing of train-tracks and public housing allowed the viewer to open the relationality between the two seemingly related, but yet unrelated, objects of everyday life. The individual photographs in Png’s piece were minute, and situated within electric-plugs: whomever wanted to catch a glimpse of them had to squint through the plug; calling into question the notion of seeing, and shifting the position of the viewer from neutral onlooker to active witness. And in Fernando’s piece, three blank canvasses were left next to headphones: people were free to paint whilst listening to the vastly different genres of music playing on the respective headphones. In various ways, not only did the exhibition foreground the viewer and the work in relation to art, it calls attention to the gap between the artist and the art itself.

This is an approach to art that acknowledges that part of art always lies outside the person; that at best can only be glimpsed momentarily. This is art in the precise sense of a craft at its highest level; where it consumes the practitioner, often in ways which are exterior to one’s cognitive ability. In this sense, art remains invisible to one; at best, it expresses itself through one.

If one can never be sure of the status of one’s act—whether it is reproduced through memory, or whether it is a new act due to a forgetting—every act is then both (n)either a first (n)or a reproduction. By extension, each time one performs an act, one is both neither a virgin and always already virginal. This is also a foregrounding of the illegitimacy of authority; one cannot legitimately say whether something is art or not. In other words, any judgement is based on nothing except the praxis of judging itself; where one cannot have any metaphysical comfort, or certainly, that one is correct (or wrong). Hence, art lies in its praxis, in each attempt at making something, doing something, practicing one’s craft; at best, all that can be said is that art is a gesture towards the possibility of art. More than that, whether something ever reaches the realm of art—a reproduction that is not just a reproduction—or remains just another reproduction—not that there is any logical difference between the two—always already remains a secret from us, perhaps until it happens. And when it does, its reason might still remain unknown to us; which means that all attempts to reproduce the gesture might always only remain a reproduction.

Kenny Png, ‘Plugs’

Mixed Media, Operation Automation

And on 23 July, 2010, it was this risk that Brendon Fernandez—who played Algernon Moncrieff in the Wild Rice production—along with Rebecca Lee and Jo Tan ran when they put on a staged reading of Png’s play ‘The Boxes’ at Books Actually.2 Even though every performance of a play is also its re-reading, and potential re-writing, what was unique about this occasion was not the absolute absence of the author from the rehearsal process (that is more than common), but the fact that Png was absent even as he was credited as the director of the said reading. To complicate matters, Png crafted both the soundtrack and video backdrop in a divorced setting from his actors (all of whom rehearsed separately as well). On 23 July, at 7.30pm—completely blind to the preparations of the others—they began. What was foregrounded was the primacy of the text, and the reading of the text: in the improvisation that was needed for the actors, music, and video, to speak to and with each other, Png, Lee, Tan, and Fernandez, had to be negotiating not only with the others, but also the text. Hence, it was a performance not just of ‘The Boxes’ but of reading itself; one that could never be sure of its status as reading, of whether it was a unique performance, or merely the re-uttering of the words that were printed in the book; one that highlighted the lack of grund in all reading, all performance, all attempts at art.

In other words, art is nothing more than a gesture. And more than that, since art always already remains potentially exterior to the person, there are no artists; there is only the possibility of the gesture.

One that is made in blindness to everything but the possibility of art itself.

Isabel Löfgren, ‘Mobius’

from Automated Sketchings, Operation Automaton

_____

Jeremy Fernando is the Jean Baudrillard Fellow at the European Graduate School. He works in the intersections of literature, philosophy, and the media; and is the author of Reflections on (T)error, Reading Blindly, and The Suicide Bomber; and her gift of death. Exploring different media has led him to film, music, and installation art; and his work has been exhibited in Vienna, Hong Kong, Seoul, and Singapore. He is the editor of the thematic magazine One Imperative, and is also a Research Fellow at the Centre for Liberal Arts and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University.

1 http://www.channelnewsasia.com/stories/entertainmentfeatures/view/414049/1/.html

2 Kenny Png. ‘The Boxes’ in Jeremy Fernando & Kenny Png. On Happiness. Singapore: Math Paper Press, 14-35.

Books Actually is an independent book store which can be found at 86A Club St, Singapore. The owners, Karen Wai and Kenny Leck, are renown both for supporting the local arts scene and, more importantly, for having impeccable taste when it comes to literature. (For more information please see http://booksactually.com/)

#permalink posted by Artist Organized Art: 9/14/10 08:00:55 AMMonday, June 21st, 2010

