La Biennale Di Venezia Sante Scardillo posting from this year’s Venice Biennale

Cautionary note: this review is informed by the views and biases of its author and his practice as a militant artist in the past two decades. Every pretense of objectivity is purely casual.

This year is an “astral alignment” year: once in a decade, Venice Biennale, Kassel’s Dokumenta and Munster Skulptur Projekte, inaugurate at a few days lapse from each other, making it possible for the truly committed (or sycophantic, or both) to attend all three celebratory bashes, not to mention the Basel Art Fair, scheduled right in the middle. This is no easy feat, I must commend those who manage: it requires military-like planning and discipline, diplomatic skills and actual means and import: it is useless to go without the proper invitations, after the expense of travel, foraging and lodging, one will be left out of the gatherings that justify the trip.

Knowing my limits, I am only focusing on Venice, where I have some strengths: language and culture (I am a native Italian, raised and educated there) and a background, since begrudgingly, this is my third Venetian tour of duty. It is an amazing scene: if one is determined, one can go to the most incredible receptions and meet the most normally unapproachable people: a number of Museum directors and important collectors can be met in one night, that a working artist at the bottom of the feeding chain like I am, would otherwise meet in 20 years, if that. But the inevitable question, once one has proven a certain brilliancy in conversation, exhales from the mouth of the illustrious counterparts: “Do you have any work here?” and that is when the earth should open, since it is clear that in spite of all, the conversation will never bear tangible fruit. But this is the first year I really could not care less: I am 47 years old and the only reason I came here is that the Love of my life wanted to and I had a perfect alignment of travel and lodging circumstances: we got frequent flyers seats without a problem, in spite of calling for the first time 2 weeks before departure day; the friend who is our host in Venice will leave here in a year or so (this was our last chance to benefit from his generosity) and I know so many people involved in the show that it was not too difficult to sum up the invitations necessary to attend at least a few events and have a relatively free range. I hate the feeling of exclusion and that is why I would rather not go to these things than not be welcomed with open arms and this year, for the first time, I have noticed a real crackdown on people trying to get into parties and even in the show itself during the preview days, without having the proper paperwork of multiple invitations.

Should I really call them “crashers”? What’s the sense of making people travel all this way with an invitation, only to discover that they do not possess all the right types of invitations, that a card is missing and it was the one necessary to go to the cocktail-dinner-post dinner-whatever other occasion? But few things ever make sense in Venice, though the crumbling city holds a spell on all participants, bystanders and locals alike. It is the only place in the world where I get Stendhal Syndrome: it is a codified condition (by Italian Psychologists, of course) resulting, in certain individuals, in physical sickness

(think euphoria to the point of nausea) deriving from overexposure to art and beauty. After a week or so in Venice, I start feeling seasick, in spite of never travelling on boats. And the only way of curing the symptoms is to leave, at least for me. I guess one reason for the organizers to be more selective, is evident in the volume and “quality” of the crowd I encountered inside the shows and the parties: there are the denizens of the artworld, whom I know from New York, Italy, Paris, London and other places; but they are outnumbered 100:1 by those who clearly have more power, access, money, swagger, or whatever else it takes to be here than taste and appreciation for what the main reason to be here should be. The artworld is becoming a victim of its own success: as art becomes more palatable for the masses (in whatever aspect or form), the masses are pushing at the gate and filtering in, if not outright deluging.

It’s not a matter of being elitists, culture is so by its very definition, art even more so; and when the money starts coursing through the artworld at the ridiculous pace it has been lately, which makes the 80’s look like a period of somber moderation, it is inevitable that the Trump wannabees should find it a natural haven. It is just sombering to see this happening in the flesh and sad, when those who really have very little to do with art and culture, but are attracted to the buzz and glamour of the Biennale events, manage to have prelation on those who have no choice but being attracted. Nationalistic bias apart, it is universally recognized that Venice provides the most desired and clamoured for exposure of any other art event of its kind. And this is the reason why, outside of the anointment of officialdom, but with various formulas entitling them to use the Biennale Logo, all kinds of entities and individuals organize art events of the most diverse nature, hoping for at least a fraction of the public to see them. There are at least 100 parallel advertised shows and events this year, an absolutely impossible amount, especially given the geographic layout and transportation options the city offers. In all fairness it is impossible even to see in depth everything inside the two locations of the official show: it would take weeks, especially with the open floodgates of Chinese video art, a major onslaught this year.