Creative Sparks – Brooklyn

Inside The Artist’s Studio

Ted Partin, San Francisco I, 2004

by Eva Mantell

Seeking creative sparks to flick at the doldrums. As always, I want to overdeliver the art goods as I’m defensive about the subject, particularly in front of a general audience. I start from the idea that you, at your core, suspect that most contemporary art is a con. Correct me if I’m wrong. I put in another idea — that you think the very best art is unattainable, practiced by only a few anointed ones, probably long dead, off limits to mortals. A secret practice whose essence can’t be cracked by the clumsy viewer. Whose talent is God-given. Somewhere in between the con and the holy is where I see the best contemporary art and I want to share it with you as directly as possible, and gather some creative sparks for myself in the process. If I bring you inside the artist’s studio you can observe this all firsthand. You’ll be able to see work informally, pinned to the walls, under consideration, unframed, in a jumble. You will be able to ask the artists anything you want. You’ll be able to get up close to art and see what, if anything, happens to you in the process.

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2006

The Creative Sparks tour, another in the depARTures series, takes off from the Arts Council of Princeton. I must say Route 1, the Turnpike and the Verrazano are looking good this morning. Free, clear and almost picturesque, the highways draw us straight to Gowanus, Brooklyn into the courtyard of the Old American Can Factory, and into a really choice parking spot, which frankly makes all seem right with the world. This could be a fine day. Our first meeting is with Diana Cooper, maker of improvised, energetic installations, and she greets us at the door to her studio in her personalized denim work apron. She gets right down to business and shares her project at Jerome Parker High School in Staten Island with us. Cooper remains open, amused and confident as she lets us in on the paradoxically bureaucratic process behind her loose and improvised installation piece: the paperwork, the budget, the haggling, the hours, the travel, including trips to Germany to work with the glass manufacturer, the stories about the teasing workman and the offhand comments made by the students themselves. The piece itself is decentralized, geometrically lumpy, made mostly from zigs and zags bisecting an almost chapel-like series of blue glass windows. Looking around the studio I see a line, in this project and in others: a line that is an energetic, protean little bugger. It can be two or three dimensional. It can turn, wrap around, radiate, droop, about face, streak. The line can mass, reproduce and in increments it builds systems, cities and odd worlds. Cooper has written about playing with that line: “doodling is, I think, an expression of the unconscious, it sometimes captures inner connections and becomes, in its way, a system. Conversely, we might think of some of the graphic systems we are familiar with as society’s unconscious doodling.”

Diana Cooper “Out of the Corner of My Eye,” 2009, 11 ft x 110 ft x 6 in

Wood, MDF, glass, acrylic, epoxy and Nida-Core

Permanent Installation, Jerome Parker Campus, Staten Island, NY

Cooper is a conscientious about her unconscious, and doodles her way into some lovely art situations. Materials like bits of plastic, tubes, pompoms and other stuff that seems just barely dimensional join the parade, accreting into installations that come to look almost like a kind of chunky expanded painting…as much as things project they remain hovering over the walls and floor, relating to the surface planes of paintings. Her colors are very stark and very organized: the high school installation is mainly blues; here in the studio is a wall of photography and ephemera that is mostly orange. Another project is pink and green. It’s a system where all elements are knowable, all colors are knowable. It’s like seeing the ingredients and what comes out of the oven simultaneously. I get the energy, play, connections, and the continuous act of keeping going.

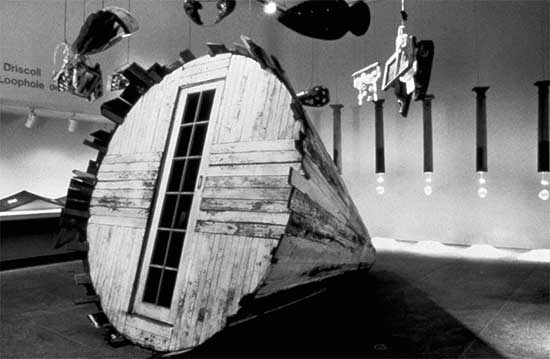

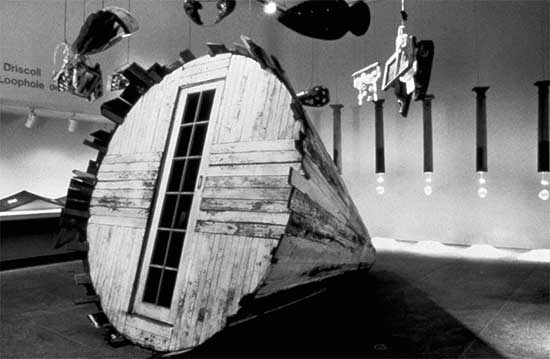

Ellen Driscoll “The Loophole of Retreat,” 1991

We walk upstairs and meet Ellen Driscoll, a ridiculously accomplished woman who chairs the sculpture department at RISD, and has permanent installations up and down the country, including one in the subway at Grand Central. I first saw her work in the ’80’s as a student, so I come to her as a fan, with great curiosity about how it all happens. She greets us with a curiosity about us too, how we live, what we teach, how our lives are put together. Her early works had a hand-made, hand-hewn, historic and literary feel that I have always loved. A linear quality with silhouettes as shadows in stereoscopic projections, with some chunky wooden parts, simple machines. 19th Century literature and history and tragedy. She connected through her process to another time, through piecework, through women’s work, through laborer’s work, to bring out narratives that might have been lost.