Yang Fudong has a featurelength video broken up and projected in 5 large rooms coursing through the center of the immense (think ¼ of a mile long, 180 feet wide) main exhibition space, like a dark river. Like many other artists, once invited to the most desired vitrine for their work, he doesn’t seem to understand (or maybe deliberately ignores it) the demands it makes on the public, which will be stampeding through a show with hundreds of installations by different artists, all on the same monumental scale of a one person show in a major gallery or museum. It is, in my view, self defeating to count on work that doesn’t have an immediate and powerful visual impact to make an impression. Though it is understandable that given the (very possibly) once in a lifetime chance, many artists would tend to go overboard.

It is useful for the non completely schooled in the intricacy of this Byzantine art show to understand its curatorial dynamics. It started in the 1890’s as a vetrine for art of the turn of that century, still ruled by academia, which was in turn ruled by the rulers of the then “important” countries in the world, all but one, monarchies. Each was invited to build a pavillion in a newly developed area, the last (and newly developed) available dry land in Venice, and to staff and decorate (with the art of one or more prominent artists from that country) it every two years, to show the rest of the world what was important to it esthetically. Over the course of many years, the show has reached its present (and ever changing) formula: the ”Italia” Pavillion (the biggest by far) is the seat of the show that has come to represent the point of view of the organizers: a survey of whatever meaningful art is being produced at that time as seen through the eyes of a curator they chose for that specific edition. The show, too big to fit only in that location, traditionally overflows to the former seat of the Arsenal of the Venetian Republic, an industrial area of the XIV century (expanded as the fortunes of the Venetian Republic did throughout the XVII century), whose massive (think walled city) perimetral walls are not too far from the pavillions area inside the city park called “Giardini della Biennale”, complete with dry and wet basins and amazing, enormous industrial groundfloor spaces. The task befalls one curator (or more) that is carefully selected in order to maintain a balance in the artworld and has been, in the last 2 decades, not an Italian, as Italians are presumed guilty of making choices pandering to this or that local power, upsetting all others. A foreigner is (historically, as it happens, and in all of Italy) considered to be a less partial arbiter.

The chosen, this year is Robert Storr (formerly of New York MoMA) and I must, again begrudgingly say that there is something else that is new this year: the show is actually interesting in its apparent curatorial statement. Storr has chosen a line that celebrates the classics of the contemporary art scene, Ryman, Ellesworth Kelly, the recently deceased Sol Lewitt and many others of their caliber and relevance in the Italia pavillion. And continuing the streak of grateful tributes (and, it seems, of subtle criticism germane to the choice of the Cuban, dead gay Aids victim artist Felix Gonzales Torres to represent the United States of America in its pavillion, not curated by Storr: each government, through its official branches in the artworld. chooses a curator for its own pavillion). Storr’s exhibition (the survey of “Art in the Present Tense”), whose redundantly pompous title is not worth mentioning here (why not quit altogether with the insistence on naming a show that already carries the most revered name of any recurring show?), shows a solid, consistent curatorial vision. And one that I cannot refrain from lauding: in spite of seeing how popular the kind of work I have been making for decades has become in the past couple of years and how many people take credit for making “political” work now that it is fashionable, most of the work is weak and murky in its statements. But this is what I appreciated: Storr seems (to me) to be saying: in these dark times, if you want to say something criticizing power, you have to be shrewd, understated and circumspect, for fear of consequences; so, some of the “strongest” antiwar statements are obliquous<

/span> at best.

Emily Prince makes a gigantic map of the United States on the wall (25 X 120 feet roughly) using a fraction of the index cards on which she had drawn pencil portraits of “American Servicemen and Women who died in Afghanistan and Iraq, not including the wounded and Afghanis or Iraqis” (ongoing project since 2004), leaving most of them in archival boxes under a glass case, also part of the installation. Paolo Canevari, made a video called “Bouncing Skull” where a boy is juggling a soccer ball, but at closer inspection is the the object described in the title, the setting is the ruins of the United Nations Building in Belgrade, bombed in 1999. Even the boisterous Rainer Ganahl, unabashed in his condemnation of the Iraq war and the horror leading to and resulting from it in the last years 4 years, has been chosen for and invited to show work that predates that position and although challenging of the power structure, is much less disruptive. I still think that if a curator wants to make institutional and social critique, being more obvious (and using artists whose message is politically more obvious) is a better direction to take. But the message is interesting and I found a certain elegiac, forlorn continuity in the tribute to the bygone greats, as well as the timid contemporary: I see a timid appeal to our bygone (or by-going, bye bye going?) civil rights and liberties, which are becoming rapidly part of that same illustrious past that the demised greats of art may also symbolize.