Ellen Driscoll “FastForwardFossil; Part 2,” 2009,

installation view, gathered water bottles, glue

In her studio today her realm is now the future, looking back on the present. The material is found plastic, discomforting and piquing. At ankle height are sections of a miniature dystopian landscape made entirely from those clouded plastic water jugs that Driscoll has collected in a kind of daily penitent’s tour of neighborhood garbage cans. The jugs, now transformed into surprisingly hard-edged geometric shapes, become child-like tableaus of the oil industry and a ravaged environment, with miniature derricks, scaffolds, fallen trees and toppled houses. The reclaimed plastic looks milky and translucent, appealing but perilously so as we know it embodies the story of fossil fuel pollution. The appealing playfulness of the piece combined with its finite message roils me.

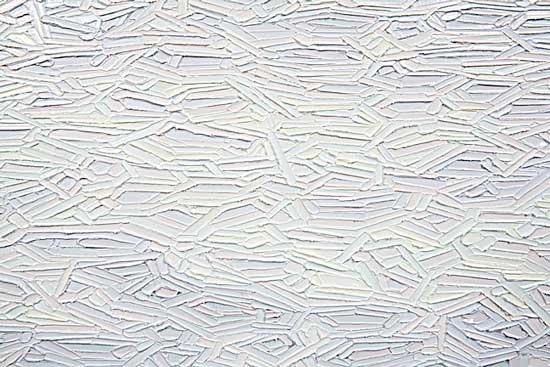

Stuart Elster “White Head,” 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

On the walls are drawings, in blue and black ink, with spills and stains, structures of industry, steel, stairways, memories of certain kinds of dead ends. She unrolls and unfolds walnut oil paintings, with spills and reactions, architectural and sweeping horizontal views of tortured landscapes. There’s a feeling of Romantic ruins, awkward, as I don’t know where to put the beauty and longing I feel in the overall picture of human failure. What to do? Document our failures? Find our place in it? Find our reason to keep going? Our meeting with Driscoll is surprisingly intimate, and it seems the larger questions raised are not going away any time soon.

Stuart Elster “White Head,” Detail, 2009, oil on canvas, 24” X 90”

Things can begin to look a little stark when the blood sugar drops, so maybe we better grab lunch. We go to Ici, on Dekalb, and the small restaurant we step down into, through the felt curtain, is organic, tasty, and seems to hit the spot (except I’m still hungry). As we drive to Long Island City to see Stuart Elster, I ought to eat the take-out muffins I ordered, but I get distracted, so they stay on the floor of the van in a white paper bag. Best to be a bit on edge.

Ted Partin, Bushwick I, 2009

Elster is devoted, intense, pleasantly on edge himself. His paintings are almost excruciatingly conceptual, to the point where I think they must be unphotographable, that’s how specific they are, how untranslatable from themselves they are. He has taken the humble copper penny as his subject, but his paintings depart quickly from coins, symbols or signs, though if directed by Elster I can see Abe Lincoln’s profile if I squint just right here or there. The paintings are about a painter painting paintings with paint. Think of Seurat, Ad Reinhardt and Jasper Johns with their eyes closed, their minds not being able to shut off making a painting. The practice of painting is offered up as microscopic moments of application, brushstrokes dissected, the rainbow stripped and exposed. Before us is paint, are colors, optics and a physicality so that each brushstroke’s highlights and shadows are scrutinizable too. A strange bonus, these works can be viewed with the lights on or with the lights off and they will perform for you either way. So naked are these canvasses in their conceptuality I think they are in need of an art critic to dress them in language and in theory! I look forward to a show of these works, and here’s hoping I’ll be able to understand the essay that goes with it.

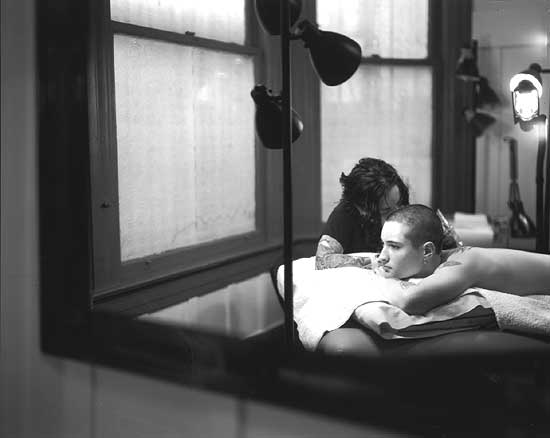

Ted Partin, San Francisco II, 2004

Down the hall we come to Ted Partin’s photography studio. Partin is earnest and open with us, spreading out the photos he has been printing. It’s rare to be near unframed, classic photographs, and to see their scale and sheen. Nothing digital here. In the quiet space of this kind of art (no surveillance cameras, no music, no soundtrack, no interaction) we can stare. Partin stages his large-format black and white portraits knowing that we expect them not to be staged, but as voyeurs, we’re happy to look either way. Here’s an anthropology museum of people and things to look at and then keep looking at. Ambiguity rules the day, as place, gender and ethnicities seem unknowable; as if, if we knew, we’d possess these people, these situations, fully. Their beauty and longing seems real enough. Their sense of themselves seems real enough. Stare away. In the meantime the world has changed. And changed again.

Eva Mantell

originated June 21, 2010

#permalink posted by Eva Mantell: 6/21/10 08:42:50 AMMonday, April 26th, 2010

The Rise of Art World 2.0 by Ted Mooney Two years into what we seem to have agreed, in full supine position, to call the Great Recession, it is clear to almost everyone that something has indeed taken its course, and that in many respected fields of endeavor things will never be the same. As someone who has pursued with equal commitment two parallel careers throughout my life─one in the art world (as an editor, a writer, and now as an educator at Yale’s graduate School of Art), and another in the literary world (as a novelist, essayist, and short-story writer)─I am struck, if not exactly surprised, by the similarity of the changes the recent financial meltdown has wrought on both fields, changes long in development but only now openly validated. I say changes, but in fact they are paradigm shifts, since both the art and literary worlds are undergoing transformations that will prove to be game-changingly radical. This much is certain: what was before, will be no more. The sooner we realize this, the more options we will have in the future.

Talking about this paradigm shift in regard to the art world is strangely difficult, for the very reason that the term “art world,” so casually bandied about by almost everyone, is most often used to refer to something that is at best a suspiciously convenient myth. No such all-encompassing art “world” exists. Most likely it is this misuse of the word “world” that has left the term “art world” itself open to such a wide range of misunderstandings. But in fact “art world” does have a very specific meaning, one quite different from the fuzzy globalist entity most often summoned up by those who use it so indiscriminately. Simply put, the art world consists of all those involved in the commission, creation, valuation, promotion, presentation, sale, criticism, documentation, and preservation of art. And with that established, many other matters grow a good deal clearer.

While we have always had artists in the U.S., for example, the American art world─one including all the elements listed above─is a much more recent development. Borrowing from the nomenclature of the software industry, I will call the U.S. art world’s earliest incarnation Art World 1.0 and locate its emergence somewhere in the mid- to late 1930s, when a number of forces came together in New York to create it. These forces included the sudden arrival here of European artists fleeing the onset of World War II; the convergence in New York of other European emigré artists who had moved to the U.S. much earlier but now joined their fellow exiles in the nascent art capital; and a similar movement of American artists away from the heartland to the growing artistic ferment in the East. In addition to these historical migrations, the federal Works Progress Administration, at that time the largest employer in the post-Depression U.S., provided substantial support for the arts, allowing, for example, Willem de Kooning (who had reached New York in 1927) to earn more than three times the salary of a typical Macy’s employee of the same period, all while painting public art works for which he was paid with federal dollars. What’s more, several other elements of the art world as I have defined it were already in place: among them Alfred Barr’s then artist-friendly MOMA, such prescient commissioners of art work as Peggy Guggenheim, a handful of important galleries, soon followed by art and culture periodicals like In the Tiger’s Eye, and View —enough of the necessary elements, anyway, to give critical mass to the first genuine U.S. art world.

Money was certainly made within this self-contained enclave, but not very much, and the institutions and collectors who acquired the art works emerging from these artists’ studios did so mainly out of their acute awareness that this was a historic moment, unprecedented in the U.S. Few if any of these collectors imagined that the works they were buying would in a very short time increase astronomically in monetary value, so speculation was a negligible factor. It was sufficient that enough money be circulated through the art scene to keep the artists alive and productive. And with only short periods of stasis, indirection or revolt, the New York art world evolved from that first iteration into what we know today, its characteristic elements continuously shifting in relative importance as the art eco-system grew in volume and self-confidence.