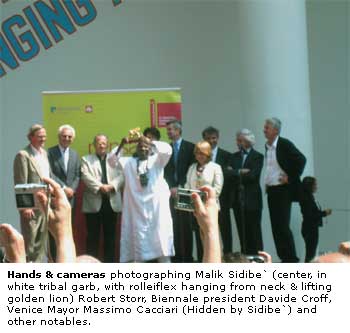

It is remarkable that what I read as a consistent, unrelenting, if not strong to my liking, critique of what America means today (especially under the global political profile) comes from the first ever American curator of a Venice Biennale. Everything seemed subtly political: even the choice to give the lifetime achievement Golden Lion prize to a 72 year old black muslim from Mali (one of the poorest nations in Africa, where he has been the village photographer for 6 decades) was a subtle and unimpugnable jab to the “market” way of understanding art, though one that the market will easily absorb into its way of going about itself.

There is also what seems as pandering to the “emerging” nations, in a coincidental meeting with emerging economies: Brasil and Argentina have a large presence in Storr’s show, with some of the best work. It was almost shoking to see Leon Ferrari’s Christ crucified on a 1;10 model of an F 111 fighter jet (Title of the 1965 sculpture, suspended from the ceiling: the Christian Western Civilization), after seeing it weekly in MALBA, Buenos Aires main contemporary art museum, all winter long. It is impossible not to wonder which market powers are going to benefit from these choices, as naturally the Biennale is a life and career changing event in the life of every single artist that is chosen to participate. China, aside from a pervading presence, also got its own “pavillion” (a fuel deposit inside an enormous XIX century industrial environment), whose most interesting features were the settings and what the artist Yin Xiuzhen did with them: an installation of life size, horizontally set dozens of mid-eval lances (think knight tournaments, with the two shining armors on horses clashing against each other’s multicolored lances. The multicolor schemes here are provided by old sweaters stretched around the objects they masterfully cover.) floating at different heights (starting at 30 feet) in a pervading manner. And outside, a gigantic air-conditioned igloo with a bunch of laptops on the Second Life website, purportedly showing a movie produced “there”. Africa also had what purported to be its own pavillion, though its concept was at best nebulous, its inclusion of Miguel Barcelo`, Jean Michel Basquiat and Andy Warhol at best dubiuos and its scope inscrutable, as well as the captions to its consistant video section. But it was also the one with the highest density of visually stimulating work, my favorite was a wall covered in small movie anouncements, called the best of the best.

Again, it isn’t clear what the promotional purposes of such choices where, but it was the most vital section of the show and the one that received the most plaudits in the very informal survey I conducted with colleagues, friends and other professionals of the field.

All this said, the most provoking things I have seen are at opposite ends of the scale: One, the result of an obviously genereous production budget, is a multiple video projection. The other, a couple of uninvited artists who worked in secret: a year ago, they buried under the gravel of the Giardini a bunch of round, relief signs made of cement all around the pavillions area (especially the American pavillion): The United Nations logo, a picture of the earth, the @ sign, a soccer ball and many others, loaded with meaning evident in the title of their piece: Symbols in the Dirt. On the day of the press opening, they went around with rake, shovel and wheel-barrel unburrinng them, tagging them with signs they brought along, unchallenged by the organizers, who did not want to regale them with the success de scandal that an arrest would have granted. Only to find the works gone by the next day: the personnel had been forced into unschedulled (and heavy duty) overtime, to dislodge each 200 pds cement pour from its unauthorized lodging. Staying in

the same geographical area, a plaudit also to the whimsical (and official) favela model built in front of the American pavillion (a scale model of the White House in yellow brick, how appropriate a corniche for Felix Gonzales Torres) by an invited collective of Brazilian artists staid on, providing a humorous counterpoint.

The title of the piece, Democrazy, I have had for years in my notes as a possible title for several pieces. These artists made me jealous: their ideas, I wish I had realized myself. I think it is the best compliment I could pay to a work of art.