I will leave the reader to decide when exactly the art world’s incremental upgrades occurred─when 1.0 became 1.1, and so on─confining myself instead to a few obviously watershed moments. By the late 1940s and early ’50s, the Abstract Expressionists had became pop-cultural stars whom the average American saw in equal measure as perplexing oddities (“My kid could’ve done that”) and gratifying emblems of postwar American dominance (“Take that, Europe”). Indeed, they became such accepted emblems of a newly prosperous U.S. that the federal government (in the form of the U.S. Information Agency, now known to have functioned abroad as a propaganda arm of the C.I.A.) sent their works on extended worldwide tour as a potent psychological asset in waging the Cold War.

In the late 1950s and early ’60s another major change occurred, as the soul-baring feats of the Abstract Expressionists and their progeny gave way to the cool ironies of artists like Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Andy Warhol, and all those other artists so hastily lumped together by the media under the rubric of Pop art. I’ll call this moment the arrival of Art World 1.5, since, in my opinion, it brought us halfway to where we are now. With it came a shift in sensibility that suggested a new detachment of artist from artwork, one that allowed the expansion into that same ironic distance of the other art-world elements, those that till now had usually played a secondary role. The valuation, promotion, presentation, and sale of art began to take on more weight, and the normative practices in these areas showed signs of changing and evolving in ways till then unforeseeable.

Simultaneously, a new breed of collector emerged, exemplified by people like Robert Scull, who made his fortune from a Manhattan taxi fleet inherited from his father-in-law, had no real background in art and simply bought what he liked—in quantity. Pricing became more aggressive, promotion took on a glamour of its own, and the social aspect of the art world veered increasingly toward spectacle. Not only did this period mark the peak of postwar prosperity in this country, but it was also a genuinely thrilling time for U.S. art, one as innovative in its way as that ushered in by the Abstract Expressionists. What’s more─and here Warhol is the obvious example─the subject of much of this art wascommerce, money, glamour, and popular culture. So for the first time the economic elements of the art world were unapologetically accorded billing equal to the art and the artists themselves. And with this acceptance, the ethos that has brought us to our present pass was unequivocally established.

To be sure, there were those who worked in explicit rebellion against the overall commercial trend of the art world─the Conceptualists, the Earthwork artists, performance artists, and others─many of whom produced art that, though intended in part to be “uncollectable,” must be accounted major work by any standards. But the expansion and increasing commercialization of the art world─punctuated by the booms and busts intrinsic to any market-linked community─continued apace. Among the innovations that contributed to the art world’s rapid development from the 1960s on were the decreasing cost and consequent proliferation of color reproductions in art magazines, the rise of graduate art-school programs (which implicitly presented art as a solid career path, comparable to, say, dentistry, in the security it offered), the increasing acceptance of the nakedly commercial art fair as a legitimate forum for presenting art, the ascension of the artist super-stars of the 1980s, the exploding resale market for contemporary art at venerable auction houses, the construction boom for contemporary art museums as they became more and more widely perceived as tourist magnets that no respectable mid-sized municipality could do without, and, finally, the vastly accelerated exchange of ideas and images that the Internet allowed. By the time the Museum of Modern Art reopened its doors after its lavish renovations of 2002-04, it is safe to say that Art World 1.9 had reached its apotheosis and begun its ongoing decline. Art World 2.0, a complete reset of the original, with consequences only beginning to be known, was taking shape.

Why do I locate this changeover at that moment? It’s tempting to point to the example of the newly expanded MOMA, a grotesquely misconceived distortion of its former self. As far back as the 1970s there had been talk, both within the museum and outside it, of declaring MOMA a historical museum, a museum precisely of modernart, which is generally seen as having come to a triumphant end with Minimalism. Watching MOMA continue to show contemporary art in its ostentatiously corporate, quintessentially modernist quarters seems to many like watching a 75-year-old man (the Modern opened in 1929, the very year the Great Depression began) attempt a kickflip indy at the local skateboarding park─a sight unseemly at best, but in any case a clear indication that all self-awareness has long since departed the scene. That may sound like a cheap shot, but within it lies a kernel of ineradicable truth. Every three generations (and I’m using “generation” to mean the traditional 25 years, not the five to ten years implied by advertisements and over-wrought publicists) the living memory of how the world was “back then,” what its inhabitants at that time aspired to and how they went about getting it, begins to die off. The number of eyewitnesses rapidly diminishes until we become reliant on second-hand accounts, self-serving memoirs, and conflicting rumor to summon up a vision of the original. Soon nothing can be verified with certainty, the “real” past is lost, and it can only carry on as a simulacrum of itself. Not until then, paradoxically, can the genuinely new, brought into being of its own necessity, be born and thrive on its own terms. Now, for the American art world, that time is upon us.

While it must be emphasized that Art World 2.0 remains in its earliest stage of development, it currently seems characterized by a studious rejection, quiet but steely, of the corporatization of art so enthusiastically and profitably pursued during the Art World 1.9 years. Among my grad students and many of their confreres in their mid-thirties or younger, there is a strong preference for art that in one way or another emphasizes “secrecy,” subversion, withholding, ephemerality, word-of-mouth invitation, sub-visible presence, intimate one-on-one interaction between artist and “viewer” and strong artist-to-artist dialogue. Where there’s institutional critique (and there’s a lot of it) it’s unlikely to be cast in the flamboyantly confrontational style of, say, Hans Haacke. Instead it might take place within a chosen “major New York museum”─the default term proposed by some leading museums after the almost Talmudic deliberations of their legal departments─among a group of invited participants, the results to be documented, if at all, by the museum’s security cameras. (It seems significant in itself that “surveillance”—both inside museums and elsewhere–is a hot topic among Art World 2.0 artists, who are acutely aware of the demise of privacy and ingenious in their attempts to resuscitate it.)

In addition, widespread revelations about the recent criminal activities of respected banks and international corporations, crimes that have almost without exception gone unpunished, have made virtually all corporate practice suspect to a sizable proportion of Americans, and to many of the Art World 2.0 artists it is, at least for now, anathema. As they attempt to reclaim for artists the freedom and respect once naturally accorded the best art work, independent of the by-now customary financial indices and career-path signposts, they have begun to seek alternative ways of structuring their art world. And they have learned how to adapt for their own purposes the near-universal corporate response to the recent financial meltdown; they have developed ways to eliminate (or at least minimize) the middlemen.

This strategy is only possible because the old Art World, as well as modernism and the various morbid offshoots that followed its demise, is dead to them. They accept this as a fact, but don’t dwell on it, since the corporatization that marked Art World 1.9’s endgame is of little relevance to them, except as a warning. What most concerns these emerging Art World 2.0 artists from a practical standpoint is regaining control of how their work is presented and, given the ever-greater importance of the Internet, how the reproduced images of that work are disseminated. To those ends, many prefer to avoid long-term gallery affiliation altogether, seeking instead the most suitable venue for each new project as it is completed. By stringing together a series of one-shot appearances in places of their own choosing, they are better able to maximize their freedom and shape their work’s development. This may be seen as a direct response to the financial hysteria of the Art World 1.9 years, which led to the virtual extinction (though always with magnificent exceptions) of long-term, even life-long relationships between gallery and artist. In times not nearly as distant as they now seem, galleries saw it as their role to nurture and develop their artists, eventually to arrive at a mutually beneficial outcome through patience and hard work. But the frenetic financial pace of Art World 1.9─whereby new artists would typically be given two or three shows to demonstrate their financial viability before, if their work failed to sell impressively, being summarily dropped─did away with these nurturing relationships, and Art World 2.0 artists have quite sensibly concluded that their best option is to nurture themselves. This shift in thinking explains the primary emphasis Art World 2.0 artists place on building and maintaining their connections with other artists; they want a mutual support structure that they can depend on. Not only does this preference mirror their widely shared interest in reconnecting with their audience personally, in many cases on an intimate one-to-one basis, but underscores their deep-seated resistance to any form of outside control whatsoever, from any quarter. This insistence by Art World 2.0 artists on setting their own terms is yet another bit of bad news for galleries, who have already begun to see their high-end artists’ new work bypass them altogether, going straight from studio to auction house, where a successful sale can establish an artist’s financial worth much more effectively than a sold-out gallery show, which is by nature not at all transparent. The gallery dealer can and does make use of a whole range of tricks to achieve the desired public perception of a given show’s outcome, including under-the-table discounts, non-existent waiting lists for a particular artist’s work, failure to disclose the prices at which works really sold, and many other sleights of hand. At auction, the process is far more transparent: a work is sold to the highest bidder, conferring on the artist a more certain status and financial validation. Foreign collectors, especially from emerging markets such as Asia, are far more comfortable buying the work of an artist with whom they may not be familiar if that artist has already received the imprimatur of a respected auction house.

Obviously, auction houses are unlikely to accept a consignment from an untested artist, and that fact, along with the innate predisposition of Art World 2.0 artists to avoid entangling commercial alliances, assures that there will be many more artist-organized shows in the future. This polarization of sales venues corresponds, interestingly enough, to the drastically increased concentration of U.S. wealth into far fewer hands, beginning with Ronald Reagan’s election in 1980 and grossly accelerated during the Bush years. I have heard more than a few highly informed art-world players speculate pessimistically about the continued viability of art galleries in Art World 2.0. Personally, I think this is more a form of complaint than prognostication, but the possibility cannot be dismissed out of hand. At the very least it is a recognition, however indirect, that the reset implicit in the arrival of Art World 2.0 has already occurred.

What direction Art World 2.0 will eventually take cannot, of course, be known at this early date, but its initial aspirations are clear. Precisely because the monetary valuation of art, while based on some established indices, is at base irrational and subjective to the point of arbitrariness, the artist who is alert to these matters can work with a freedom unavailable to virtually all other workers in all other professions. This freedom was highly valued in the early stages of Art World 1.0─not only by artists but also by those composing the other necessary elements of the art world eco-system. Somewhere along the way, however, that freedom was lost to many artists as the art-world “support system” arrogated to itself more and more power, which came to influence artists themselves to an equally inflated degree. Those days may not be entirely over, but Art World 2.0 has arrived with the express intention of reclaiming its freedom and resisting outside influences, especially institutional ones, with all the energy and inventiveness its members can bring to bear.

They have already dismissed any notion of a master scenario for art’s development, simply by virtue of their arrival. They have the tools and weapons to take back their freedom, with its mix of blessings. Now we will see if they have the will. Copyright © 2010 by Ted Mooney

Author: Ted Mooney was a senior editor at Art in America magazine for more than 30 years and now teaches a graduate seminar at Yale University’s School of Art. He is also the author of

three award-winning novels, as well a number of essays and shorter works of fiction. His most recent novel, to be published by Alfred A. Knopf on May 11, 2010, is titled The Same River Twice. A video trailer for this book was created in collaboration with new-media artist John Gara and can be found at http://tiny.cc/TSRT-video.

#permalink posted by Ted Mooney: 4/26/10 12:24:54 PMThursday, March 25th, 2010

Mark Bloch at Emily Harvey Foundation

New York’s SoHo, 03-25-10

correspondence: in the Artists’ Voice

photography: Tom Warren for Mark Bloch

at Emily Harvey Foundation

The Art of Storàge

by Mark Bloch

Storàge is a new art form for our times in which artists will prevent at all costs, their work from seeing the light of day. Artists must conceal what they do, make sure no one finds out that they are brilliant. If an artist must show someone something they have created, they should show another artist so as not to upset the art markets. Other artists do not really count as human beings so there really is no harm in telling them. That is how art continues to thrive. Artists are sequestered from the rest of humanity. But one should proceed with caution because occasionally artists know actual people and the news of what kind of work the artists are producing must not spread to civilians.

Storàge is an art form like many others: collàge, assemblàge, frottàge. The accent is on the second syllable. The emphasis is on the storing of important information and objects–preferably one of a kind objects, although the storing of multiples is also encouraged–until a great deal of time has passed and the ideas and images contained therein, hidden from public view, have been discovered and explored by other, less talented individuals. This is bound to happen while the work is rotting under lock and key, no matter how advanced the work. Even the most vanguard artist will be unable to stave off the advancing future which will soon provide the unique conditions necessary for the artist’s work to be removed from Storàge without consequence.

Once a work of art has been rendered culturally feckless, Storàge is no longer necessary. The work can now be trotted out into the marketplace where it will no doubt have to endure other types of packaging, wrapping and covering which are part of the Storàge process when enacted by a Storàgist but in these new contexts the accent in Storàge is removed and it becomes simply storage in which excessive packaging and hygienic germ free protection is always considered good for business. Of course any work of art or other consumer item, no matter how processed and “valuable,” always remains in danger of being placed on dusty shelves in the forgotten back rooms of galleries or museums by art professionals. This is where the nuances of Storàge and storage are revealed–for it is these very art professionals who are uniquely qualified to determine whether or not an artist’s work is any good. During the interim period when the artists are left trying to make this crucial decision for themselves, their work must be safely hidden from view while these art professionals are courted at the artist’s expense without causing too much of a fuss, for it is the artist’s passion that must also remain in the limbo of Storàge, not just their output.

Sometimes fear of the art professionals will cause an insecure artist, one prone to alarmism and in constant dread of being accused of being labeled an exhibitionist, to send works into hiding early, thus risking beginning their career as a Storàge Artist prematurely. But there is nothing to be alarmed about here. Fears about these types of fear are only a waste of time. Any uncertainty at all must always be acted on immediately. To err on the side of invisibility is never a mistake. If an artist has any doubts at all about the worthiness of what has been created, they should simply place the work in a secure area, free from intellectually curious intruders where no one can see it. In fact experience has shown that no work is too ripe to entertain misgivings about its readiness for public consumption. Any suspicions at all should be indulged whole-heartedly and enthusiastically by the Storàge Artist.

Mark Bloch

More on The Art of Storage (.pdf)

The Art of Storage was recently seen as part of Mark Bloch’s one man show “Secrets of the Ancient 20th Century Gamers” at Emily Harvey Foundation in NYC March 18 through April 2.

#permalink posted by Artist Organized Art: 3/25/10 11:47:00 AMWednesday, March 10th, 2010

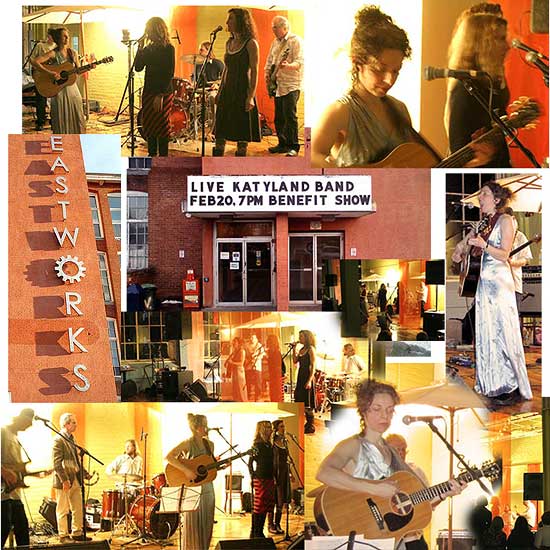

NEW WORKS • NEW VIEWS • NEW MINDS: Stage One: KATYLAND live at Artist Organized Art Benefit Launch

by Jessica Higgins and Erika Knerr

photography: Denis Luzuriaga

Participating artists: Aimee Xenou, Alicia Renadette, Andy Laties, Andrew Greto, Ann Lewis, Barbara Neulinger, Beth Lawrence, Carl Caivano, Christin Couture, Christine Tarantino, Christopher Blair, Dave Gloman, Dean Nimmer, John Landino, Denis Luzuriaga, Dwight Pogue, Erika Knerr, Fletcher Smith, Jessica Higgins, John Romanski, Joshua Selman, Kathleen Trestka, Katie Richardson, Katy Schneider, Laurie Goddard, Maggie Nowinski, Matt Anderson, Matt Anderson, Nancy Natale, Ninette Rothmüller, Pablo Yglesias, Rosa Guerra, Sarah Valeri, Sue Katz, Susannah Auferoth, Tracey Physioc Brockett, William Hosie, Luzuriaga video includes Ursonate Urchestra

February 20th was an auspicious date for the arts community! That Saturday night, was the first of three parties to benefit Artist Organized Art in which A.O.A. threw a community outreach event, arts network builder, exhibition, performance…did I forget to say fundraiser?

Northampton’s Katy Schneider, a guitarist, singer, songwriter and painter, accompanied by Julie Starr and Caitlin Bosco on back up vocals, Jason Smith on drums and Bruce Mandaro on guitar and mandolin. http://www.myspace.com/katyschneider. Also see Katy’s work at www.katyschneider.com

The event featured large projected images by local artists of the Pioneer Valley in Massachusetts and hard and soft indie music by Katyland along with some great cover songs, a regional progressive music favorite.

Denis Luzuriaga, a painter and video artist, compiled the projected images: in the dead of winter the crowd was treated to a colorful array of visual artworks, documents and pleasantly dated black and white photos of beach scenes.

le=”text-align: justify;”>The overall effect; “a swirling sound stretched out on the night with projections of art interfacing the viewers” Jessica Higgins

Each element of the event reflected a key component of the AOA mission to support creative independence in the form of self-supporting and self-generating exhibitions through artist organized media, events and cultural education.

The festivities took place at Eastworks a converted warehouse on the river at 116 Pleasant Street in Easthampton. Artists of all kinds and their allies came from neighboring towns as well as the studio and residential community of Eastworks, a loft building community founded by Will Bundy.

The social and experimental quality of the event recalled important artist communities associated with the avant-garde: Black Mountain College during the 1940s and 1950s, the Village and SoHo in the 1960s and 1970s, and California in the 1970s and 1980s. Why not Massachusetts as an internet hub brought together by AOA in the 2010s?

The event represents a significant group effort organized by artists: Susannah Auferoth, Jessica Higgins, Erika Knerr (also representing New Observations, the seminal New York arts magazine that was recently acquired by AOA), Denis Luzuriaga and Joshua Selman. Artist Organized Art is working to improve the quality of life through community culture.

The event isn’t over yet. If you were there and have pictures of the event, send them in to be a part of the record! If the event sounds like fun and you’re bummed you missed it, keep your eyes out for more. AOA is ever eventful.

The success of A.O.A. comes from community support (cultural, logistical and financial), which means everyone is invited to be apart of it, enriching our world by organizing its culture as artists. Benefit parties for Stage Two and Stage Three will be forthcoming.

#permalink posted by Erika Knerr: 3/10/10 08:16:00 PM